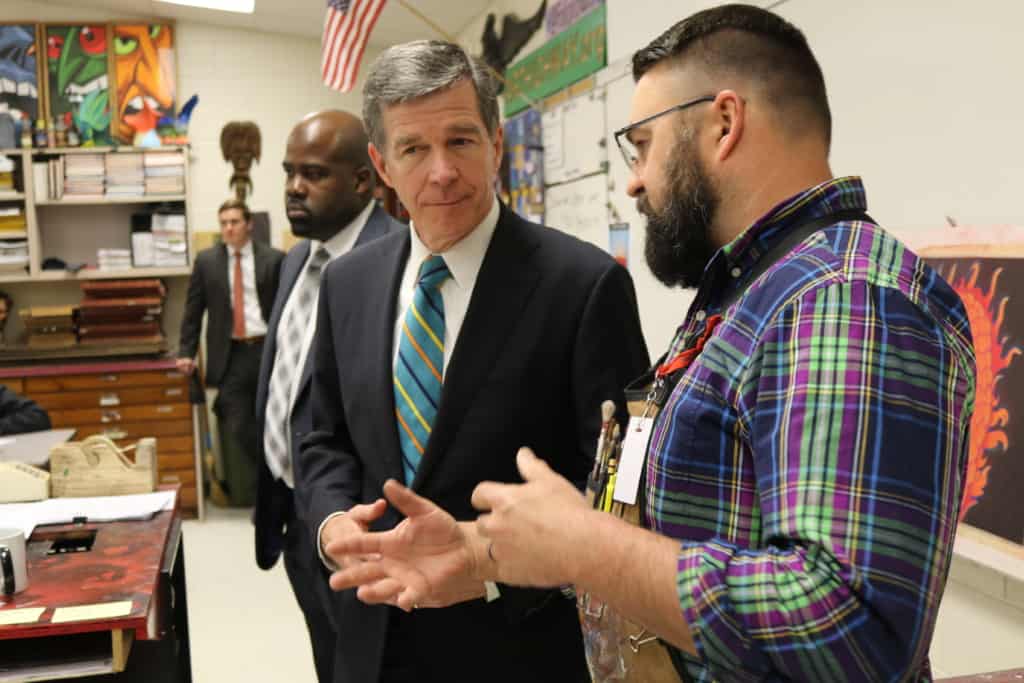

Earlier this week, Governor Roy Cooper launched the State Reentry Council Collaborative. According to the press release, the Collaborative “will examine the needs of people being released from prison and ways to help them successfully reintegrate into their communities.”

This sounds like a worthwhile pursuit and made me think, why doesn’t the state engage more commissions, collaboratives and other similar exploratory bodies to try and address our policy problems?

It is fair to say that state and federal policymaking processes are tense right now. Public policy is not exactly flowing swiftly out of Washington or Raleigh these days. There are many reasons for that: political bandwidth, capacity, deep partisanship, and issue complexity to name a few.

Some of North Carolina’s most successful policy ideas arose from commissions that preceded legislation, e.g., N.C. Comprehensive Estuarine Blue Ribbon Committee, which led to the Coastal Area Management Act of 1973. These efforts provided the opportunity to vet ideas, build solutions and seek broad support of the political process. There are six reasons why we should create commissions to examine and respond to some of our toughest policy problems.

1) Provide a platform for stakeholders to engage directly. Too often, stakeholders are left to choose between blunt instruments for policy engagement: public opinion and the formal legal and legislative processes. Commissions provide a more nuanced alternative and create distinctive opportunities for stakeholders to communicate directly and even work together to establish common boundaries for discussion.

2) Provide an opportunity to harness expertise. Issue experts, like other stakeholders, are often outside the day-to-day political process. Commissions allow for expertise—whether it is researchers, specialists or people who have dealt with similar issues elsewhere—to be formally connected to the policy process.

3) Diversify thought leadership. Public policy debates often affect many people beyond experts and stakeholders. Commissions provide an opportunity to bring other perspectives into a discussion in ways that can bring in broader viewpoints. In addition, commissions involve community members who are not currently serving in policy leadership roles, which can serve to increase active participation in the public process.

4) Solutions need time to simmer. When faced with a problem, it is natural for citizens and advocates to want quick solution. Sadly, our political process is not built for speed. Rosa Parks kept her seat in 1955 but the Civil Rights Act was not legislated until 1964. Commissions allow for policy recommendations to evolve, take shape, and then simmer a little bit until the political process is ready for them.

5) The current political process is not creating results. Recent high profile efforts at proactive public policy have floundered, e.g., healthcare and tax reforms. Commissions provide distinctive opportunities to start or continue the policy making process when the political process is not ready to move or lacks the capacity to do so.

6) Engaged parties are specifically asking for it. Stakeholders in some of our most pronounced social and political debates are giving clear signals that they want the types of opportunities commissions provide. For example, in the memo to NFL Commissioner Roger Goddell from four NFL players requesting social justice concessions, the players list among their proposals: “Participation in high-profile educational institutional events or Conferences, such as keynotes, panel discussions and participation in workshops.” In addition, they list “engagement with bi-partisan federal, state and local organizations and non-profit initiatives focused on criminal justice reform to identify and receive information on legislative efforts, garner resources as well as support to distribute and amplify content/Op-Eds, letters, etc.”

A thought experiment: assume that a Governor or legislative body were to authorize 10 public commissions at a cost of $2 million total. Further assume that two of the 10 led to clear legislative action. The other eight had positive legislative effects on the margins but provided an outlet for public discussion and stakeholder involvement. In a state with a $20 billion budget, does one-tenth of one percent seem reasonable for that kind of action?

Where are the best opportunities to convene commissions? We are looking for areas where there is popular demand for political movement but where the political process has not yet been able to step up. Furthermore, it is important for successful commissions not to be overly broad. We have had numerous commissions on tax reform, for example, and with questionable results. Here are four commissions from which North Carolina or the United States might benefit.

1) Charter school lessons learned – Charter schools are more than 20 years old in North Carolina. They were and continue to be justified as opportunities to experiment with different education structures and to be laboratories of pedagogical models. Anecdotally, we have learned a lot, but we have not devoted much energy to systematically assembling best practices and applying the learning to the public schools.

2) Statistical disparities in criminal justice – The policies and practices in apprehending and punishing people through the criminal justice system is the source of significant debate. Many of the underlying issues are multifaceted and are connected to deep philosophical debates. There are, however, statistical disparities in how the criminal justice system apprehends and punishes lawbreakers and potential lawbreakers. Acknowledging and studying these disparities can be an important step to addressing social tension and lead towards more systematic policy changes to the system as a whole.

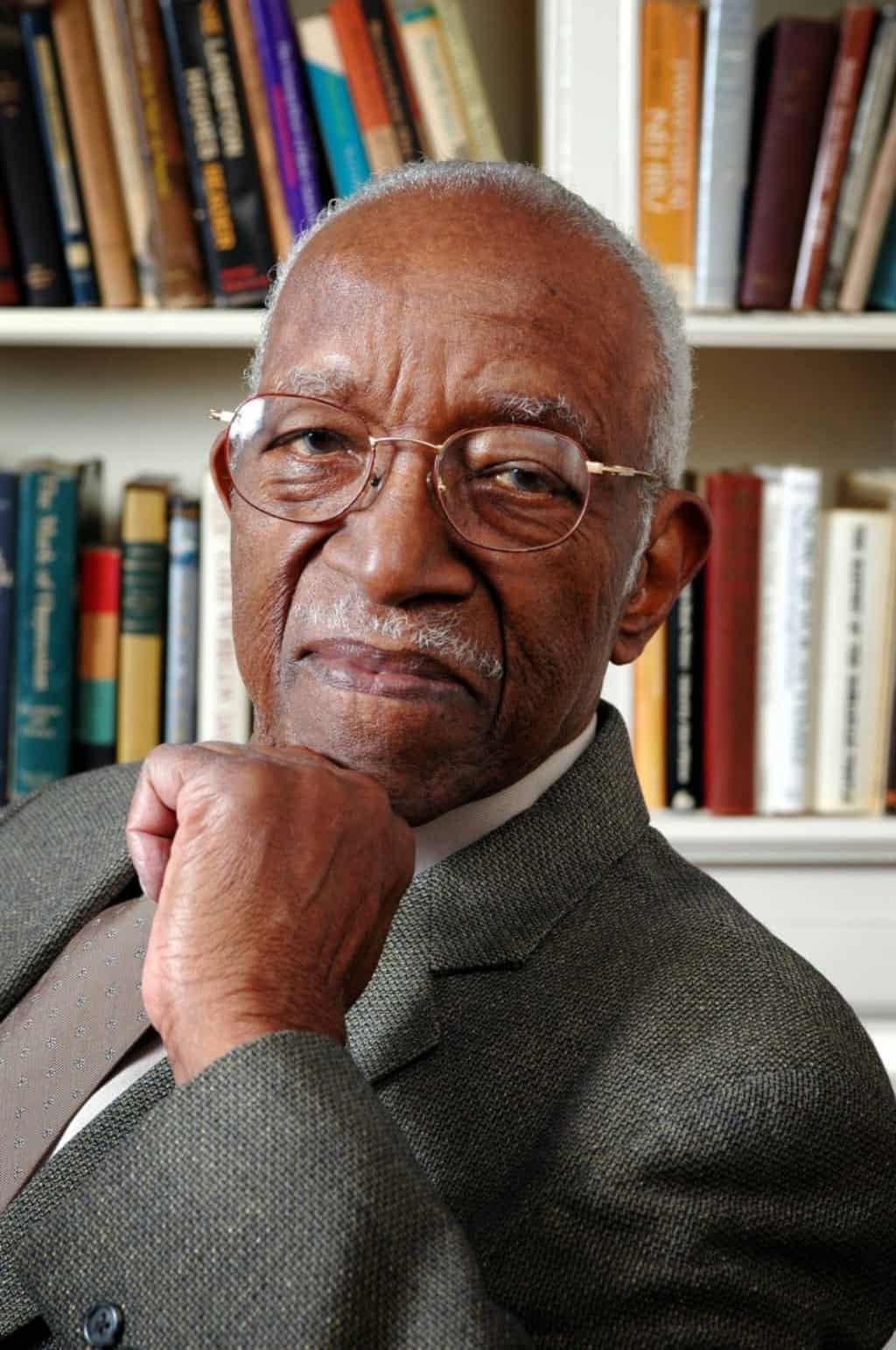

3) Race relations in 21st century – In the 1990s President Clinton formed an initiative on race, One America in the 21st Century, which was chaired by Duke historian John Hope Franklin. The initiative published best practices for racial reconciliation and dialogue guidelines designed to help communities discuss how to address racial and ethnic divisions in mutually productive ways. More than 20 years later, with the seeds of racial discord growing in multiple policy issues, it is time to systematically revisit the issue.

4) Cybersecurity and personal information – The Equifax and Facebook political advertising debacles have brought this to a new light. Experts have begun thinking about whether identifiers like social security numbers make sense in today’s age. In addition, understanding the relative cost and benefit of data protection options will help inform a public policy discussion that needs guidance and perspective.

The beauty of commissions is that anyone can initiate them. While many state-level commissions are sanctioned from the governor or the legislature, that need not be the case. They simply require a base level of resources and someone with the gravitas to recruit good members.

In situations where our elected leaders are not developing laws and policies to address our current dilemmas, we must expand the number of people devoted to these problems and create supplementary mechanisms. We must create a sense of forward progress amidst cringe-worthy dysfunction and appoint new thought leaders to propel actionable ideas.

Weekly Insight State Government