Almost half of college students worry that they will run out of food before they get money to buy more.

Nearly half of college students can’t afford to eat balanced meals.

Almost 38% of college students cut the size of meals or skip meals because there’s not enough money for food.

These data, found in the recently-released National #RealCollege Survey report, paint a stark picture of hunger among college students in the United States — a reality that Mariá Paz understands all too well. Paz, who spoke with me at last year’s Real College convening in Philadelphia, never thought she would visit a food pantry. She moved from Honduras to Virginia and enrolled at Northern Virginia Community College with a budget and a plan. But then, her mother fell ill, and Paz’s plan fell apart.

She struggled to balance the financial demands of out-of-state tuition, housing, transportation, and food. She was forced to make tough choices — pay the bus fare to get to class, or buy groceries?

“Sometimes I had to give up transportation, or maybe I only ate the canned food from the pantry — high in sugar and sodium. Then when you don’t eat well, you don’t feel well, and then you don’t study well,” said Paz.

Her experience is just one of thousands of students at two-year and four-year colleges and universities that face food insecurity. But national data on food and housing insecurity among college students can be hard to come by. In a recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on food insecurity among college students, only 31 studies were analyzed, none of which offered national estimates.

One of the leading surveys on basic needs insecurities among college students, the #RealCollege Survey is administered by the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice at Temple University. Over the last four years, the center has surveyed roughly 167,000 students from 101 community colleges and 68 four-year colleges and universities. The center’s most recent report includes data from almost 86,000 students at 90 two-year colleges and 33 four-year institutions. The report also includes extensive data on housing insecurity and homelessness among college students.

While the report includes college and universities from numerous states, no institutions in North Carolina participated in the 2018 survey. Of the 101 community colleges included in the survey, 48 are in California. Of the 33 four-year institutions included in the survey, 12 are in New York.

How hungry are college students?

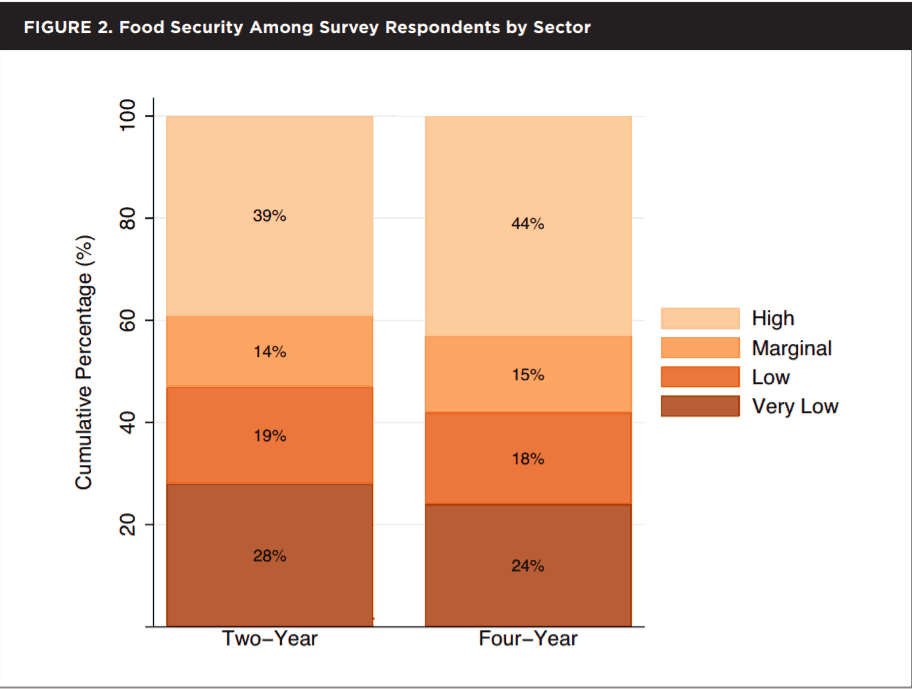

The report assesses food security among surveyed students using the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) set of 18 questions. The question set is used to determine if a student’s food security is high, marginal, low, or very low. The low and very low categories are considered “food insecure.”

The study found that rates of food insecurity are higher for students at two-year colleges compared to their peers at four-year colleges. During the month before the survey was taken, roughly 48% of students in two-year colleges experienced food insecurity, with 19% at the low level and 28% at the very low level. At four-year institutions, 41% of students experienced food insecurity, with roughly 18% at the low level and 24% at the very low level.

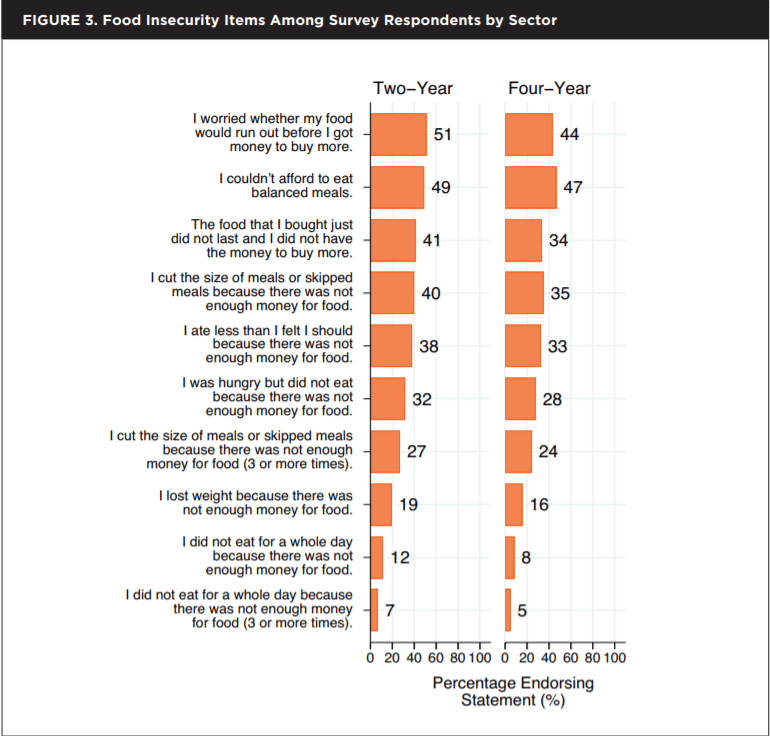

Digging a level deeper, the two most-endorsed statements in the questionnaire were “I worried whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more,” and “I couldn’t afford to eat balanced meals.” The chart below shows a breakdown of the percentage of students who endorsed each statement at the two-year and four-year levels.

And, there are demographic disparities in food insecurity across a variety of factors including race or ethnicity, first-generation status, sexual orientation, and gender orientation. Here are some of the demographic findings of the study:

- The rate of food insecurity among African American or black students is 58%, which is eight percentage points higher than the overall rate for Hispanic or Latinx students and 19 percentage points higher than the overall rate for white students.

- The rate of food insecurity among first-generation college students (those whose highest level of parental education is some college, a high school diploma, or no high school diploma) is roughly 50%, which is 18 percentage points higher than the overall rate for students whose parents hold a bachelor’s degree or greater.

- The rate of food insecurity among gay or lesbian students is 52%, which is eight percentage points higher than the overall rate for heterosexual or straight students.

- The rate of food insecurity among transgender students is 55%, which is eight percentage points higher than the overall rate for female students and 13 percentage points higher than the overall rate for male students.

Additionally, food insecurity varies among a variety of economic and academic factors, as well as life experiences. Working during college is not associated with lower rates of food insecurity, and neither is receiving the federal Pell Grant. Here are some of those findings:

- The rate of food insecurity for students who are considered independent from their families for the purposes of filing a FAFSA is 64%, which is 20 percentage points higher than students considered dependent.

- The rate of food insecurity for students receiving Pell Grants is 54%, which is 15 percentage points higher than those not receiving the grants.

- When it comes to employment status, the rate of food insecurity is highest among students who are employed, at 50%. Students who aren’t employed but are looking for work have a food insecurity rate of 47%, and unemployed students have a food insecurity rate of 31%.

One solution: Addressing the SNAP gap

As stated earlier, receiving Pell Grants and working while in college are not associated with lower rates of food insecurity — rather, the opposite is true. According to the GAO report, Pell Grants cover only 37% of tuition, fees, room, and board at two-year colleges, and just 19% of those fees at four-year colleges. Federal work-study payments are available to some students, but funding for those positions is limited, especially at two-year colleges. Faced with the reality that federal student aid isn’t enough to cover the basic needs of students, many colleges and students have shifted focus to leveraging other federal benefits.

The first line of defense against hunger in America is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, administered by the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) of the USDA. According to the USDA FNS website, “most able-bodied students ages 18 through 49 who are enrolled in college or other institutions of higher education at least half time are not eligible for SNAP benefits.” However, college students may qualify if they meet certain requirements, such as working at least 20 hours a week or taking part in a federal- or state-financed work-study program.

For many at-risk college students, it can be difficult or impossible to access federal benefits like SNAP due to a variety of factors, including eligibility requirements and a lack of information. This leaves at-risk college students trapped between two systems: free- and reduced-price meals designed to support K-12 students and SNAP benefits designed to support low-income individuals and families not enrolled in college.

The #RealCollege survey found that only 20% of food insecure students receive SNAP benefits. Similarly, the GAO report conducted an analysis of Department of Education data and found that almost 2 million at-risk students who were potentially eligible for SNAP did not report receiving benefits in 2016.

Closing this gap in public assistance between those facing food insecurity and those accessing SNAP is one strategy to addressing food insecurity among college students. The #RealCollege report includes this as one of its five recommendations, stating:

“Access to public assistance needs to be further expanded for college students. In particular, we must extend the opportunity to enroll in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to college students who work less than 20 hours a week or go to school part-time, and allow college enrollment and work-study hours to fulfill job-training requirements.”

The GAO report recommends that the FNS improve the eligibility information for college students on its website and that it share more information on state SNAP agencies’ approaches to helping eligible students. One example of a coordinated effort to connect more college students with public assistance is Single Stop, a national nonprofit operating in dozens of two- and four-year colleges and universities across the country. Read more about the impact of Single Stop’s work on community college persistence and completion here.

The other four recommendations in the #RealCollege report include:

- Appoint a Director of Student Wellness and Basic Needs

- Evolve programmatic work to advance cultural changes on campus.

- Engage community organizations and the private sector in proactive, rather than reactive, support.

- Develop and expand an emergency aid program.