“Three months after starting college, Brooke Evans found herself without a place to live. She was 19.

She slept in libraries, bathrooms and her car. She sold plasma and skipped meals. It was hard to focus or participate in class, and when her grades fell, her financial aid did, too. Eventually, she left college and began sleeping on the street, in debt, without a degree.”

These are the opening lines of a 2015 New York Times op-ed by Sara Goldrick-Rab and Katharine Broton titled “Hungry, Homeless and in College.” Goldrick-Rab based the op-ed on research she had conducted with more than 4,300 students from 10 community colleges across the country. The results were disheartening. One in five students said they had gone hungry sometime in the last month due to a lack of money, and 13 percent had experienced homelessness sometime in the last year.

Goldrick-Rab’s inbox flooded with people working in higher education across the country saying things like, “We know — this is happening, it’s a problem, and we’re trying to do something about it — but it’s hard.” Goldrick-Rab thought about the value of convening everyone who was working on these issues in one room to show them they are not alone. And so the idea for the Real College convening was born.

Last weekend, over 500 people from across the country — including policy makers, college presidents, nonprofit leaders, students, and social service workers — gathered at Temple University in Philadelphia for the third Real College convening to address food and housing insecurity among undergraduates. During the two-day conference, participants buzzed through the hallways to attend sessions on topics such as creating affordable housing options, preventing food insecurity, addressing the needs of nontraditional students, and integrating mental health practices with basic needs supports.

Barriers to systemic change at community colleges

According to Karen Stout, president and CEO of Achieving the Dream, community colleges often focus on completion as a structural problem within the college or fault the students themselves. But that framework, which defines student attainment of an associate’s degree as the ultimate goal, fails to include what Stout believes is the true work of community colleges: fueling economic mobility.

“If we re-frame the definition of our work, then our problem is not just structural, it’s cultural and social. It is about the work that we’re doing that is so pervasive, especially as community colleges being local institutions, and how we touch everyone in our communities,” said Stout. “This kind of thinking — moving to the question being not how do I improve completion, but how can we break the generational cycle of poverty — changes the conversation on a college campus.”

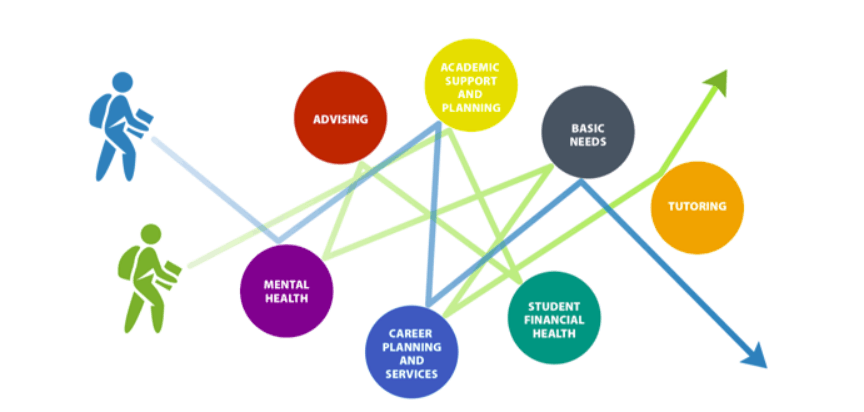

Achieving the Dream works with over 220 community colleges in 40 states to build their capacity for systems change that advances student success. According to Stout, one of the biggest barriers facing many colleges when they first begin working on student success is how fragmented their support services are. At best, a student might receive generic support from a counselor, at worst, they might receive support from no one. Another barrier is the college’s own perception of the role they play as a community college and if they should even be focusing on this work.

“The debate about whether we really should even be taking on this work — around hunger, around housing — is central in some of our early Achieving the Dream colleges where we’re working with faculty and administrators to just define the student success issue.”

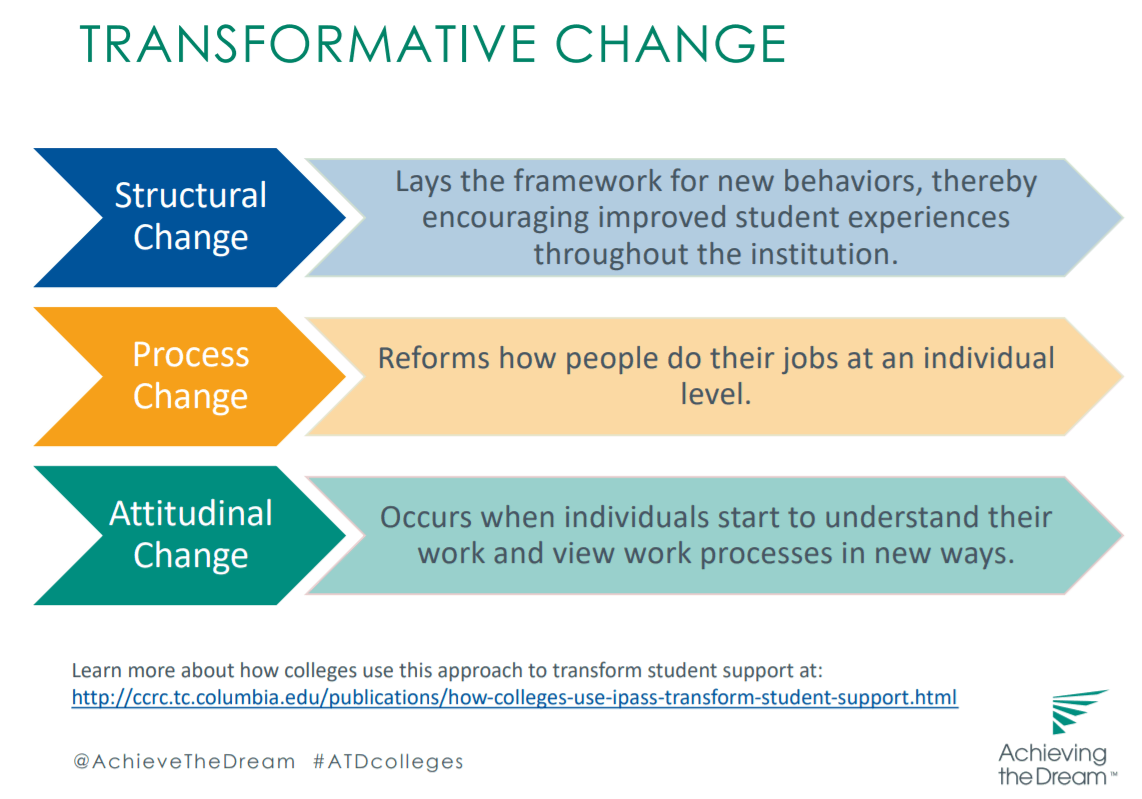

According to Stout, once a college is ready to engage in transformative change, they must think about structures, process, and attitudes; all three of these need to be operating at the same time to truly provide holistic student support services. As a precursor to transformative change, colleges must really know who their students are — beyond the traditional data of race, age, gender, and how many credits they’re enrolled in.

“It’s much more complicated than that in order to really uncover the blind spots,” said Stout. “Do you know how many of your students are single mothers, working part-time, with an income below the poverty threshold, formerly incarcerated, first-generation college students, homeless, or housing-insecure students? Are you collecting that data, how are you organizing the collection of that data, and how are you designing supports and services?”

Once that data is known, colleges can design systems that are suited to their students needs. Knowing the true needs of their students allows the community college to build strong networks of support with them and begins to reduce the stigma that’s often associated with basic needs services.

But Stout recognizes that this work is neither easy nor comfortable. It requires community colleges to completely re-imagine themselves at the center of addressing student poverty and requires them to eliminate barriers to student success that include non-cognitive issues — like hunger and housing. It also requires community college leaders to find new partners in the private, nonprofit, and government sectors and venture to places they may have never thought about. All of this, says Stout, will allow community colleges to truly find systemic solutions.

“I think we are in the midst of sparking the next redesigning, the next renaissance, of what the community college of the present and future should look like, and thinking more about completion as an upward mobility from poverty effort as much as it is about an educational attainment effort,” said Stout.

Creating a culture of caring at Amarillo College

Amarillo College, a rural community college located in the heart of the Texas panhandle, learned who its students truly were in 2011 when it began working with Achieving the Dream. Amarillo collectively refers to its student body as “Maria”: 71 percent first-generation, 55 percent part-time, 55 percent minority, 65 percent female, 54 percent use financial aid, 52 percent have a transfer focus, 54 percent experience food insecurity, 59 percent experience housing insecurity, and 11 percent have experienced homelessness in the last 12 months.

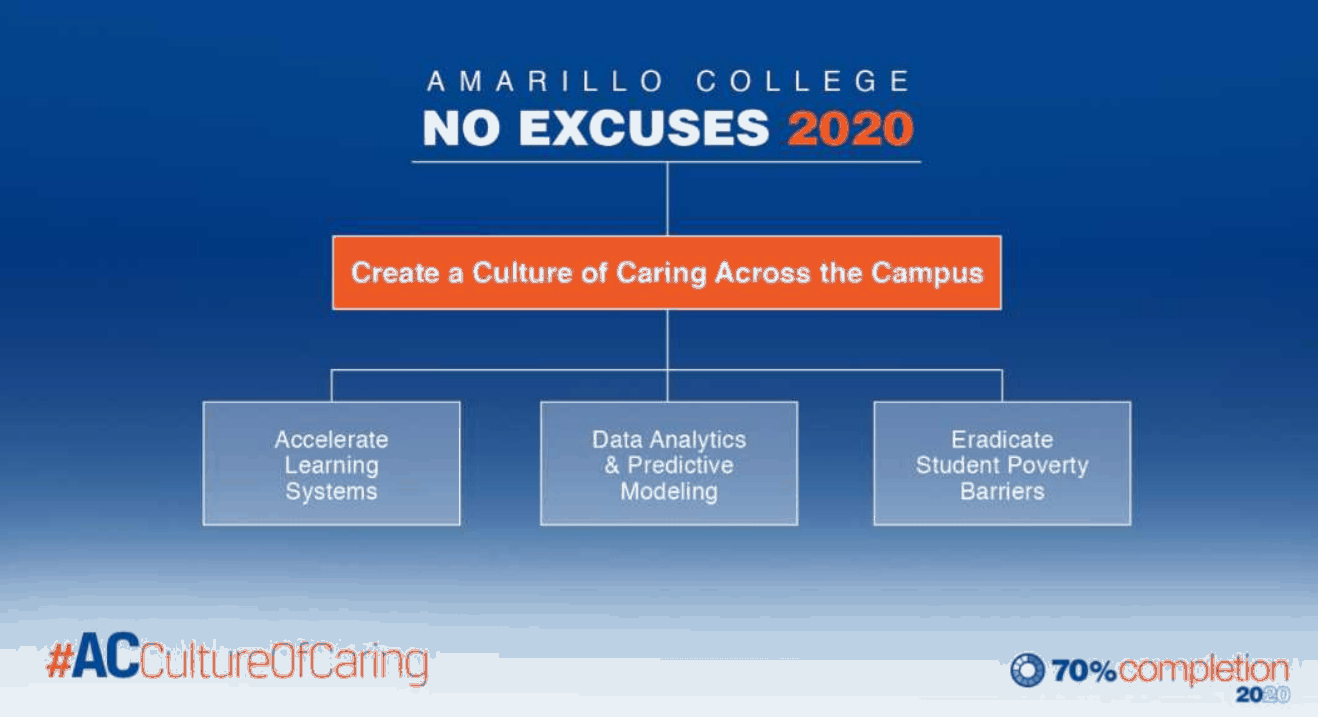

Cara Crowley, Vice President of Strategic Initiatives at the college, believes this kind of robust data provided the first step to the college truly understanding what their students needed. When Amarillo College surveyed students about their barriers to success, the top 10 results were all related to student basic needs — including housing, transportation, child care, utility assistance, and food. Armed with this insight, the college set out to implement a theory of change that would “create a culture of caring across the campus.”

“Our system is set up to keep people in poverty. We’ll address a barrier for food, housing, or transportation — but we don’t think across the system,” said Crowley. “Education will help, and that’s what our advocacy and resource center (ARC) does for our students. Our social workers connect our students to that system and help move them through the system to keep them in school.”

ARC is Amarillo College’s one-stop shop for student services, offering a clothing closet, a food pantry, a legal aid clinic, an employment center, and other social services. To make sure students are aware of what ARC offers, Amarillo College harnesses data analytics.

“We pull students’ FASFA information before they arrive on campus, and if they make less than $19,000, the ARC sends out a simple email to the student to let them know the services are there,” said Crowley. “Because of that, we’ve seen a 400 percent increase in students using the ARC. We went from seeing 600 students to seeing about 2,000 students.”

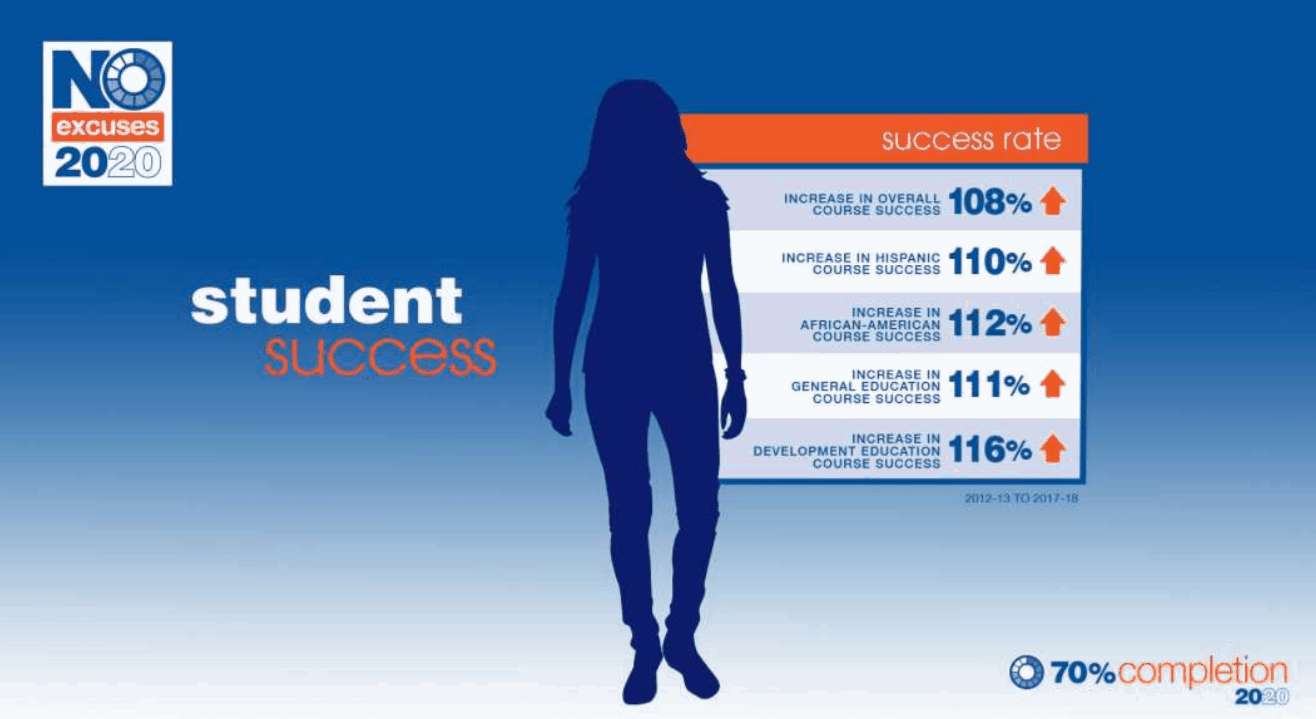

This increase in students accessing the ARC caused a ripple effect across the campus. Metrics like graduation rates, retention rates, and persistence rates have all risen significantly between the 2012-13 and 2017-18 academic years.

Dr. Russell Lowery-Hart, president of Amarillo College, believes the kind of systems change that has occurred at Amarillo College cannot be accomplished by one-off initiatives. Rather, this kind of widespread change requires redefining the very function of community colleges.

Weekly Insight Higher Education“Our job is not to fix students, it is to fix ourselves. Our students are not to blame for the problems they are battling, we are. We’ve adopted a no excuses philosophy; if a student is failing, it means we didn’t have the right person, policy, or process in place to ensure their success,” said Lowery-Hart. “When you can own your students’ success, the amount of disruption that comes will create a movement that will make ‘Real College’ unnecessary 10 years from now.”