In February, more than 1,000 North Carolinians participated in an online project called the People’s Session and shared their opinions on various statements related to education in the state. After reviewing at least 10 statements, participants had the chance to add their own statement to the project, creating a largely crowd-sourced list of 103 statements on everything from school safety to teacher pay to calendar flexibility. The goal of this project was to present a mechanism by which North Carolinians could share their thoughts on a number of education issues likely to arise this legislative session.

Here’s how it worked: Participants had the ability to weigh in on a set of policy statements that reflected potential issues and policies that could arise this legislative session. After selecting agree, disagree, or unsure on a minimum of 10 statements, participants could submit their own statements to the project. As project moderators, we reviewed all submitted comments and added some of them to the People’s Session, allowing participants to weigh in on those as well.

Last week, we published an initial look at the results of this project and highlighted the top five statements with the most consensus, as well as the top five most divisive statements. Today, we’ve compiled the full results of the project, with a breakdown of how people voted on all 103 statements. At the bottom of this article you will find more information on how the project was carried out and who participated.

The results

This section includes the results of all statements in the People’s Session, grouped by subject matter. Statements are listed within each category from those with the most responses at the top to those with the least responses at the bottom. EdNC’s team of reporters have also provided brief context on each issue, followed by links to additional resources when applicable.

A note on sample size: With an estimated state population of 10.38 million, a sample size of 384 people is valid at a 95 percent confidence level with a 5 percent margin of error. While many statements in the People’s Session fall above that threshold, others do not. We’ve included all statements from the session below along with their sample size. Statements with smaller sample sizes were added to the project during its final days, resulting in fewer participants viewing them. For demographic information of respondents, scroll to the bottom of this article.

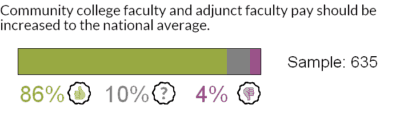

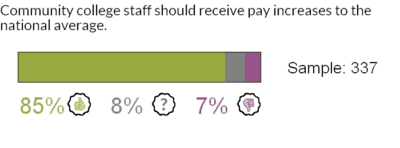

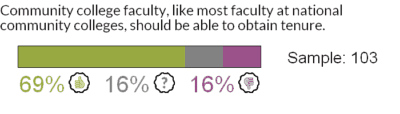

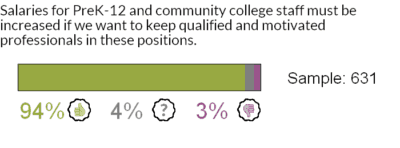

Community college faculty and staff pay

Participants overwhelmingly agreed with pay increases for community college faculty and staff but were more mixed in their support of tenure for community college faculty. For fiscal year 2017-18, the North Carolina Community College System reports an average nine-month faculty salary of $50,293 for the 6,175 full-time faculty members in the system. That figure does not include adjunct faculty or staff salaries and is 2 percent higher than it was in 2016-17.

According to this database by the Chronicle for Higher Education, the national average salary for a full-time instructor at a public two-year institution is almost $72,000. Average staff salaries at public two-year institutions vary greatly based on department, as do adjunct faculty salaries.

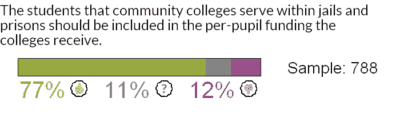

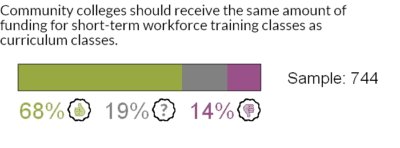

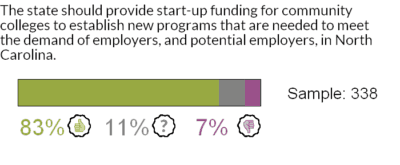

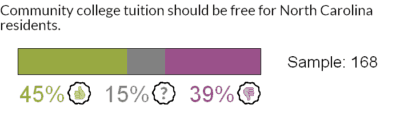

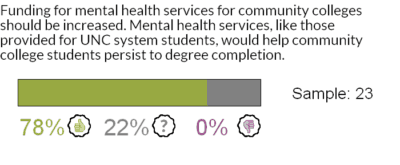

Community college funding

Community colleges in North Carolina get most of their funding from the state’s taxpayers, but the amount each college receives can vastly differ based on things like enrollment and the type of courses offered. County funding, grants, and other donations also help pay the bills, especially to get new programs off the ground. We explain how community colleges are funded in this video.

For more, read our series on community college funding and enrollment.

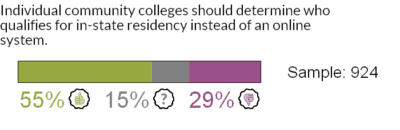

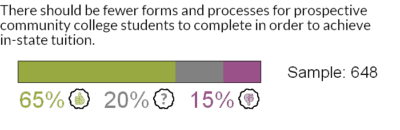

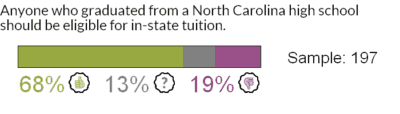

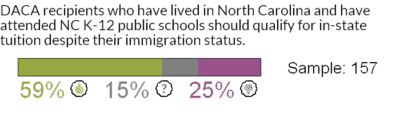

Residency determination

In-state tuition for one year of community college, on average, is about $2,400 in North Carolina, while out-of-state tuition is $8,500 — a remarkable and sometimes game-changing benefit to residents. In order to protect that subsidized rate for those intended, the state legislature enacted laws to determine whether a student is a North Carolina resident. Last year, a new, centralized electronic system went into effect called the Residency Determination Service (RDS) aimed at making the determination process more efficient and consistent.

The system is used for all institutions of higher learning in North Carolina, including the UNC System. And while RDS seems largely to have worked as planned at the four-year universities, community colleges say it lacks the personalization and humanity necessary to address the individual and unique circumstances of their students and has become a barrier to people pursuing continuing education.

For more, read our series on residency determination.

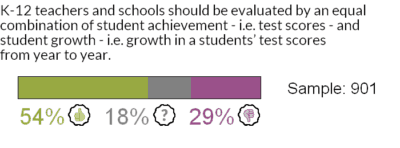

School performance grades

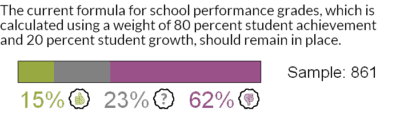

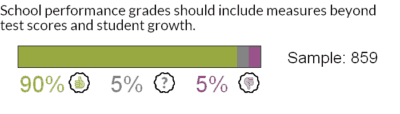

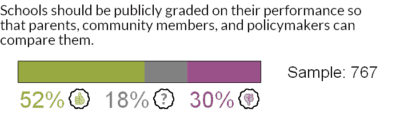

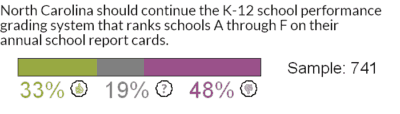

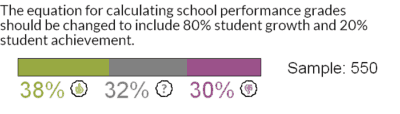

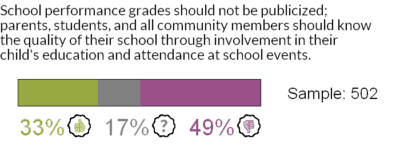

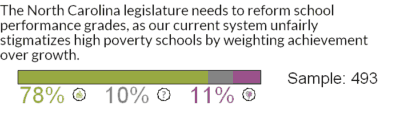

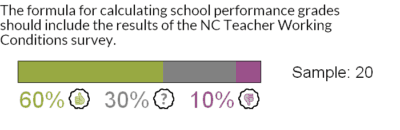

The way in which schools are graded was a frequent user-submitted topic during the People’s Session. Currently, the grades are calculated for every public school in the state using a formula of 80 percent achievement and 20 percent growth. Growth is essentially how much a student learns in a year, whereas academic performance measures how well students do on standardized tests.

The school performance grade formula has been a subject of steady debate in the General Assembly, with some lawmakers advocating for academic growth playing a bigger part in the grades because they say it is a more effective indicator of how well teachers are doing their jobs. Proponents of keeping academic performance front and center say it measures whether students are where the state wants them to be education-wise, so it’s important to keep the emphasis on it.

Last week, a pair of bills that could change the way school performance grades are calculated passed the full House. EdNC will continue to cover these and other potential changes to the grades as this legislative session continues.

For more on school performance grades, see the following resources.

- EdExplainer: How schools are graded and why it matters

- Note: This article is from 2017 and does not reflect current legislation on the issue.

- Mapping the 2017-18 school report cards

- House education committee tackles school performance grades

- House votes to change school performance grades

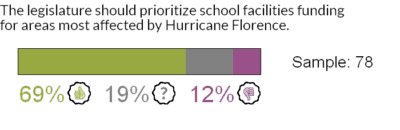

School infrastructure

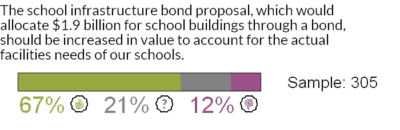

After first announcing his intention to introduce construction legislation at the end of 2018, House Speaker Tim Moore, R-Cleveland, introduced legislation to put a $1.9 billion school building bond before North Carolina voters in late February. The plan would include about $1.5 billion for K-12 schools and about $200 million each for the UNC System and Community College System.

In response to the school infrastructure bond bill in the House, the Senate introduced Senate Bill 5, Building North Carolina’s Future. SB 5 would increase state revenue funds that go into the State Capital and Infrastructure Fund (SCIF) from 4 to 4.5 percent to raise more than $2 billion over nine years for K-12 school construction and maintenance. In late February, the Senate rules and operations committee gave a favorable report to Senate Bill 5.

Senate leaders say their bill would bring more money sooner and would avoid the state going into debt. Moore, as well as other supporters of the bond — such as Gov. Roy Cooper — say the Senate’s plan is no guarantee since future General Assembly’s could decide not to continue using the SCIF funds for building construction.

Meanwhile, the state’s public school systems are in dire need of help. According to a report heard by lawmakers back in 2017, the facility needs in counties around the state were close to $8 billion. That number has only grown over time.

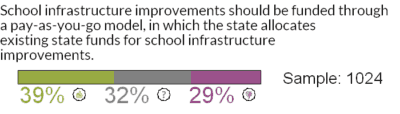

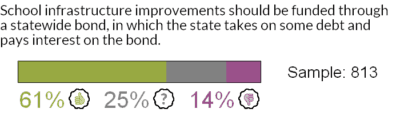

The People’s Session began with two statements on school construction — one reflecting the House plan, and one reflecting the Senate plan. Participants had mixed opinions on both plans, but the House plan received more favorable votes (61 percent agreed) than the Senate plan (39 percent agreed).

For more on school construction legislation, see the following resources.

- Representatives, local officials tour Mt. Pleasant Elementary and discuss House school bond proposal

- Speaker Moore introduces school construction bond legislation

- School construction bond bill makes its way through the House

- Senators strike back against House building bond proposal

- Senate school construction plan clears first hurdle

- State politicians spar over construction bills as Senate proposal moves closer to hearing

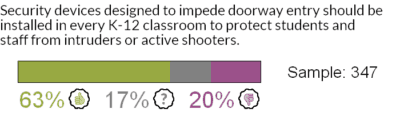

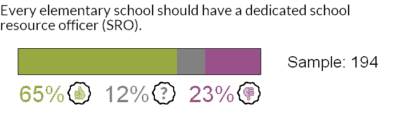

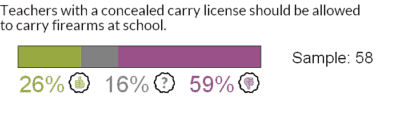

School safety

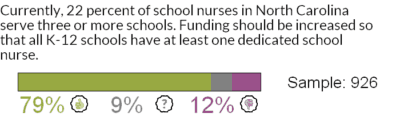

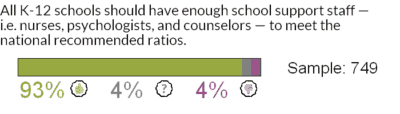

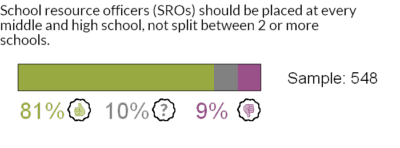

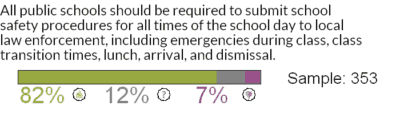

Following the school shooting in Parkland, the House Select Committee on School Safety was created to study and recommend ways to make the state’s schools and students safer. The group met multiple times throughout last year and visited schools to study how to improve the physical and mental wellbeing of students and schools across the state. The committee also split into two working groups with one focused on physical safety (school building structure, school resource officers) and the other focused on student health (school support staff such as nurses, school psychologists, etc.).

A bill with recommendations from the House Select Committee on School Safety — including threat assessment teams for each school and school resource officer training — moved successfully through the House K-12 education committee in late February. In March, House Speaker Moore reauthorized the committee for this legislative session.

For more on school safety legislation, read the following resources, which are in chronological order for clarity.

- House Select Committee on School Safety hears from experts during first meeting

- Subcommittee on student health: More school psychologists needed to keep schools safe

- Governor’s Leandro commission looks at North Carolina’s school support personnel

- House education committee passes school safety measures

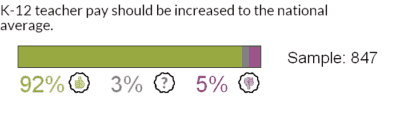

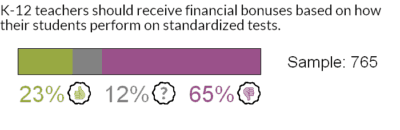

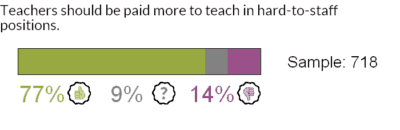

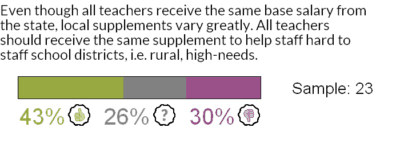

K-12 teacher pay

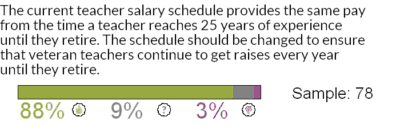

The final 2017 long session budget raised teacher salaries an average of 3.3 percent in the first year of the biennium and 9.6 percent over both years. Starting teachers got no pay raise under the proposal. The highest raises went to teachers with between 17 and 24 years of experience. In the short session budget, the numbers for 2018 were tweaked and teachers ended up getting slightly more, a 6.5 percent increase in 2018 instead of the planned 6.3 percent. Legislators also included raises for veteran teachers — those with 25 or more years of experience — who went from $51,300 a year in the original two-year budget to $52,000 in the short session budget. That change was significant mostly because Republican lawmakers are often criticized for not providing enough of a salary bump for veteran teachers.

Gov. Roy Cooper’s 2019-21 budget proposal includes an average 9.1 percent teacher pay increase. The release of the Governor’s budget is just the first step in the budget process. Both chambers of the General Assembly must come up with their versions before lawmakers hash out a final spending plan.

According to data from the National Education Association (NEA), teacher pay rankings for 2017-18 place North Carolina at 34th with an average teacher salary of $51,231, 18 positions behind the national average of $60,462. NEA estimates for 2018-19 move North Carolina to 29th in the nation with an average teacher salary of $53,975. These projections are subject to change once the fiscal year ends.

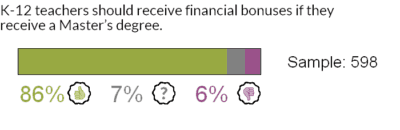

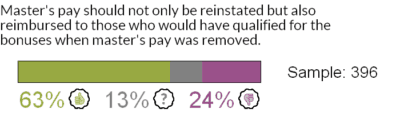

Master’s pay

In 2013, North Carolina became the first state in the country to remove salary increases for educators with advanced degrees, citing evidence that master’s degrees do not raise student test scores (Section 8.22 of S.L. 2013-360). Since then, legislators have introduced multiple bills to restore advanced degree pay for educators, and the debate around whether or not to restore the pay increases has raged on.

Critics of advanced degree pay cite numerous studies that indicate teachers with master’s degrees are no more effective at raising student test scores than teachers with bachelor’s degrees. Proponents of the pay increases view advanced degree pay increases as a tool to keep experienced teachers in the classroom and as a signaling device that rewards a teacher’s choice to further their education, among other things. In early February, a bipartisan group of state Senators introduced Senate Bill 28, titled “Restore Master’s Pay for Certain Teachers.”

For more on master’s pay supplements for teachers, click here.

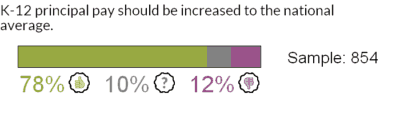

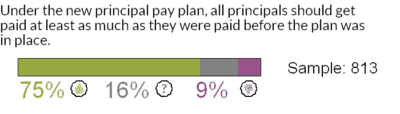

K-12 principal pay

In the 2017 long session, the General Assembly completely revamped the state’s principal pay schedule and increased salaries for principals. They put $35.4 million into principal and assistant principal raises, giving an average 8.6 percent salary increase for principals and 13.4 percent salary increase for assistant principals over two years.

The budget passed during last year’s short session added an extra $12 million for principals, boosting principal pay by an average increase of 6.9 percent for 2018 alone. All this extra money and changes to the schedule were meant to fix a dysfunctional principal pay schedule that EducationNC reported on extensively and bring North Carolina up from its rank as 50th in the nation for principal pay.

There were some wrinkles in the new principal pay schedule, particularly when it came to a controversial hold harmless provision. While most principals received salary increases under the new pay plan, some did not. For those, there was a hold harmless provision that locked their salaries at what they were previously. But the hold harmless had an expiration date. That date was extended by one year in the short session budget last year.

For more on principal pay, read these resources.

- Problems exist with principal salary structure in North Carolina

- EdTalk: Principal pay

- Principal pay calculator

- A little context on principal pay

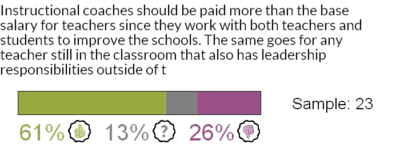

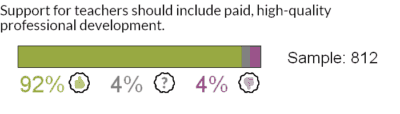

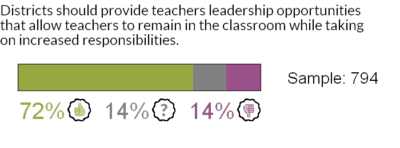

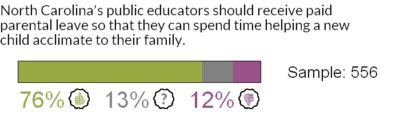

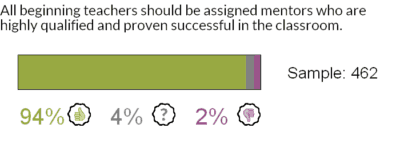

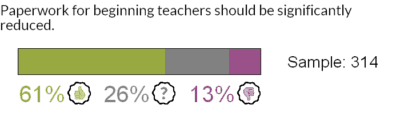

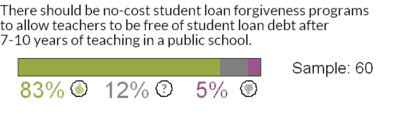

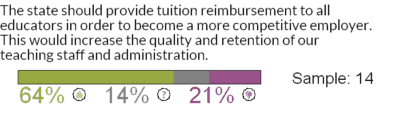

Support and benefits for teachers

Policies like paid professional development and advanced teaching roles, which provide a path to advancement for teachers without them having to leave the profession to become administrators, are included in this category.

The General Assembly budgeted $8.2 million in 2017-18 and $1.7 million in 2018-19 to give grants to counties to pilot advanced teaching roles. Until recently, the state had given out six grants, but at the State Board of Education meeting in January, the board approved additional grants for Bertie County, Hertford County, Halifax County, and Lexington City schools.

The goal of the pilots is to allow districts to test out advanced teaching roles — such as teacher leaders — and differentiated pay in an effort to both sustain the policy when funds run out and see if strategies can be scaled up to the rest of the state. While each pilot is operating slightly differently, the advanced roles they offer often include additional compensation, leadership opportunities, professional development, and more.

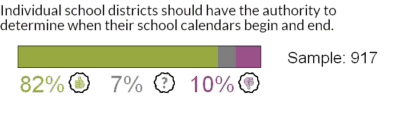

Calendar and school day flexibility

North Carolina mandates two things when it comes to school calendars: how many days students must be in school and when districts can have class. The state says that students must be in school for a minimum of 185 days a year or 1,025 hours of instruction. It also says that schools can’t start earlier than the Monday closest to Aug. 26, and they can’t end later than the Friday closest to June 11.

This creates a host of problems for our geographically diverse state. In the West, schools may unexpectedly miss a certain number of days each year due to snow. In the East, inclement weather — like hurricanes — forces students to miss school as well. But none of this is predictable. So, schools are often forced to jam in make-up days at odd times, like weekends, in order to get all the requisite school time in before the mandatory stop date of the year. Districts argue that if they had calendar flexibility — the ability to start and stop school when they think appropriate — then they could build make-up days into the school year to ensure that extreme measures don’t have to be taken to get kids the instruction that is mandated.

Additionally, districts argue that calendar flexibility would allow them to align their calendars with local community colleges so that students would more easily be able to take advanced classes at these higher institutions. Those are just some of the issues presented by not letting districts have flexibility.

Dozens of calendar flexibility bills have been filed this session, each of which would allow a particular district or set of districts to determine their own school calendar start and stop dates. In March, the House approved House Bill 79, which would allow districts to align their school calendars with that of community colleges.

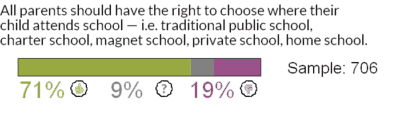

School choice

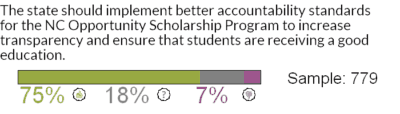

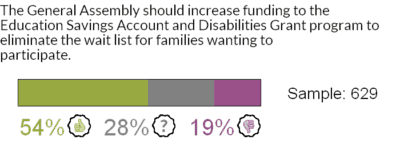

School choice in North Carolina continues to grow, with new charter schools opening every year and the expansion of opportunity scholarship programs for low-income students and students with disabilities. In addition, during the last long session, the budget created an education savings account program, which gives up to $9,000 in public money to families of children with disabilities to use on tuition for non-public schools, books, other supplies, and testing costs.

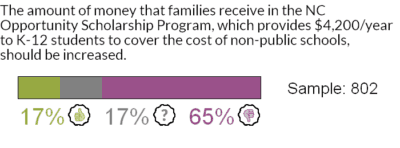

Opportunity scholarships, often called vouchers, give low-income students the option of receiving a $4,200 scholarship to attend a private school of their choice. The General Assembly added $10 million-increases to the base budget of the state for every year leading up to the 2028-29 school year. Last year, the state had budgeted about $44 million for the program, which equates to between 8,000 and 8,300 scholarships. In the 2028-29 school year, the funding will be up to $145 million. It will continue at that rate every year thereafter. That equates to about 36,000 students being able to take advantage of the program.

The disability opportunity scholarship program is similar, but it applies only to students with disabilities.

Statements specifically related to charter schools are in the next section, while this section includes statements related to the Opportunity Scholarship Program, the Education Savings Account and Disabilities Grant program, and other facets of school choice.

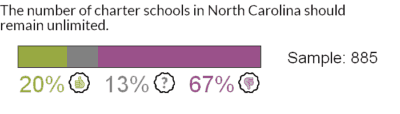

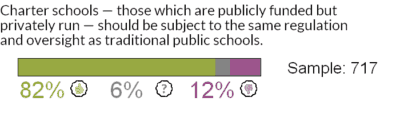

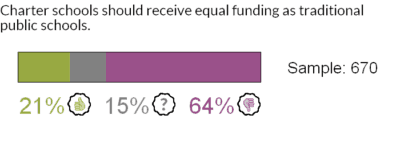

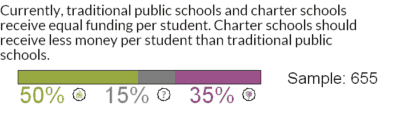

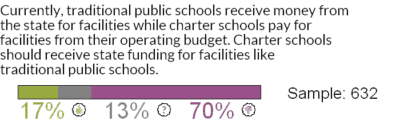

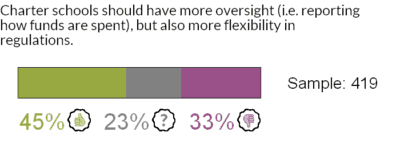

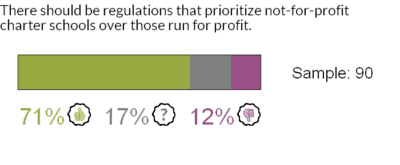

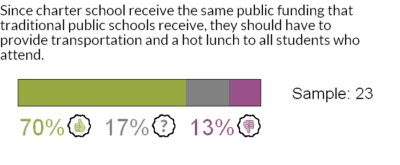

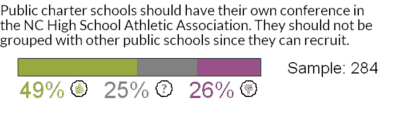

Charter schools

Charter schools are publicly funded but privately operated. Charters are considered public schools, but they are free from oversight and interference from the district in which they live. They are granted certain exemptions from the requirements applied to traditional public schools — things like curriculum, finances, teacher certification, calendars, and more. They can be operated by all sorts of people, organizations, or institutions, including for-profit or non-profit charter management or education management organizations.

According to the latest numbers from the Office of Charter Schools at the Department of Public Instruction (DPI), there are 184 charter schools currently operating in North Carolina, enrolling more than 109,000 students — or 7.3 percent of the state’s public school enrollment. An additional 22 charters are currently in the year-long planning process.

Charter schools are answerable to the state’s Charter School Advisory Board, which makes recommendations to the State Board of Education on who can open, who should close, and whether schools get renewals or not.

Originally, the number of charter schools that could exist in North Carolina was capped at 100. But in 2011, the Republican-led General Assembly lifted the cap, which allowed more charters to open across North Carolina. Senate Bill 247, introduced last week, proposes studying and, at least temporarily, capping the number of charter schools in the state.

For more on charter schools, see these resources.

- School choice continues to evolve in North Carolina, and an update on community colleges

- Charter schools in North Carolina: An overview

- Senate Bill 247 sponsors talk about accountability and transparency for charters

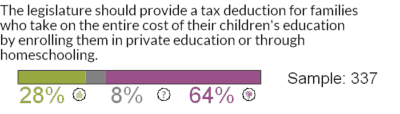

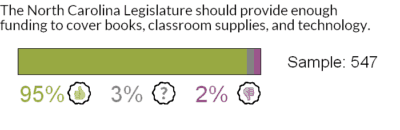

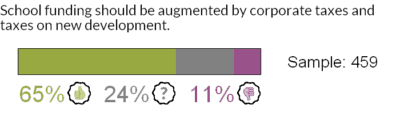

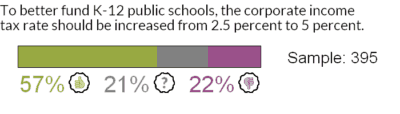

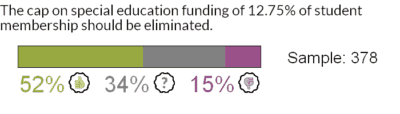

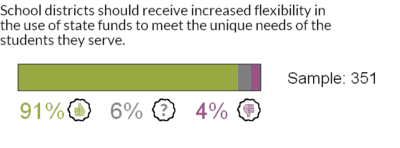

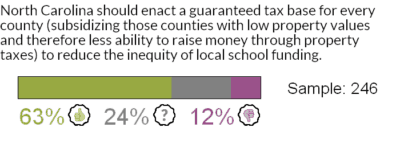

K-12 funding

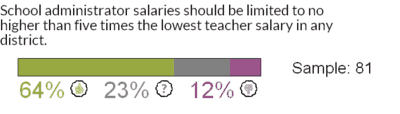

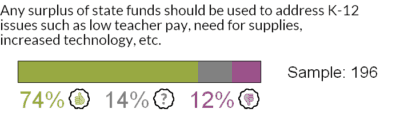

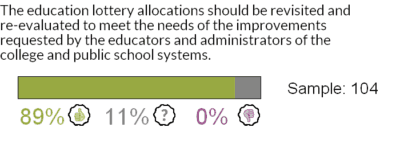

The eight statements in this section were all user-submitted and include topics ranging from funding for classroom supplies to changing the tax code.

The statement pertaining to increased flexibility in the use of state funds was one of the most agreed-upon statements in the People’s Session. Currently, the state doles out funds using a series of allotments — 37 in total. The allotments are essentially line items designating a specific amount for classroom teachers, an amount for school building administration, etc. This is called the resource allocation model. For more on this, read our piece from 2018 on education leaders making a case for increased flexibility.

Such flexibility is currently offered through the Restart program. The Restart program gives some of the state’s lowest-performing public schools more flexibility to make changes in the hopes of improving student performance. The relaxed regulations permit schools to extend the school day, use funds in ways not designated by the state, hire teachers for positions other than those for which they are licensed, and more.

For a closer look at the specific issue of school supplies funding, read this piece from 2017.

For a closer look at how the education lottery functions, read this piece from the North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research.

For more on flexibility in school funding within the Restart model, read these resources.

- How will charter-like flexibility change North Carolina education?

- Restart program gives some low-performing schools flexibility to help struggling students

- After years of struggles, more than 100 NC schools hope new program will lead to success

- Is this flexible program for struggling schools the future of NC public education?

- Starting Restart in North Carolina’s traditional public schools

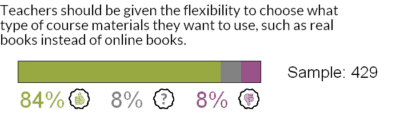

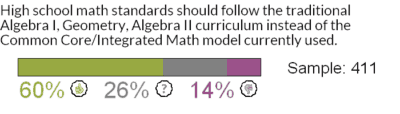

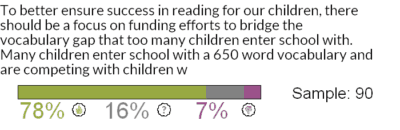

K-12 curriculum

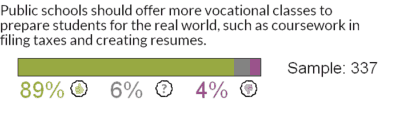

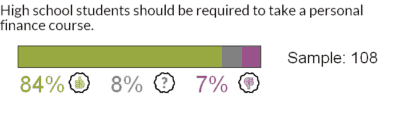

These five user-submitted statements pertain to various aspects of K-12 curriculum and course materials. Two of the statements below reference financial literacy coursework. Senate Bill 134, the “Economics and Financial Literacy Act,” was referred to the Senate Appropriations on Education/Higher Education committee in March and would require “completion of an economics and personal finance course as a high school graduation requirement.”

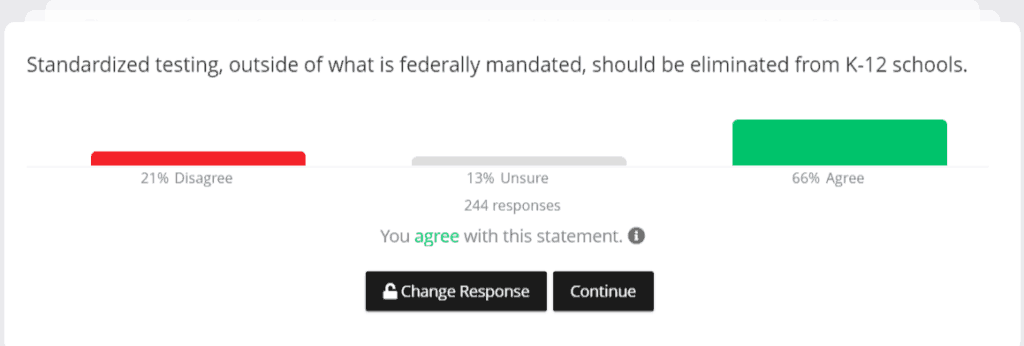

Standardized testing

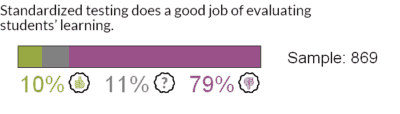

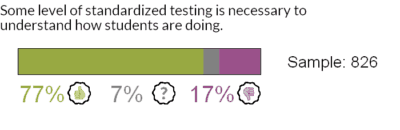

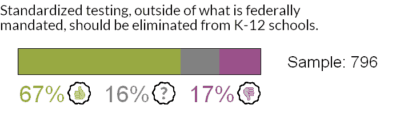

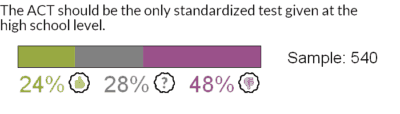

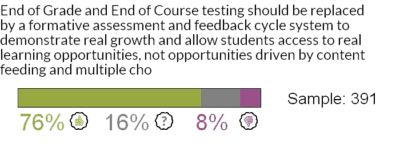

The first two statements on this issue reflect an interesting dichotomy — while 79 percent of participants disagree that standardized testing does a good job of evaluating students’ learning, 77 percent agree that some level of standardized testing is necessary to understand how students are doing.

In November, the State Board of Education discussed and heard a presentation about assessments in North Carolina and the possibilities of eliminating or streamlining them. Representatives from the Department of Public Instruction laid out which tests are required by the federal government, which by the state, and what wiggle room North Carolina has as it tries to lessen the burden on students.

There isn’t much North Carolina can do with tests required under federal law. They can’t be eliminated, though they could be tweaked.

In January, State Superintendent Mark Johnson announced initiatives to reduce the testing currently required for students in North Carolina’s public schools. In March, Johnson released his detailed budget recommendations, including a phased-in plan to increase personalized-learning and reduce high-stress testing.

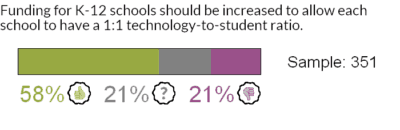

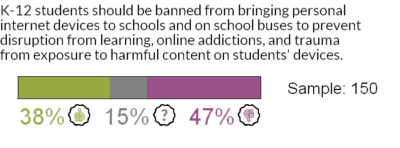

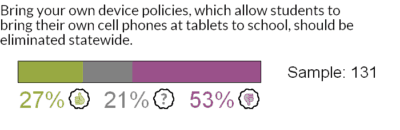

Technology in schools

These three user-submitted statements pertain to the use of technology in the classroom. Two of the statements reflect concern over the use of personal technology devices by students during the school day. As districts and schools further integrate technology into the classroom, both on student-provided and school-provided devices, the role of that technology will continue to face debate.

For more on technology in schools, read our Screens in Schools series.

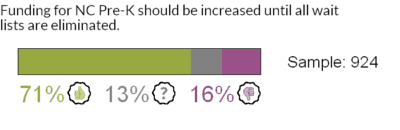

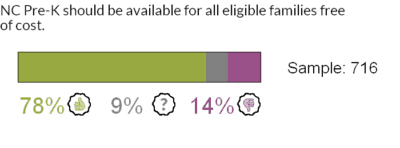

Early childhood education

A recent report by the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), commissioned by a group of North Carolina business leaders, found that 52 percent of 4-year-olds in North Carolina, or 62,287 children, meet the eligibility requirements for NC Pre-K, but only 47 percent of those children are participating.

In the past, the need for increased NC Pre-K funding has been talked about in terms of a waitlist, which in 2017 was believed to consist of 4,700 students. But processes for maintaining those waitlists vary locally, which the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute found in its 2017 analysis. Some counties do not keep a waitlist at all. And the NIEER report found the 4,700 waitlist number relied on the current capacity of the 56 counties that accepted the expansion funding in 2017, not the actual number of unserved eligible children.

Waitlist or no waitlist, the report found 32,778 4-year-olds who could but do not attend NC Pre-K. The first two statements below address increased funding for NC Pre-K to close that service gap, but to differing extents.

For more on early childhood education, read these resources.

- As long session begins, what to expect in early education

- B-3 Interagency Council hones priorities: Transitions, data, NC Pre-K funding

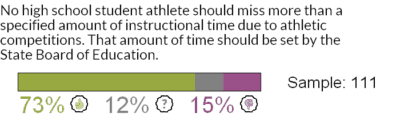

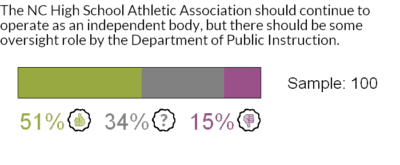

High school athletics

These three user-submitted comments pertain to high school athletics, including policies surrounding the NC High School Athletic Association.

Miscellaneous

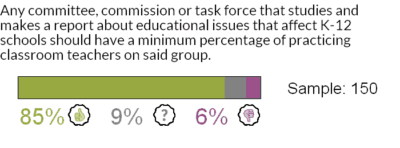

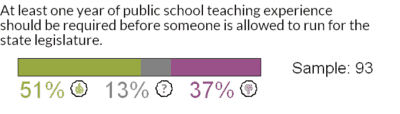

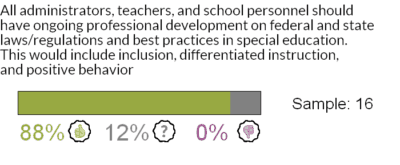

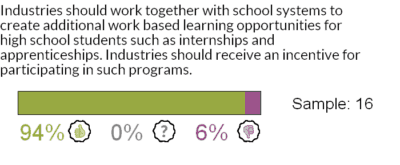

From professional development on special education to alternative educator preparation programs, these eight user-submitted comments didn’t fit into a particular category but address important issues nonetheless.

How did it work?

The People’s Session was hosted on EdNC.org and was accessible via any internet-enabled device, including mobile phones.

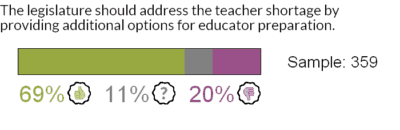

To begin, participants had a chance to weigh in on a set of 35 policy statements originally included in the project. Those statements reflected potential education policy issues that could arise during the 2019 legislative session and were sourced from interviews that EdNC reporter Alex Granados completed with stakeholders across North Carolina. For participants, the voting process looked like this.

Participants could select agree, disagree, or unsure. Then, they received the next statement.

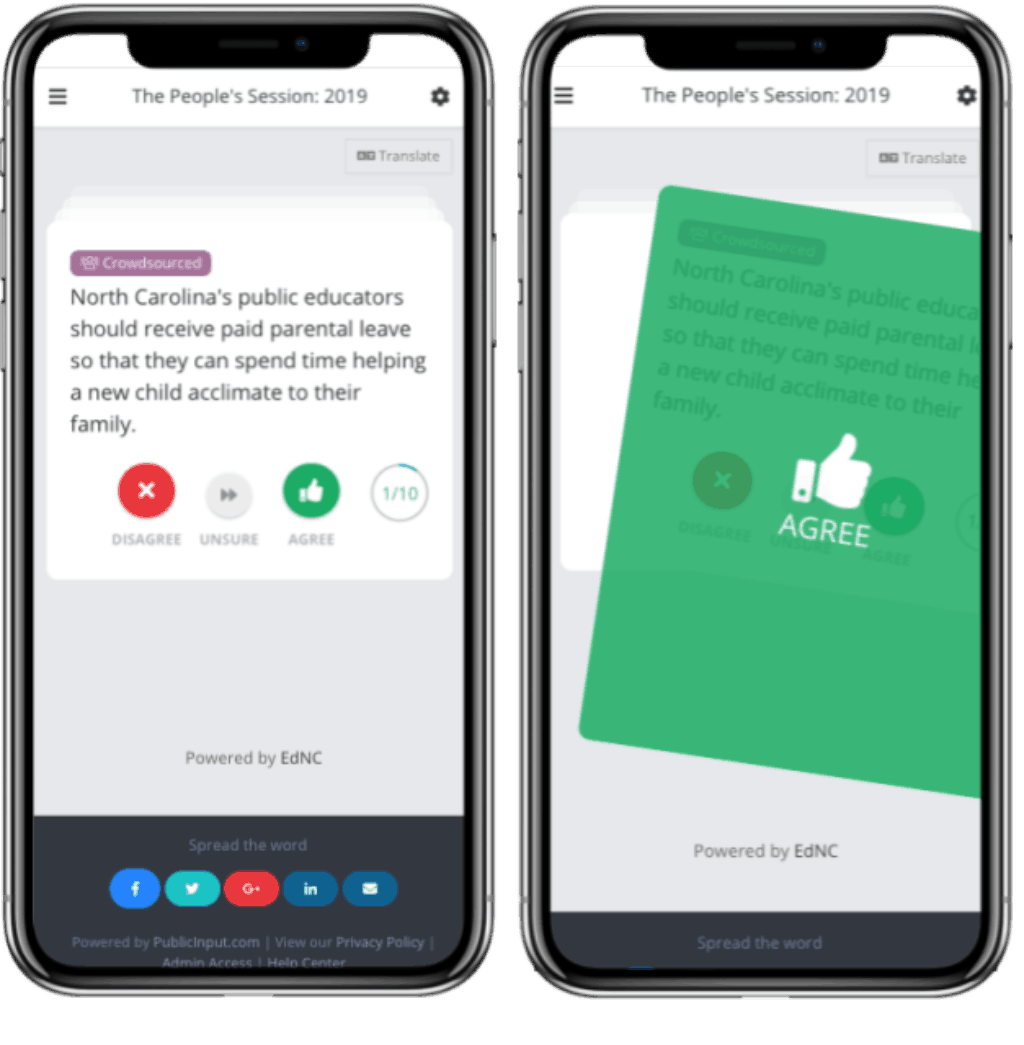

After responding to at least 10 statements, participants unlocked the ability to share their own policy priorities by responding to the question: “What do you think the legislature should accomplish this session?”

Then, their statements were submitted for consideration by our team. If approved, their statement was added to the deck of statements for other participants to weigh in on. A purple “Crowdsourced” button appeared above all user-submitted statements.

As crowdsourced statements were added to the project, our team worked to re-order the deck randomly each day to ensure that every statement had an equal chance at being viewed by a participant.

After answering 10 statements, participants also had the opportunity to view the results of the statements they had previously answered.

Who participated?

Over 16 days, 1,058 people participated in the People’s Session. On average, participants voted on 42 statements each, resulting in a total of 44,611 votes. One hundred and one participants submitted 196 statements on issues ranging from school performance grades to school safety to teacher pay. One participant submitted 12 statements, while others only submitted one.

As the moderators, we rejected roughly two-thirds of the statements, usually in order to weed out duplicates and occasionally because they did not include a policy statement, were inappropriate, or were too vague to be included. Of the 196 comments submitted, 73 were left out for being duplicates of existing statements. This was expected, as users were able to submit a statement after seeing only 10 of the statements in the project. Twenty-nine statements were left out for not including a policy issue or statement, while another 26 statements were left out for being too niche or too vague for a statewide conversation.

In the end, the project included 103 statements, 35 of which were originally included in the project and 68 of which were added by participants.

Most of our participants joined the People’s Session after receiving an email inviting them to do so. Over the course of two weeks, our team sent 181,000 emails to the roughly 90,000 parents, teachers, students, and other community members on our email lists. As shown in the graphs below, participants were disproportionately white and highly educated, both of which reflect the demographics of North Carolina educators.

Although we also publicized the event on social networks, we did not attempt to ensure a randomized participant pool. Therefore, we cannot define the margin of error for the responses or extrapolate the results to the broader population of North Carolina.

In order to better understand who was participating in the People’s Session while still encouraging a high response rate, demographic questions were optional and listed below the People’s Session questions on the page. Of the 1,058 total participants, 362 submitted demographic information.

Weekly Insight Education