One of the days I remember best from teaching involved one of my favorite fifth grade students, Amiri. After redirecting her for talking during independent reading, she blew up at me, telling me she could do what she wanted and did not care what I said.

Hurt and confused by this unexpected reaction, I wrote up a referral to the dean and told her to see me at lunch. When she came to my classroom later, she sat down and began crying, apologizing to me while explaining that her uncle, who was like a father to her, had passed away the night before from a heart attack, and she did not know how to deal with it.

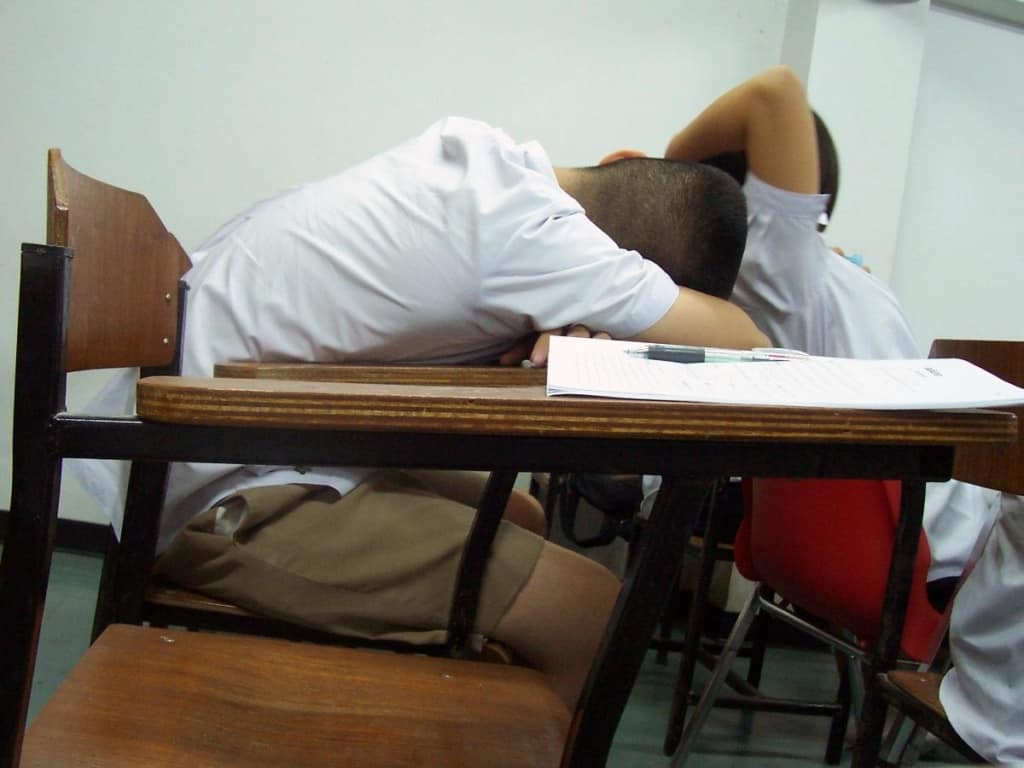

When I first learned about adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, Amiri’s face immediately came to mind, along with the faces of several other students. It was a light bulb moment for me; here was an explanation for why Ronjae, normally a quiet young man, would sometimes erupt in anger over the slightest things, such as a classmate stealing a pencil. Or why Corey was sometimes withdrawn and spaced out to the point that I thought he might be sleeping with his eyes open. These reactions were classic signs of the body’s reaction under too much stress.

What are adverse childhood experiences?

If you are not in the medical or education fields, you have probably never heard of ACEs — although there is a good chance you have never heard of ACEs even if you are in one of those two fields. ACEs, or adverse childhood experiences, are traumatic experiences that occur during childhood and may affect a person’s health and wellbeing as a child and later in life.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) defines two types of trauma. An acute traumatic event occurs at a particular time and place, and chronic trauma refers to trauma that occurs repeatedly over a period of time. Both types of trauma can have significant effects on children’s brain development.

Discovery of the effects of childhood trauma

The first study to document the effects of childhood trauma grew out of an obesity clinic run by Dr. Vincent Felitti, chief of Kaiser Permanente’s Department of Preventive Medicine. Dr. Felitti inadvertently discovered that the majority of his obese patients had been sexually or physically abused as children. In response to this abuse, his patients put on weight to make themselves less attractive or physically dominant. Dr. Felitti realized gaining weight was not the actual problem, but rather the solution, for many of his patients.

Expanding his survey further, Dr. Felitti partnered with Dr. Anda of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and together they screened more than 17,000 patients at Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997. The patients in the study were majority white, middle-class, middle-aged, and all had jobs and healthcare.

The results of the study were astonishing. In order to categorize their results, Drs. Felitti and Anda developed 10 categories of what they called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as experiencing emotional, sexual, or physical abuse and neglect, having a parent who died or parents who divorced, having a mother who was a victim of domestic violence, or a parent who was an alcoholic.

They counted each type of adverse childhood experience as one point. Drs. Felitti and Anda found two-thirds of the patients in the study had experienced one or more types of adverse childhood experiences. One in eight had a score of four or higher, demonstrating the prevalence of trauma among “average” Americans.

The link between ACEs, brain development, and schools

The most significant revelation of the ACEs study, however, was not the prevalence of childhood trauma but the link between childhood trauma and medical problems as an adult. More childhood trauma meant much higher risks for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis, sexually-transmitted diseases, and autoimmune diseases, to name a few.

In small amounts, these hormones are not dangerous, but when someone is repeatedly subjected to trauma, these hormones are constantly activated and the brain cannot return to normal. The effect of this over time can result in allostatic load, a condition where one’s brain fails to return to a normal state of functioning and instead becomes either hyper-responsive or hypo-responsive. In children, this can look like a child overreacting to a small trigger (like my student Ronjae) or one who is barely responsive (like my student Corey).

Combating ACEs in schools

Knowing how our brains respond to stress, it is unsurprising that children suffering from trauma do poorly in school. Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician in San Francisco, found her patients who had four or more ACEs were 32 times more likely to have learning or behavior problems in school than children with no ACEs.

Chronic stress in children has been linked to higher school absences, impaired attention and concentration, reduced creativity and memory, higher rates of anxiety and depression, and reduced motivation and effort. Much of the disruptive behavior we see in schools directly relates to stressful home environments. Impulsive and disruptive behaviors function as survival mechanisms for brains under constant stress, yet most schools are unable to see these disruptions as symptoms of trauma.

The research discovering the effect of ACEs is now 20 years old, but many schools are just now learning about it and asking what they can do. While schools cannot control their students’ home environments, they can train staff on ACEs and implement trauma-sensitive practices. Creating trauma-sensitive schools involves training staff on the effects of trauma and shifting the mindset from “What is wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

In North Carolina, one school district is leading the way. At the Adverse Childhood Experiences Southeastern Summit in Asheville, North Carolina, leaders from Buncombe County described efforts to create trauma-sensitive schools and build resilience in the community.

Buncombe County’s experience addressing ACEs

Buncombe County established an ACEs Learning Collaborative comprised of community members from many different sectors, including education, social work, medical, and healthcare. Together, they committed to raising awareness about ACEs and addressing them in their community. They established a common narrative and resource guide but realized this was only the beginning in trying to address ACEs and build protective factors in their communities.

Buncombe County Schools began training their staff on ACEs and building resiliency in their classrooms, both for students and teachers. They started with the teachers because if the teachers are not regulated and healthy, the classroom will not be either. They now have comprehensive counseling programs and a full time counselor in each school.

County leaders realized each school was different and needed a different approach that worked for their students. At one school, students taught their parents about resiliency skills by putting on a play. Teachers realized that many parents did not show up for teacher meetings or school nights, but they would come to see their children in a play.

So far, the data from Buncombe County is promising. County leaders said their students’ socio emotional skills have increased as well as their academic scores.

Moving forward

Trauma-sensitive schools are gaining momentum in other areas of the state as well. The Public School Forum is working with Edgecombe County Public Schools and Rowan-Salisbury Schools this year to implement trauma-sensitive practices through their North Carolina Resilience and Learning Project.

As word of these school districts’ efforts to create trauma-sensitive environments spreads, more schools will hopefully follow suit. It is time for schools and communities to play an active role in addressing ACEs and building resiliency.

Weekly Insight Education Mental Health