As a former employee of the NC Department of State Treasurer, the agency that oversees retirement and health benefits for public employees in North Carolina, I have a professional and personal interest in retirement and benefit policy. I was closely watching the N.C. Senate earlier this week, as the Committee on Pension and Retirement and Age debated Senate Bill 467.

As introduced, the bill would end government pensions and retiree health benefits for future state employees, including public school teachers. It would not affect current employees or retirees. Instead, the bill would steer new employees into a 401(k)-style plan in lieu of providing a pension benefit. Additionally, it would eliminate the state’s provision of health insurance for employees in retirement.

The News and Observer and U.S. News have covered the debate, which has been going on in North Carolina and across the nation for many years. For an in-depth look at the issue, see the Center’s 2015 research by John Quinterno: Public Price of Growing Old.

A tough issue

The debate about retirement and health benefits is complex. No, really. There are a lot of complex public policy issues, but these are exceptional for two reasons.

First, the scale and impact of public benefits are large. In most counties, the school system and units of local government (municipal and county) are among the largest employers, so the issue directly affects a lot of people. Of the 10 million people in North Carolina, approximately one in 10 is a retired or active public employee. This means that there a lot of interested stakeholders—a sure-fire ingredient for complexity.

Second, the principles driving the debate are difficult to understand. As economist George Stigler once wrote, “The public has chosen to speak and vote on economic problems, so the only open question is how intelligently it speaks and votes.”

Generally speaking, retirement issues involve macroeconomic principles that make it difficult to compare with individual or business experiences. States and local governments have fundamentally different perspectives than individual or corporate enterprises. Well-managed states can think in 50 and 100-year increments. This long-term perspective leads to different credit and debt outlooks and has led to the creation of separate set of accounting standards for governments, the rules and principles of which are often foreign to people outside of government.

In addition, pension and benefit accounting is based on actuarial and accounting knowledge beyond that of most policy professionals and decision-makers, much less the general public. I say this having been one of those policy professionals who struggled to follow the actuarial forecasts and accounting rules that underlie these policies. There is a staggeringly small number of people in the state who fully comprehend the models around which pension assumptions and policy recommendations are based.

Reframing retirement

This complexity is compounded by the emergence of some fundamental shifts in how we think about retirement.

A 2016 study by Wells Fargo showed millennials have a different retirement outlook than baby boomers. Approximately two-thirds of millennials studied believe that retirees should be responsible for their own financial support. 74 percent did not expect for Social Security to be available to them. About 50 percent of millennials expect to help their parents in retirement, while only a quarter of baby boomers have done so.

As the General Assembly continues to debate the issue, here are three ideological frames to that need to shift as we build a retirement policy for the next era:

1. Retirement does not mean disconnecting from productive, purposeful life

Studies on aging show that maintaining purpose in later years is a strong predictor of individual health and wellness. For the last 70 years, we have largely maintained a notion that one’s productive life has an ending point and that people then enter a phase of post-employment decline until death. This model no longer rings true. Citizens’ abilities to be productive at 70 may be different than they were at 40, but the notion that we reach a point of disengagement from productivity is wrong and is, according to the studies, hurting us.

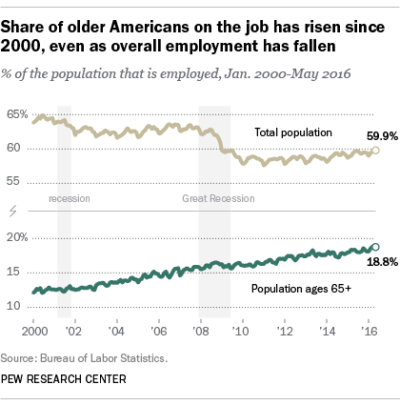

A 2016 report from the Pew Research Center shows that official employment among older Americans is rising. We need to pay attention to this change; we need to rethink strictures around when people start to disengage from the workforce; and we need to create structures that facilitate making citizens’ waning years purposeful and productive.

2. Universal retirement parameters don’t make sense

As life expectancy and quality of life in advanced years increase, it becomes increasingly difficult to set a standard age at which all people should shift how they engage with work. For some people, physical and mental capacity will last into their 80s and beyond. For others, deterioration begins earlier. We need to acknowledge these differences and work to develop post-employment benefits structures that account for them.

Similarly, not all jobs are the same and will lead to the same advanced age plan. Physically intensive jobs may lead to shorter work spans, while others may allow for a longer work life. As we shift into an economy where workers are less focused on singular careers and more focused on moving between jobs and occupations, we need to stop thinking about work as a terminal proposition. Work, or at least productivity, is a lifelong experience that can and should last well into advanced years.

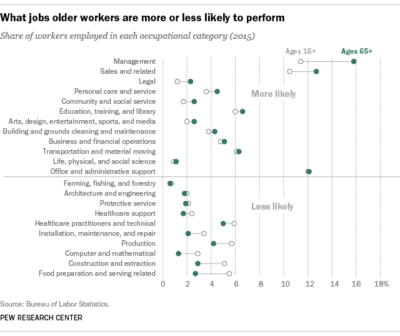

This Bureau of Labor Statistics data presented by the Pew Research Center, shows occupational categories where workers are working longer.

3. Oversimplification hurts the debate

Due to the complexity of the issue, it is easy to oversimplify the discussion of the issues and create red herrings. Here are a couple of the most egregious oversimplifications to be mindful of during the debate:

North Carolina and most states are not facing imminent bankruptcy concerns due to pension or benefit liabilities. It is wise to discuss unsustainable trends and to consider changes in the policy course, but it is not accurate to frame it in terms of bankruptcy.

The state is not facing a pension and benefits challenge due to a single issue or actor. Fees for investment managers may be an issue worth discussing, but Wall Street fees have not created the current retirement paradigm.

At the end of the day, the biggest player in the pension and health benefit space is the General Assembly. Legislators annually make the decision about how much to pay out in pension obligations. Unlike many states, the North Carolina General Assembly has been conservative in making obligations and has honored the obligations it has made. As such, it is wise for them to continue to discuss and debate this issue. Stay tuned as Senate Bill 467 moves through the Senate. This is a policy debate that we need to have.

Weekly Insight Aging