Any time the executive editor of the conservative National Review publishes a guest column in the New York Times, I pay attention. Those pieces are the equivalent of a policy olive branch and usually signal an idea that has bipartisan merit. Last week, Reihan Salam co-authored such a column with Rob Richie, the executive director at Fairvote.org. The column makes the case for a type of Congressional apportionment that involves larger districts that elect multiple representatives.

The main point is compelling: despite all of the debate about redistricting, simply redrawing the lines will not solve the problems with our electoral system and our current hyper-partisan Congress. The problem is more fundamental. We have sorted ourselves within and between states in ways that cannot simply be solved by redrawing intrastate lines.

To use Texas journalist Bill Bishop’s frame, we have sorted ourselves to live near others who share common interests. Unless something fundamental happens in Charlotte or Greensboro, those city districts will continue to be strongly Democratic and the suburban and exurban periphery will continue to be Republican. Nationally, states like Massachusetts will continue to be blue states despite, as the New York Times piece points out, having more Trump voters in 2016 than 16 other states. The result is a system where 98 percent of House incumbents were reelected, and where 402 of 435 House races were won by 10 percent or more of the vote (i.e., a landslide).

In many jurisdictions electoral competition is limited to primary elections, which means that candidates are incentivized to appeal ideological core of the two political extremes at the expense of moderate, middle-ground voters. For more background on the problem statement, read here and here.

A Proposed Solution

The solution proposed by Salam and Richie is to increase the size of voting districts and to allow for multiple winners from each district. Voters then rank candidates and indicate the order of their choices on the ballot. There is no limit to how many they many rank, and ranking all of the potential candidates never hurts the preferred candidates.

I found it is easier to understand the system by working through examples rather than describing it in narrative form. The video below was composed by Minnesota Public Radio and clearly describes the system.

In addition, the following is an example taken from Fairvote.org, which provides an example in narrative and chart forms. “Six candidates are running for three seats in a hypothetical district with 1,000 voters. Candidates Perez, Chan, and Jackson are Democrats, while candidates Lorenzo, Murphy, and Smith are Republicans. The district is majority Democratic; the Democratic candidates collectively earn 60% of first choices. However, there are a substantial number of voters who prefer the Republicans.”

“In this simulation, Jackson is the most mainstream Democratic candidate, while Perez and Chan have support among Democrats, Independents, and even some Republicans. Similarly, Murphy and Smith are both mainstream Republicans, while Lorenzo has support among Republicans, Independents, and some Democrats.”

“With 1,000 voters, the election threshold is 250 votes (25% of 1,000).”

Virginia Congressman Don Beyer has introduced a bill in the U.S. House, House Bill 3057, that would apply the approach nationwide.

Multi-Winner Approach in N.C.

The current momentum around multi-winner voting is focused at the Congressional level. Advocates recommend state-based, nonpartisan voting commissions to determine how the multi-winner districts look.

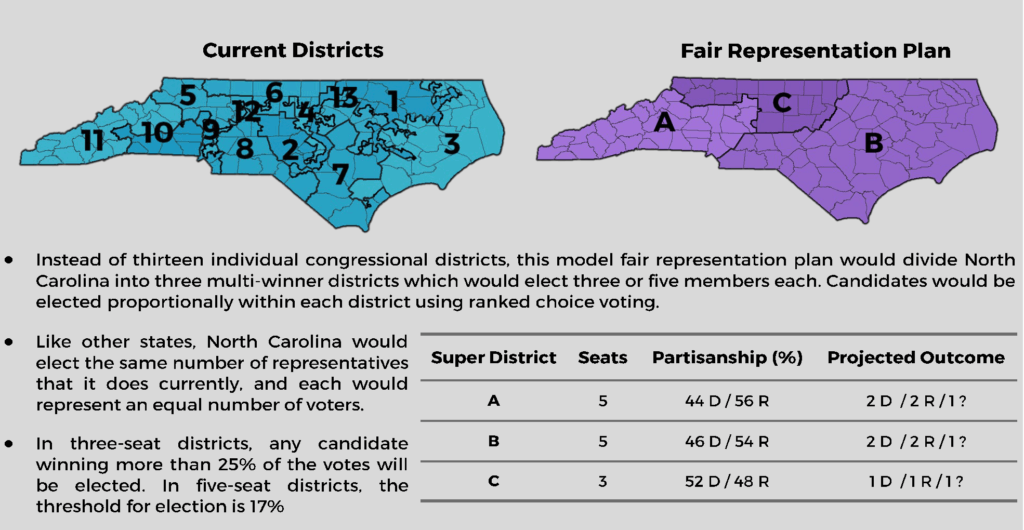

Fairvote.org has modeled a sample map for each state. The selection of maps can be found here. Below is their model for North Carolina.

One of the multi-winner system’s greatest advantages is the ability to construct voting districts that more closely mirror North Carolina’s current geographic and demographic patterns. This model is useful for illustration purposes, but it does not effectively capture the State’s regional identities. For example, it cuts Wake County in half, which creates potential overrepresentation for Triangle area interests.

I have not spent any time with redistricting software, but based on regional population dynamics, it is easy to imagine a state with Congressional voting districts that loosely comported within four to six economic development regions. Loosely stated, the new regional apportionment for North Carolina’s existing 13 congressional seats might look like this:

| Six region model | Five region model | Four region model | |||

| Charlotte region | 2-3 | Charlotte region | 2-3 | Triad/Northwest | 3 |

| Triangle region | 2-3 | Triangle region | 2-3 | Charlotte/Southwest | 4 |

| Triad region | 2-3 | Triad region | 2-3 | Triangle/Sandhills | 3 |

| East region | 1-2 | East region | 2-3 | East | 3 |

| Southeast region | 1-2 | West region | 2-3 | ||

| West region | 1-2 | ||||

If the approach proved successful for Congressional elections, it could also be a viable option for state legislative, judicial and local elections.

Things to Consider

The multi-winner approach has some compelling aspects, but there three potential weaknesses to monitor.

First, the system is complicated. To fully grasp the mechanics of the multi-winner approach, I had to watch two videos and read through two written tutorials. If a system like this is widely adopted, there will need to be significant voter education efforts. Additionally, we are at a point where faith in the electoral process is low: concerns about Russian interference for Democrats and concerns about voter fraud caused by lack of identification for Republicans. It is hard to imagine a shift to a more complicated voting structure not causing some consternation.

Second, voting in multi-winner districts requires voters to know about more candidates. Implied in the system is that voters will take the time to make informed choices and be capable of evaluating and prioritizing their choices around as many as five candidates. That requires more due diligence and voter engagement.

Finally, multi-winner districts create larger constituent bases for elected officials, which creates two significant changes to the status quo. From a purely representational point of view, larger constituent bases could affect constituent services and citizens’ abilities to connect with their elected officials. In addition, a larger base would likely increase the costs for each candidate to communicate with his or her constituents. One could argue about whether that is a good or a bad thing, but it would increase a potential barrier to entry.

Overall, as North Carolina continues to struggle with questions of redistricting, it makes sense to question some of the fundamental structures and assumptions of our current system. Like with any redistricting effort in this state, a move towards a new, more even system requires a short-term sacrifice for the Republican leadership. The question is whether Democrats can frame the longer term gains of a more competitive system in a way that suggests a shared sacrifice.

Weekly Insight Voting & Elections