Water is like health; we take it for granted until it is threatened. Over the last 18 months, we have witnessed two significant water disruptions: one in Flint, MI and the more recent Super Bowl weekend outage in Chapel Hill-Orange County, NC.

To be clear, the underlying issues, culpability and scale in these disruptions were different. The water contamination in Flint was the result of criminal conspiracy to mislead and a poorly developed change in how Flint sourced its water. In Orange County, the weekend without water was the result of an unfortunate succession of unusual events.

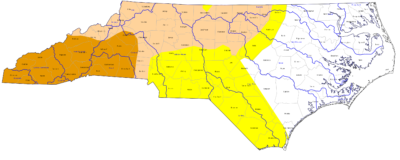

North Carolinians are used to thinking about droughts. Parts of the state have been in one stage of drought or another for much of the last 20 years.

Outside of droughts, however, we have been lulled into a largely thoughtless social contract: we pay a nominal amount in taxes and utility fees, and some utility will ensure that our commodes will flush and our taps will turn on. The thoughtless element is a tribute to our engineering success. In the United States, drinking water quality and distribution are issues largely conquered generations ago, and we have developed an expectation that our seamless system will continue.

The problem is that—like any large, complicated, physical system—our water and wastewater infrastructure requires regular attention and maintenance. Some water operators are the efficient custodians of our expectations. Others, however, are burdened with lesser financial flexibility, weaker political leadership, or both. In addition, the nature of water infrastructure is subterranean, making citizen oversight and accountability more difficult to monitor. Citizens may not recognize inefficiency until they feel its financial impact—a recognition that may be disconnected from the point of origin.

From a policy perspective, we cannot always assess where the trouble bubbles will arise. The Orange Water and Sewer Authority (OWASA) was a stable utility, yet it was still susceptible to a massive, short-term failure. If it can happen in Chapel Hill, what other communities in the state are susceptible?

Financial and infrastructure weakness

In the last three years, the number of local governments in questionable financial circumstances has risen from 66 to 166, according to Greg Gaskins, secretary of the N.C. Local Government Commission, in a recent conversation with EdNC and N.C. nonprofit leaders.

There are a number of culprits for the rise: an imbalance between the number of finance officers retiring from and coming into the workforce, a complex public accounting system, and lagging local economic recovery in areas outside the state’s core metros. However, perhaps the most widespread and common element affecting local government financial health is the maintenance and management of local water and sewer systems.

Much of this state’s water infrastructure is aging and needs investment. According to the NC Department of Environmental Quality Division of Water Infrastructure, over the next 20 years, capital cost estimates for water system needs range from $10 to $15 billion, while costs for wastewater system needs range from $7 to $11 billion.

For the last four years, the State Water Infrastructure Authority (SWIA) and its predecessor, the State Water Infrastructure Commission (SWIC), have considered the water infrastructure challenges. Earlier this year, SWIA released its water infrastructure master plan, which describes the state’s challenges and proposes potential approaches.

Here are several important points of context:

- Statewide, approximately 8 million North Carolinians are served by public water systems, which is about 80 percent of the state’s population. The remainder use household wells as their water supply.

- Of the 2,000 community water systems operating in the state, one-third of these systems have customer bases of 100 people or less.

- The smallest 1,800 of these systems serve about 10 percent of the state’s population. In contrast, the 10 largest water systems serve 30 percent of the state’s population.

- Compared to most states, North Carolina has a large number of independent, local government water and wastewater systems, including incorporated municipalities, counties, sanitary districts, water and sewer authorities and others. Hundreds of separate water systems are owned by not-for-profit associations, for-profit water companies, and by property managers such as homeowners’ associations and mobile home park owners.

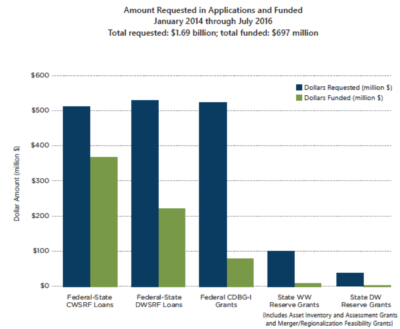

- In the past three years, the State Water Infrastructure Authority reviewed requests for more than $1 billion in loan funds and more than $650 million in grant funds. Funding was only available to fund $600 million in loans (60 percent of requests) and $97 million in grants (15 percent of requests).

- Only a small fraction of water capital needs—just 7 percent of drinking water infrastructure needs and 8 percent of wastewater infrastructure needs—can be met by grants.

The SWIA master plan is an important document and residents should find some comfort in knowing capable policy minds are thinking about the problem. That said, the issue is fundamentally a local one. The state is available to coordinate resources, to share technical support, and to respond to situations that have already been identified.

But the onus is on local governing boards, local political leaders, and ultimately on citizens to appreciate the responsibilities of our current water systems. The successful continuation of our current system is not inevitable, and it will clearly have significant additional cost.

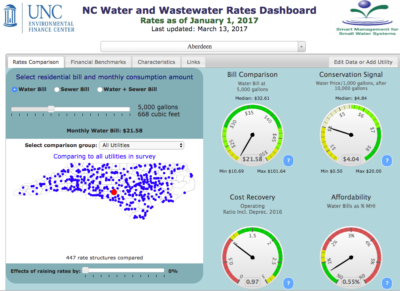

As citizens and policymakers seek to better understand water infrastructure issues, the UNC School of Government’s Environment Finance Center created a dashboard tool for assessing local utilities. It allows for a variety of comparison points. A strength of the dynamic tool is that it is useful to average citizens as well as seasoned water technocrats.

Recent water crises have raised public awareness of the complex issues around water supplies. Two important questions emerge: How do local communities respond? Will communities be able to pay the deferred maintenance and upgrade costs?

Weekly Insight Environment