For the last few weeks, I have been learning about how our aging population can positively affect education, particularly early childhood education. It has been an inspiring journey, one that has left me optimistic about our ability to structure scalable programs to meet dual needs.

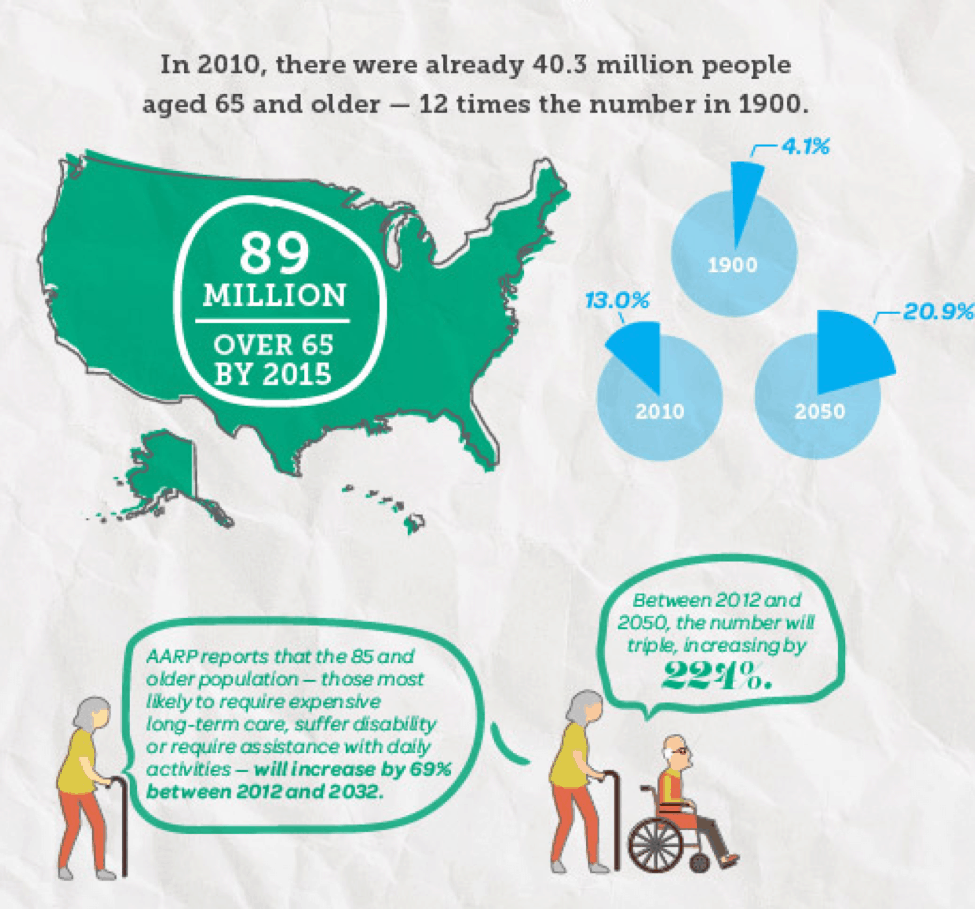

It is difficult to fully grasp the policy challenges our aging population presents. In 2010, more than 13 percent (40.3 million people) of the U.S. population were older than 65. That is 12 times the number in 1900. In 2050, more than 20 percent of the population is projected to be older than 65.

As one of the largest budget items in the federal and state budgets, programs supporting our older population have a profound macroeconomic impact on our communities. Without taking into account other programs geared towards older citizens, Social Security and Medicare alone are more than 40 percent of the federal budget.

In addition, the costs associated with healthcare for older citizens drive many of the pressures on our healthcare policy. The Milken Institute for Health at George Washington University created a useful infographic assessing the costs of aging.

As anyone who has cared for an elderly friend or family member can attest, the problem also has a significant effect on individual households. Working family members often must either elevate their productivity to afford support for their family members or must use discretionary time to provide care for relatives.

As a country and state, our strategy for addressing elder care issues is based on model that does not resonate with today’s values or work structure. We have created a structure built around giving older citizens allowances and then sending them on a spiral from productivity to dependency.

While the problem is substantial, we are unable to agree on how to change it, in part because we disagree on strategy, but in part because the problem has grown to a scale that we cannot fully comprehend.

At first glance, early childhood education seems to be a less daunting policy proposition. There is general agreement about its importance, but there are still major disagreements about who should bear the cost and how it should be structured and regulated. We stumble through early childhood education visions, restructuring and renaming programs with every change in executive leadership and create complexities that inhibit our goals.

The Opportunity

In January, The Atlantic published a story about a nursing home in Seattle that runs a pre-school. The program is also the subject of an upcoming documentary called Present Perfect.

With an average age of 92, Providence Mount St. Vincent’s (aka “the Mount”) population is older than the average retirement community, but it has nonetheless enacted a model that simultaneously serves the needs of two populations.

The Mount is not the first or the only intergenerational service program. A Washington-based group called Generations United researches, advocates, and shares information about how to establish “shared site” programs. Nationwide, Generations United estimates that there more than 300 sites across the country compared to a conservative estimate of 10,000 senior centers and more than 330,000 licensed child care programs.

These programs come in all shapes and sizes. Some simply provide volunteer opportunities for adults in nursing home facilities. Others provide a more fully integrated curriculum for the two groups.

Studies of this work exist but are not widespread. A recent study of a similar program in Baltimore showed that K-3 students working with older adult volunteers improved reading performance and improved classroom behavior.

Generations United has an easy-to-read report that demonstrates a broad list of results of inter-generational programs. Here are a few of the most compelling results:

- Preschool children involved in intergenerational programs had higher personal/social developmental scores (by 11 months) than preschool children involved in non-intergenerational programs.

- Children who regularly participate with older adults in a shared site program at a nursing home have enhanced perceptions of older adults, persons with disabilities and nursing homes in general.

- In schools where older adults were a regular fixture (volunteers working 15 hours per week), children had improved reading scores and fewer behavioral problems than their peers at other schools.

- Older adults who regularly volunteered with children burned 20 percent more calories per week, experienced fewer falls, were less reliant on canes, and performed better than peers on a memory test.

- Older adults with dementia or other cognitive impairments experienced more positive affect during interactions with children than they did during non-intergenerational activities.

- Intergenerational programs seemed to have a lasting positive effect on participants that carried over to their non-intergenerational activities

As we finish round two of the state budget cycle and watch a seemingly endless volley of national political headlines, it is refreshing to see an idea that makes sense. There is something distinctively appealing about this kind of two-for-one approach to policy-solving. We have an agreed upon demand for more resources in early education and a growing supply of experienced adults.

According to Generations United, there are a handful of intergenerational programs doing good work in North Carolina. We need to find ways to build more, to connect these two policy issues, and to improve the outcomes for both ends of our population.

Weekly Insight Education