North Carolina charter school teachers, principals, and school operators gathered at the North Carolina Association for Public Charter Schools annual conference earlier this week in Sunset Beach. With a theme of “Building Bridges,” speakers focused on how to build collaboration in the education sector and society as a whole.

My father, David Osborne, was one of the keynote speakers at the conference. He presented on his vision for public education, a vision articulated in his recent book, Reinventing America’s Schools. While his argument is most applicable to urban public education systems, there are broader lessons relevant to a largely rural state like North Carolina.

A 21st century school system

In his speech, Osborne said the way public education is organized today is outdated: “So many of our school districts are still operating as if we’re back in the industrial era. They’re centralized, top-down organizations that operate mostly cookie-cutter schools to which students are assigned based on where they live.”

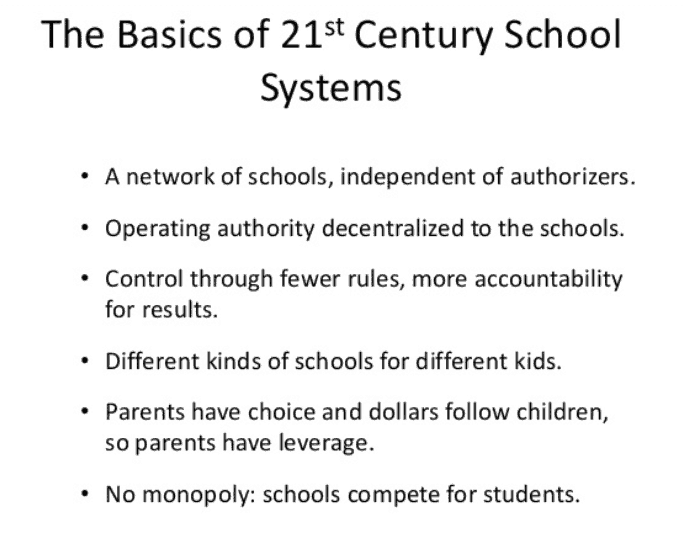

While this model may have worked in the past, he argued, it is failing kids today. Instead, Osborne believes we need a new model for public education where all schools are run like charter schools — public schools that are operated independently and freed from many district rules but held to certain levels of accountability.

The main components of such a system include:

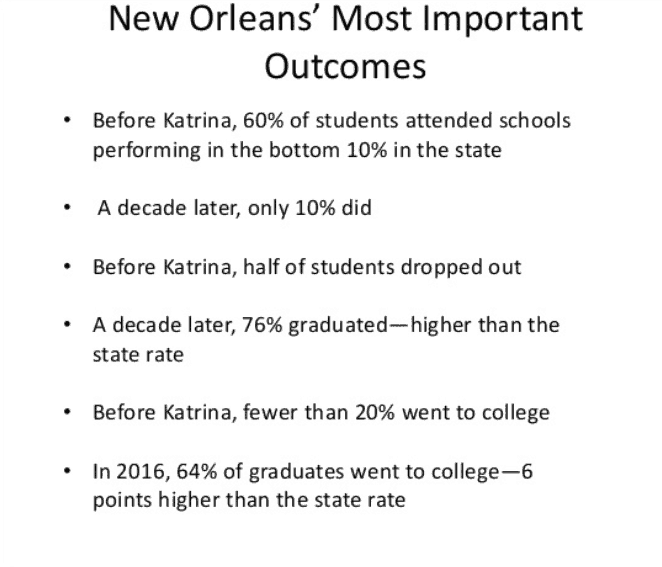

Osborne points to New Orleans as an example of this type of model. After Hurricane Katrina devastated the city, New Orleans turned to a charter model, taking over all the schools in a Recovery School District and gradually turning them over to nonprofit charter management organizations. Now, all but two public schools in the city are charters, and last year the state handed control of the district back to the local elected school board.

In the New Orleans system, students are free to attend any school in the city, and the district uses a common enrollment system called the One App to manage enrollment. Each school is held to certain growth and proficiency benchmarks in their charter contracts. If a school fails to meet those benchmarks, that operator will lose its charter, and the district will invite other charter operators to make a bid to run that school.

The results of this model are impressive. Not only have test scores increased rapidly, but so have outcomes such as graduation rates and college-going rates.

Lessons for North Carolina

This model is designed for urban school systems where multiple schools compete for students, and if one school is closed, others line up to take its place. A system like this could work in large districts like Wake or Charlotte-Mecklenburg but would not work in more rural districts with few schools and few students.

However, the idea of autonomy paired with accountability still holds relevance for rural districts. In this model, districts give teachers and principals the freedom to run their own schools. Schools, not districts, determine who to hire and fire, what curriculum to use, and how to spend their budget. The rationale behind this model is simple — teachers and principals are the best judges of what their students need.

Giving schools more autonomy has gained traction in North Carolina. Low-performing schools can apply for restart status, which gives them charter-like flexibilities. As of March 2018, 103 schools had been granted permission to use Restart. However, increased autonomy has not been paired with increased accountability, something Osborne emphasized in his speech.

Osborne concluded his speech with some advice for the charter sector in North Carolina. He stated:

“There’s one final thing we have to do in the charter sector: We have to keep our own house in order. There are things that discredit charters, for example for-profit virtual charters that have terrible records, and here in North Carolina, white-flight charters. We will never get widespread acceptance of the charter model if it is associated with segregated schools… For the sake of the children, we can’t let that happen.”

Osborne referenced legislation that passed recently allowing four Charlotte-Mecklenburg towns to create their own charter schools and give preference to their own children, saying, “Those will probably be white-flight schools — or I’m told the phrase is now white-fence schools — and we have to limit or stop such practices because they will discredit our entire movement.”

Osborne’s presentation from EducationNC’s event at the Hunt Library in October 2017 is below.

Weekly Insight Education