In an age marked by political division and a reported decline in civil discourse, there are too few areas of bipartisan consensus and cooperation. The opioid crisis is one area where everyone is on the same page — the problem is real, pervasive, and devastating.

Last week, Attorney General Josh Stein along with legislative and community leaders unveiled the latest response to this public health crisis. The bipartisan HOPE Act, sponsored by Rep. Gregory Murphy, R-Pitt, Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, Sen. Jim Davis, R-Cherokee, Clay, Graham, Haywood, Jackson, Macon, Swain, and Sen. Tom McInnis, R-Anson, Richmond, Rowan, Scotland, Stanly, is a product of the Attorney General’s North Carolina Law Enforcement Opioid Task Force and represents a substantive expansion of the investigative and prosecutorial tools available to law enforcement in combating this crisis.

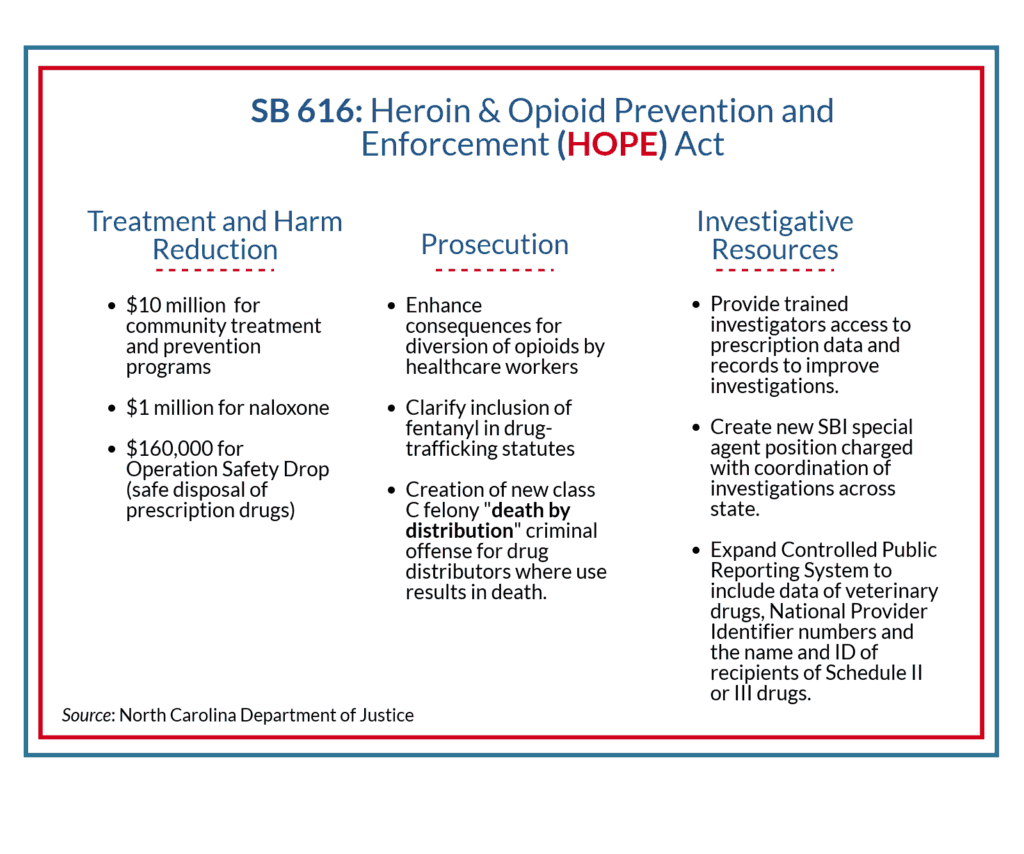

The HOPE Act’s expanded tools for the tool box fall in three broad categories:

- community investment in treatment and harm reduction,

- enhancement of investigative support and resources, and

- clarification and expansion of prosecutorial powers.

This includes a $10 million investment in community treatment, $1 million for naloxone, the creation and funding for a designated State Bureau of Investigations officer to coordinate drug-trafficking investigations, and expanded access to drug prescriptions data and records through the Controlled Substance Reporting System.

While generally lauded as a critical “step in the right direction,” there is one component that may prove controversial — the creation of a new Class C felony offense carrying a prison sentence with a minimum of 10 years if a drug distribution results in the death of the user. Some in law enforcement argue that this expansion of the criminal code is necessary in order to reduce the supply of drugs in their communities.

While generally lauded as a critical “step in the right direction,” there is one component that may prove controversial — the creation of a new Class C felony offense carrying a prison sentence with a minimum of 10 years if a drug distribution results in the death of the user. Some in law enforcement argue that this expansion of the criminal code is necessary in order to reduce the supply of drugs in their communities.

Pender County Sheriff Carson Smith Jr., president of the North Carolina Sheriff’s Association, observed that this new criminal classification removes a “big hurdle” in prosecuting drug distributors for the deaths in overdoses:

“It used to be, if we wanted to charge somebody with murder, one of the big hurdles we had was, in murder, you had to have the malice… In this new law, should it go in, we’ll be able to charge somebody with killing somebody because they sold them dope and they died, and we don’t have to prove malice — and I think that’s a great thing.”

Under the existing statutory framework, drug traffickers can be charged with second degree murder for deaths resulting from use of the illegal substance where prosecution establishes direct and proximate causation, intentional and unlawful distribution of the drug, and malice.

It is the final component that some law enforcement representatives, including Sheriff Smith, have identified as a stumbling block.

In common language, malice connotes a deliberate act intended to wreck a specific harm upon a person. However, it also includes reckless acts or omissions “done in such a reckless and wanton manner as to manifest a mind utterly without regard for human life and social duty and deliberately bent on mischief.” Examples of malicious criminal acts include driving while intoxicated, high speed car chases, or firing a gun into the air in a public space.

The disparity between common use and legal terminology creates confusion, argues New Hanover District Attorney Mark Davis. He believes opioids such as fentanyl are unique not only in terms of their impact on the community but their known lethalness, not least due to the pervasive adulteration of the drug creating “bad batches.”

“No one can say that they don’t know fentanyl or heroin is not deadly. We are losing three North Carolinians a day to these substances.”

Davis speaks from experience. Last year, Wilmington, part of Davis’s jurisdiction, was identified as “ground zero” for the crisis with over 11.6 percent of the population addicted to opioids. As such, the New Hanover and Pender County police departments and district attorneys are front line witnesses to the epidemic and its human cost.

“Anyone who has done my job for a day would see how this meets a real need…. We need to raise the cost of business for people profiting from this poison,” Davis said.

No one argues with the fact that North Carolinians are hurting. However, there is concern that this punitive approach, reminiscent to some of a regressive war on drugs, will not offer the relief sought. There is no evidence that expanded criminalization or punitive efforts will deter the drug trade or reduce overdose fatalities. Overdose prosecution may “fulfill an instinct for retribution,” but there is no consensus on its purpose or evidence of efficacy. If passed, North Carolina will provide a testing ground for the impact of this type of legislation.

Weekly Insight Health & Human Services