In the mid-1960s, North Carolina Governor Dan Moore introduced an idea he called “total development.” It was a grand, rhetorical frame that was at the same time omnibus and finite. He defined it as “improving, to the highest degree possible, every aspect of life in our state. It means providing better schools and colleges for our people to prepare them for jobs and careers; adequate, safer roads and highways to get them to school, to work, to church, or to leisure-time activities; better hospitals and other basic services to protect their physical and mental well-being; better opportunities for cultural advancement.”

Governor Moore went on to tie the idea to civic responsibility and explicitly charged citizens to play a role:

“[Total development] means across-the-board improvement in opportunities for all North Carolinians to develop and use their talents to the best of their ability–to enjoy useful and productive lives”

“Total development depends on you. Think about that. And think about questions like these:

Is your community working for its own total development?

Are you encouraging your young people to become educated and trained for better opportunities?

Are you fully aware of the educational resources of your community? Are you proud of your schools? Are you working to improve them?

Are you trying to improve your hospitals?

Are you encouraging the development of libraries, cultural programs, parks and historic sites and recreation facilities in your community?”

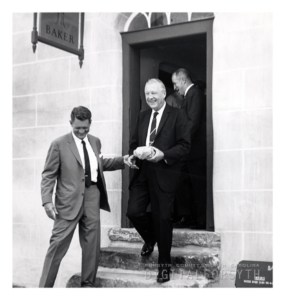

Truth be told, I did not know much about Governor Moore until earlier this week when I had the good fortune to spend some time with former N.C. Supreme Court Justice and retired Campbell Law School dean Bill Whichard. We talked about the strengths and opportunities for North Carolina, including the continued path to economic development, and he suggested that I look into the work of former Governor Moore who served as Governor from 1965-1969. Justice Whichard specifically pointed me to the total development idea. I was impressed by it and by the Governor who promoted it.

Full disclosure: I was a history major. As such, I may have an above-average enthusiasm in pulling out old volumes of political speeches. For those less inclined to do so, let me share four reflections and lessons from Governor Moore as taken from his collection of speeches and public papers.

A big frame, an action plan and an end goal

The political process is at its best when politicians frame a big idea and demonstrate a plan of action that includes an end goal. In recent history, political communication seems to have shifted on both sides to be more observational and less action-oriented. As a friend recently observed, there are a lot of homilies in politics these days–statements that are big on framing and goals and light on action.

Beginning on May 2, 1966, Governor Moore held a series of meetings across North Carolina over four days to talk about the total development idea. Reading his speech on the idea, the clarity of the framing struck me.

With the frame introduced, Moore went on to analyze the State’s productivity in agriculture, transportation, tourism, manufacturing and education. He cited clear statistics showing the state’s status in these areas and laid out specific work that needed to be done. He ended with a clear statement of goals for North Carolinians: to enjoy useful and productive lives.

I did not begin reading the speech expecting a juxtaposition with the present, but I finished feeling clearer about Governor Moore’s goals and priorities than I often am with contemporary politicians.

The power of you

Governor Moore concluded his total development speech with a directive to his audience. He encouraged them to find their stake in the process.

Contemporary politicians do not seem to speak directly to their audience as much. Reading over recent political speeches from both parties, there is a lot of “we” and not much “you.” I do not know whether that is a function of rhetorical trends, the era of politics, or the personality of the speaker. After all, one of the 1960’s most famous lines, John F. Kennedy’s call to public service, is a directive: “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.”

Governor Moore’s questions to the audience were an effective way to instill ownership in his speech and his priorities. From a rhetorical point of view, the questions provided an overview of his priority areas and reinforced them as a conclusion. More importantly, however, it challenged me, 50 years later, to think about what I am doing to affect my community. Too often, we have left it to experts, institutions and the unnamed “them” to affect our public lives and communities. Moore challenged his listeners directly and gave them ownership in the goals he was ascribing.

That sort of direction can be empowering and can lead people to greater, deeper action.

New era, old problems

Reading through Governor Moore’s speeches and papers, it was almost eerie how consistent our problems and opportunities are with what the state was facing 50 years ago. Governor Moore, for example, launched a significant initiative to improve infrastructure, particularly roads. Some of Moore’s frames and challenges around education, health, technology and growth could have been part of a 2012 or 2016 platform for either party.

The timeless nature of his words are reassuring and give hope that by studying the lessons from our past we may inform the strategies for our future.

However, my time with the Moore papers did highlight an indirect concern. I was able to conduct this research relatively quickly and easily because there is a collection of Governor Moore’s public papers and speeches that was published by the State Archives. The last similarly published set of papers was following Governor Hunt’s fourth term, which end in the beginning of 2000, meaning 16 years and the terms of three governors have passed without collecting the public papers.

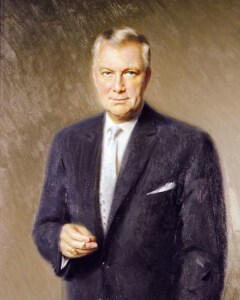

Funding for the archiving of gubernatorial papers, and portraits for that matter, has not been available in recent years. In the grand scheme of priorities, history and archives may seem like a luxury item, but our ability to write and learn from our history is part of what makes our civilization possible. If failing to learn from history dooms us to repeat it, what does it mean when our inability to record history prevents us from learning?

Focused agenda

The organization and focus in Moore’s speeches are unusual in state and federal politics today. Some of that may have been personality driven, but I wonder whether some of it was a function of the one-term limit on North Carolina Governors. Until the N.C. Constitution was amended in 1971, N.C. Governors could only serve one, four-year term.

From his inaugural address to his various legislative speeches, Moore was clear and consistent on his talking points and made it easy for a listener/reader to see his focus and understand what he was about.

Term limits are complicated. On one hand, governing has a steep learning curve. Over time politicians gain experience, which breeds wisdom and perspective on how to tackle problems. Furthermore, many policies require incremental changes and crossover executive election cycles. Consistency in leadership can provide stability to the policy process, reduce complexity, and lead to more straightforward results.

On the other hand, many public leaders may outstay their energy and enthusiasm and continue public service out of habit rather than out of passion. Reading through Governor Moore’s speeches, I came to appreciate that a fixed term limit forces a politician to focus on legacy and accomplishments from day one.

It is easy to feel like each generation is forging its own path, but the cycles of history overlap more than we realize. Sometimes connecting with previous cycles can ground us, inspire us, and help us reposition our footing on the shoulders that we stand on.

Weekly Insight Governor State Government