In December, a winter storm dropped up to nine inches of snow in some parts of Wake County, causing schools to close and stay closed long after the snow had melted in some parts of the county. Due to the size of the district — Wake is the 15th largest district in the nation — a risk for black ice in one corner of the county can prevent the entire district from returning to school even once the snow has melted in another corner of the county. Between hurricanes and winter storms, Wake County students have had seven days off so far this school year.

Frustrations with school closures due to inclement weather have caused some to suggest breaking up the district, which would allow students to be closer to their schools and transportation decisions to be made on a more local level. In a recent column, John Hood, president of the John William Pope Foundation, argues that having multiple school districts within one metropolitan area would increase competition, thereby increasing school quality. Hood says that parents want “smaller, more manageable” school districts and have begun “opting instead for chartered public schools (each of which has its own governance board) or private alternatives” in the absence of policy change.

Critics of deconsolidation say it would be a step in the wrong direction, leading to the resegregation of schools along the lines of segregated housing patterns in the county. Opponents also argue that breaking up districts could lead to inequities in resources between districts as the tax base of smaller districts may vary drastically. Further, some argue smaller districts may diminish the benefits ushered in by economies of scale that allow centralized systems — such as food services, transportation, and maintenance — to operate more efficiently. In response to the idea of splitting up Wake County into smaller districts, the school system posted a series of Tweets describing the benefits of a consolidated school system and citing reporting on the resegregation of schools by Nikole Hannah-Jones.

So, what does the research have to say about all of this? First, take a look at how North Carolina got here and what the numbers are.

A look back

Starting in the 1870s, cities and towns in North Carolina requested authority to create special chartered school districts separate from the county school districts. Between 1870 and 1957, 74 of these special school districts were created, giving North Carolina a total of 174 districts.

This trend reversed in 1960 following the Brown v. Board of Education decision when the Charlotte City System merged with the Mecklenburg County System. The merger came at the recommendation of the Institute of Government at UNC-Chapel Hill, which said that consolidation would create several advantages, including “equal educational opportunities for all children.”

In 1976, Wake County did the same by consolidating and integrating Raleigh City Schools, which served far more students of color, with Wake County Public Schools. In Durham County, the story was the same — albeit a decade and a half later — when Durham City and Durham County public schools consolidated in 1992.

Since 1957, no new districts have been created in North Carolina. Since 2004, there have been 115 school districts in North Carolina — 100 of which are county school units, and 15 of which are city school units.

By the numbers

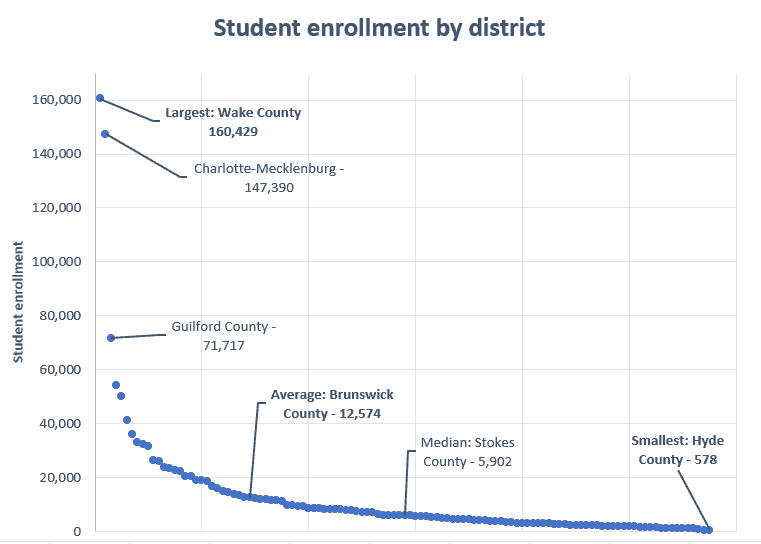

Student enrollment in North Carolina’s 115 public school districts ranges widely, as do the size of the 100 counties in which they are located. As of the 2017-18 school year, the smallest district is Hyde County, serving 578 students, and the largest is Wake County, serving 160,429 students.

According to a recent analysis by Governing, public school districts nationwide had an average enrollment of almost 3,700 students in the 2013-14 school year. By comparison, the average school district in North Carolina has about 12,500 students, close in size to Brunswick County Schools. Two of North Carolina’s districts — Wake County and Charlotte-Mecklenburg — rank in the top 20 largest school districts in the country as of 2014.

Nationally, the trend in amount of school districts since 1940 has been towards consolidation. In the 1939-40 school year, there were over 117,000 districts nationwide. By 1959-60 there were only 40,520, and in 2013-14 there were just 13,491. North Carolina’s 115 districts ranks it under the national median of 180 districts, found in Georgia.

Who makes the decision?

The North Carolina General Assembly is charged with providing a uniform system of free public schools in the state per the North Carolina Constitution. The Elementary and Secondary Education legislation adopted by the General Assembly establishes counties as the geographic area for school administration and also allows city school administrative units to be created within a county or across adjacent parts of two more more counties (G.S. 115C-66). All local school administrative units (LSAU), whether county or city, are administered the same from the state level.

While there are multiple official processes in the books for merging local school administrative units, there is no statutory method for dividing units. Thus, an act of the General Assembly would be required to do so.

During the 2017 Regular Session of the General Assembly, the Joint Legislative Study Committee on the Division of Local School Administrative Units was established. Five meetings were held between February 2018 and April 2018, at which point the committee produced a final report that said additional studies would be needed to create any procedure by which school districts could break up. For more on the committee meetings, read these articles from EducationNC.

In its findings and recommendations, the committee report notes that school size — not district size — is what may actually impact student performance:

“The review of literature and existing studies does not document a relationship between LEA size and student educational performance. However, a strong inference can be drawn that smaller school size contributes to improved student performance.”

The report identifies a variety of decision points that would arise if a district were to be divided, but it does not offer answers to those decision points. In reference to concerns about equality of buildings, programs, and teacher quality that arose during committee meetings, the report says “division of LEAs into smaller LEAs should take care to ensure equality.”

What does the research say?

Available research on the impact of deconsolidating school districts is limited. Much of such research is over a decade or two old, not all studies control for other factors like socioeconomic status, and the findings themselves are mixed. One reason for this is that while there are many available case studies of districts consolidating, there are not many for deconsolidation.

In a report to the Joint Legislative Study Committee on the Division of Local School Administrative Units, Dr. Eric Houck and Dr. Kevin Bastian of UNC-Chapel Hill presented the following conclusion about school district size: there is no perfect fit and no one-size-fits-all solution.

When determining the impact of school district size on financial efficiency, Houck highlighted the tensions that arise between equity, efficiency, liberty, and adequacy. Houck said that a range of studies point to a U-shaped curve of cost efficiencies where inefficiencies in smaller districts decrease as size increases, and then inefficiencies begin to increase once size reaches a certain threshold. These studies point to 10,000 to 15,000 students as the range for maximum cost efficiencies, but the literature is inconsistent.

Some research holds that larger school districts experience diseconomies of scale, or rising per-student costs once they increase beyond a certain size. A 1992 study states that in the previous half-century, “per-student costs rose 6 times, district size rose 12 times, and school size rose 5 times” nationally. In a 2002 study of economies of scale in school districts, researchers found that the administrative savings of larger districts are sometimes offset by increased transportation costs.

Research on the impact of school district size on student achievement is also mixed. A 2018 study that examined school districts in Illinois found no significant effect of district size on student achievement. A 1996 study of the impacts of district and school size in West Virginia found that larger school district size positively affects districts with a high socioeconomic status (SES), but negatively impacts districts with a low socioeconomic status. The report finds that smaller schools and districts offer particular benefits for educating low-SES students, while larger schools and districts offer particular benefits for educating high-SES students.

A 1998 study of schools and school districts found that larger districts are better able to “promote or facilitate” standards-based education reform than smaller districts because they have things like greater specialized areas of expertise and better technical assistance. However, the results showed that the beneficial impact of larger district size is significantly lower when the district is also poor.

Beyond school district size research, a 2013 report from Brookings asks more broadly: Do school districts matter? The report used a decade of data from school districts in Florida and North Carolina and found that districts only accounted for 1 or 2 percent of the total variation in student achievement compared to the contributions of schools, teachers, demographics of students, and other individual differences among students.

North Carolinians weigh in

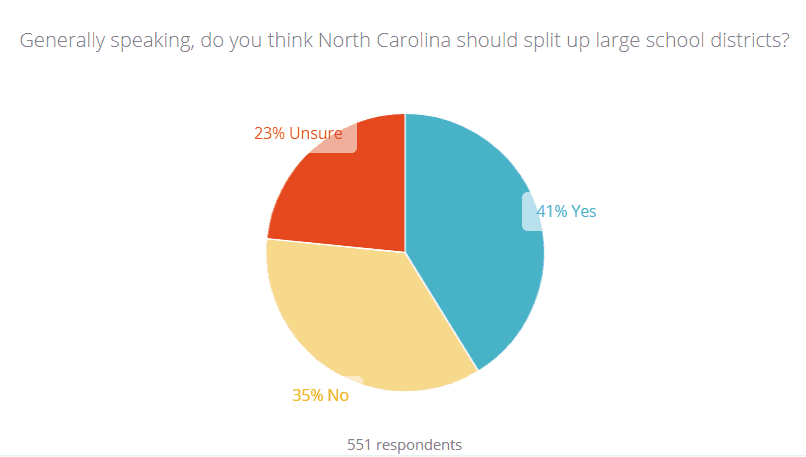

From January 7 to January 11, 2019, Reach NC Voices asked North Carolinians to weigh in on the issue of splitting up large school districts. In that time frame, 551 people responded. Here’s what they said.

Here are a sample of comments from respondents across the state:

“Smaller districts resegregate our state further than charters and private schools already have. For the sake of all kids, larger districts are better because resources are more evenly shared.” — Suzanne from Mecklenburg County

“My biggest concern is when weather comes into play. The whole county is shutdown even if only one side of town experiences a weather event. It would be nice to see the district split up into regions and for each region to have some autonomy regarding closure due to weather as well as allocation of resources. Maybe the district remains unified but regions are allowed to operate independently? I do not want to see schools re-segregated but I do think that our youth spend too much time on long bus rides to schools far away and I think it dis-proportionally impacts our minority students — they get less sleep, have less time to work on school work or be active outside because they spend so much time getting shuttled all over the county in the name of diversity…” — Stephanie from Wake County

“I’ve taught in Duval County Public Schools in Florida and in Warren Consolidated Schools in Michigan. Unlike in Florida, Michigan had many small school districts. I thought it was terribly redundant and contributed to segregation. Big county school districts can try all kinds of things — magnet schools, personalized learning, whatever. I don’t see how a big school district has to stifle innovation. Yes, local autonomy isn’t as great in a larger school district, but the benefits outweigh the drawbacks.” — Barbara from Watauga County

“If it brings back community schools, I am all for it. People live where they choose to live for a reason. Their schools should reflect those communities.” — Anonymous from Durham County

“Many counties with existing split school districts already struggle with segregation issues, as well as funding inequities (poor counties versus wealthy counties), geographic issues, etc. Look at Montgomery County where the wealth is in the west near Lake Tillery. If that county were divided into two school districts the west side would have an unfair advantage over the east side. There is also a disparity between municipal school districts and county school districts within the same county. If any changes need to occur, those split counties should be consolidated to have 100 school districts in 100 counties.” — Mark from Cumberland County

“Our school system is a mess. One of the ways to help fix that is for the parents and community to be able to have a more powerful voice. Currently voices and concerns get lost when you have huge school districts. Teachers and parents need to be able to be more easily heard in our school system and splitting up school districts could help with that problem. As far as potential for desegregation of schools, if parents/students were allowed to choose which school to attend (even if just within a certain radius or district) that could help tremendously.” — Anonymous from Mecklenburg County

To share your own thoughts on this issue, fill out the poll below.

Weekly Insight Education