Nearly five months have passed since the 2016 election, and the tide has begun to ebb from politics to governance. The election results become less a part of the current event cycle and more political science.

Practically speaking, candidates have made their final filings with the Board of Elections and have closed the books on the campaign. The closure means data wonks and armchair political analysts can begin gleaning from the results and building on the historical body of conventional wisdom about elections.

One of the most interesting and difficult-to-explain outcomes of the North Carolina election results were the statewide Council of State races. For every nugget of political wisdom that exists, the North Carolina Council of State results seemed to provide an opposing example. Think that there is an incumbency advantage? Incumbency seemed to help Republicans other than Pat McCrory but did not help half of the incumbent Democrats. Believe that there is gender advantage for women? Cherie Berry, Beth Wood, and Elaine Marshall all won, but Linda Coleman and June Atkinson did not. Assume that campaign expenditures lead to victory? The money differential clearly made a difference for Josh Stein, Dale Folwell, Dan Forest and Steve Troxler but did not help Wayne Goodwin or Charles Meeker.

The Center gathered, aggregated and synthesized data about the election. Below are six data points from the 2016 Council of State races.

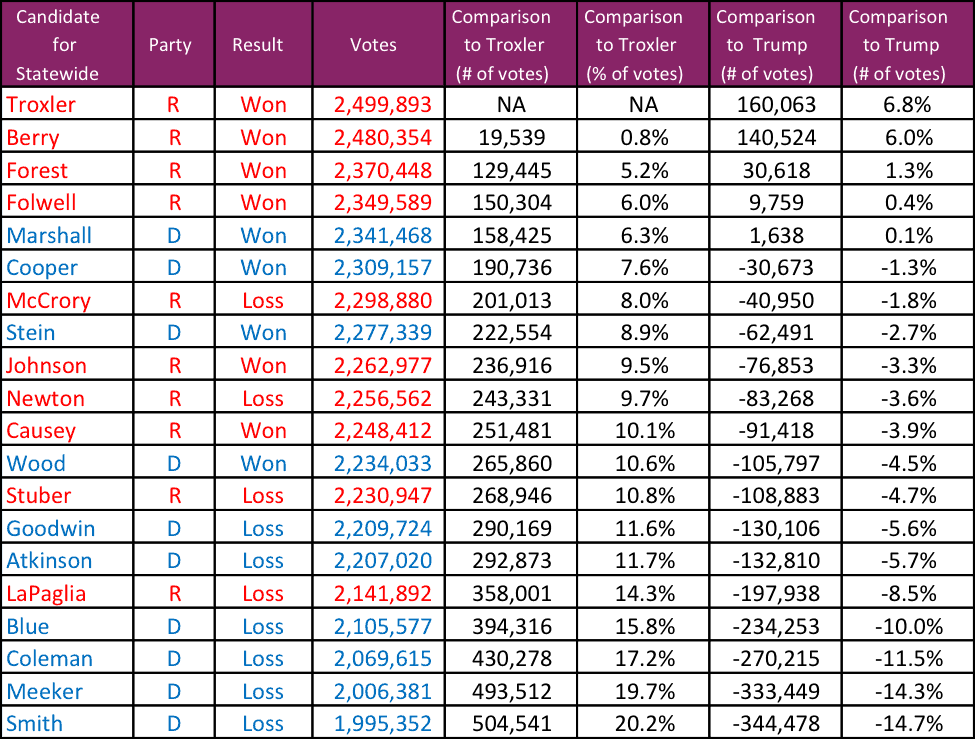

1. Fear the Tractor

The most popular statewide elected official in North Carolina is Commissioner of Agriculture Steve Troxler. Commissioner of Labor Cherie Berry was a close second in terms of total vote amount. At nearly 2.5 million votes each, they outpaced President Trump by more than 6 percentage points, Lt. Governor Dan Forest by more than 5 percentage points and Governor Roy Cooper by 7.5 percentage points.

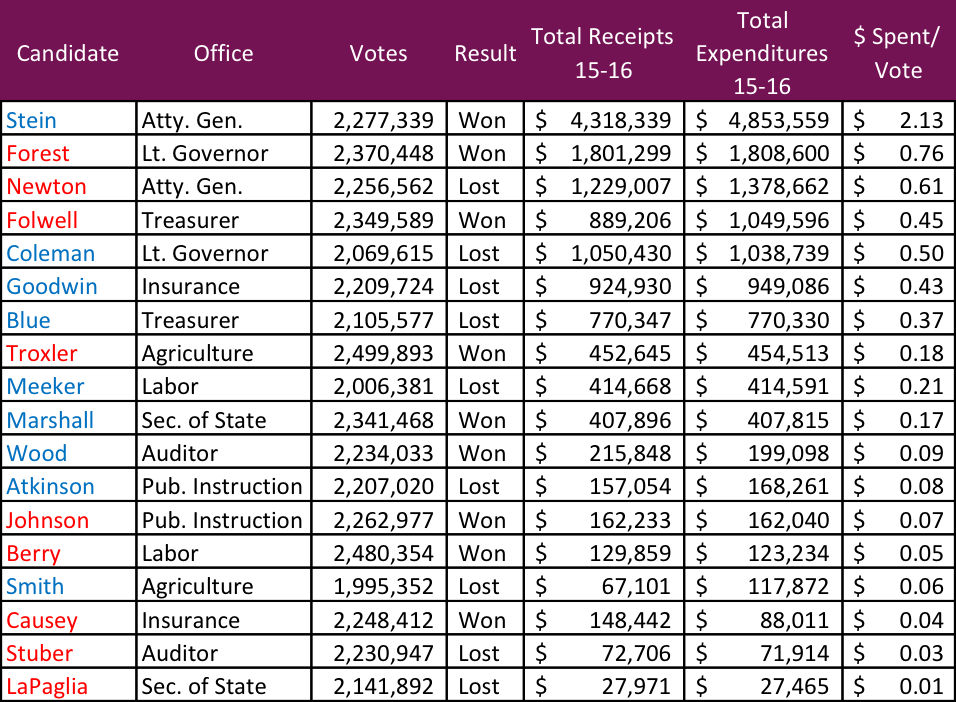

2. The effect of money down ballot is difficult to determine

As President Donald Trump showed in the 2016 Presidential election, money does not always create a path to victory. The chart below lays out the receipts and expenditures of Council of State candidates other than Governor. Overall, these results raise more questions than provide answers.

Costing more than $6.2 million between the two general election candidates, the race for Attorney General was the most expensive down-ballot race. Josh Stein spent 3.5 times more than Buck Newton and won by 20,777 votes. Despite the spending gap, Newton was still the third highest spender among Council of State candidates.

In a losing effort, Charles Meeker out spent incumbent Labor Commissioner Cherie Berry by nearly 4 to 1 but lost nearly by 473,973 votes.

Insurance Commissioner Mike Causey spent the least amount of any winning Council of State candidate. He spent less than $100,000 dollars on the race – $861,076 less than incumbent Wayne Goodwin.

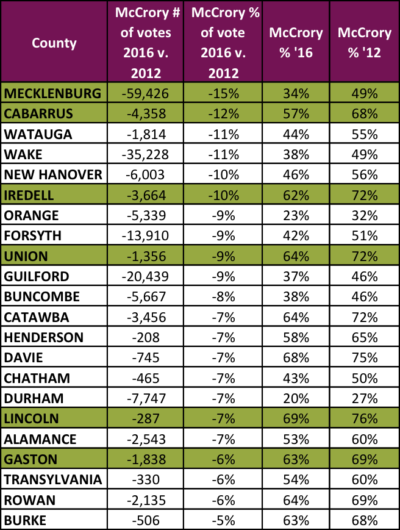

3. McCrory attrition

Controversies in the Charlotte Metropolitan region, be they the I-77 Toll Road or House Bill 2, had an effect on former Governor Pat McCrory’s vote totals. Statewide, 22 counties saw the McCrory vote percentage fall by five percentage points between 2012 and 2016. Mecklenburg County and its five adjacent counties all were in that group.

Additionally, the McCrory vote totals in the state’s five largest counties dropped substantially between 2012 and 2016. In Mecklenburg, Wake, Guilford, Forsyth and Durham counties, McCrory lost 136,750 votes and average of 10 percentage points over the four years.

4. Third-party candidates matter

Libertarian gubernatorial candidate Lon Cecil won 102,977 votes for governor, or approximately two percent of the total votes cast for that office. The final margin of victory for Governor Roy Cooper was 10,277 votes, or 10 percent of Cecil’s vote total.

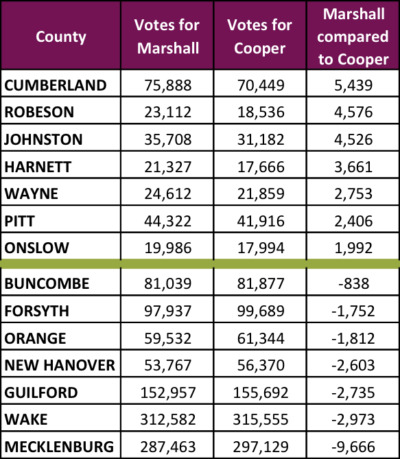

5. Slightly different strategies for Cooper and Marshall

Governor Roy Cooper and Secretary of State Elaine Marshall were the highest Democractic vote getters on the Council of State, but they reached victory in slightly different ways.

Both candidates won more than 2.3 million votes, with Marshall winning about 59,000 more than Cooper.

Cooper won approximately 22,000 more votes in the Democratic stronghold counties: Mecklenburg, Wake, Guilford, New Hanover, Orange, Forsyth and Buncombe. Attorney General Josh Stein’s vote totals roughly mirrored Cooper’s in these areas.

Marshall won more votes in Eastern North Carolina. She won a little more than 25,000 votes than Cooper in Cumberland, Robeson, Johnston, Harnett, Wayne, Pitt and Onslow counties.

6. Democratic incumbent results are tough to explain

There were four Democratic incumbents on the Council of State. Two won, and two lost.

As discussed above, Secretary of State Elaine Marshall set the standard for Democratic votes totals. The race for Secretary of State attracted between 13,000 and 25,000 more total voters than the other four races. Marshall won 108,665 more votes than fellow winner State Auditor Beth Wood and approximately 135,000 votes more than former Superintendent June Atkinson and former Insurance Commissioner Wayne Goodwin.

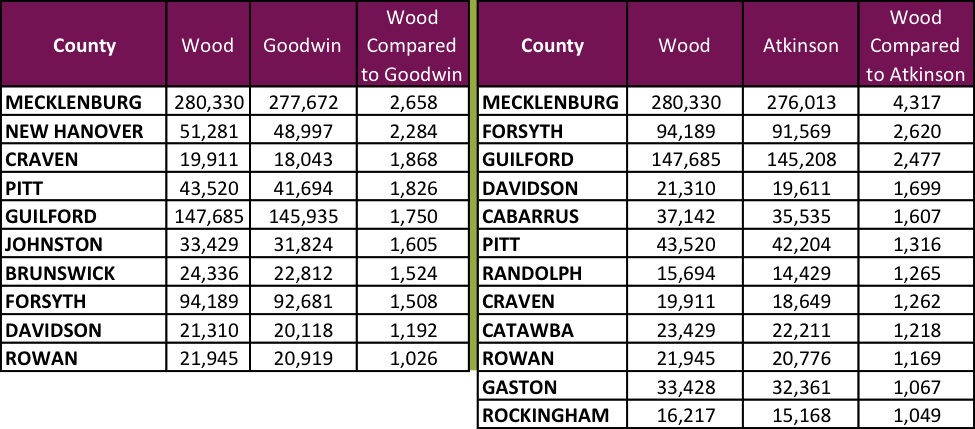

Wood had the narrowest margin of victory among Council of State candidates in this election defeating challenger Charles Stuber by 3,086 votes. Wood won approximately 25,000 more votes than the two losing incumbent Democrats, Atkinson and Goodwin.

There are no clear explanations for what determined these four races, though a couple of notes stand out. First, Wood and Marshall won more votes in Triad and Charlotte regions than did Atkinson. These margins were small–1,000 to 4,000 votes per county–but they added up and could not overcome Atkinson’s stronger performance in the Triangle region.

Second, Goodwin also had relative disparities in the Triad and Charlotte, though to a lesser degree, but did comparatively worse in the larger eastern counties: New Hanover, Pitt, Craven and Brunswick. Again, these differentials were small, all less than 3,000 votes, but they added up and contributed to the gap.

Final thoughts

It is easy to get lost in election data and lose sight of how to transfer information into knowledge. When the tide begins to flow towards the 2020 election season, one should note several observations about statewide races in modern North Carolina.

First, it is hard to argue that anything except the most intense fundraising effort is worth the energy for down ballot races. Future Council of State candidates may be facing the tough choice: up the ante and aim to raise $3 to $4 million, or abandon traditional fundraising efforts and focus on grassroots campaigning, social media and earned media. The conventional wisdom used to be that $1 to $1.5 million would be a strong showing for a Council of State race. Today, with the state’s growing population and the noise of being a national “battleground state,” that may not be sufficient to get the word out. If not, candidates should think carefully about how to spend their time.

Second, for many candidates, the time-tested strategy of focusing on all 100 counties may not be the most effective. Statistically speaking, the population differential between the state’s 20 to 25 most populous counties and the rest of the state is stark. The difference does not mean people in one place matter more than others, or that the local issues on those counties are more important, but victories in those counties provide clearer paths to closing voting gaps. It does not matter whether those counties are red or blue. A Republican that loses Wake County by 20,000 votes fewer than the average Republican may well fare better than one who wins by a higher percentage in smaller, strongly Republican counties.

Finally, there are no infallible maxims in state politics. Gender, incumbency, and money can all affect an election, but the precise formula for victory differs for every race.

Weekly Insight Politics