Last weekend, I came across an old composition notebook with pages so yellow it looked like it could be from 1850. In it were various home remedies for different ailments, including one for appendicitis that suggested mixing timothy seed with boiling water and drinking it hot. After researching a timothy seed, I laughed at the thought of using it as a treatment for appendicitis.

It is hard to imagine using 19th century medical practices to treat something like appendicitis in 2017. Yet, this is how Patrick Cook-Deegan describes American high schools today – as institutions that are using 19th and 20th century practices to educate kids for the 21st century. This may have worked 100 years ago, but today’s high schools are as unprepared to educate kids for 21st century jobs as someone living in the 1850’s would be to treat appendicitis.

In a recent Stanford Social Innovation Review webinar, “Rebooting the American High School with Neuroscience and Purpose Learning,” Patrick Cook-Deegan and Bob Lenz explain why American high schools need to be redesigned for the 21st century and how project-based and purpose learning can help.

Our high school system was designed during the Industrial Revolution. Although society has changed greatly since then, our school system has largely remained the same. Cook-Deegan and Lenz point out that compared to elementary and middle school classrooms, high school classrooms are the least innovative. In many high schools today, students sit in desks in a classroom taking notes while a teacher lectures.

Neuroscience research determined years ago that this model does not work for adolescent brains. Research shows that forcing adolescents (defined as ages 12-24) to wake up as early as 6 a.m. to get to school by 7:15 a.m. is harmful to their learning. In addition, requiring high schoolers to remain seated for seven hours in a small classroom and absorb material is not conducive to learning.

Cook-Deegan and Lenz cite a recent survey of high school students where the top three words they used to describe high school were bored, tired, and stressed. Think about the last time you had to sit still for 7 hours straight with few breaks and listen to someone lecture — you probably felt bored, tired, or stressed. It is no wonder that the high school dropout rate is so high.

Future jobs require different skills than what high schools are teaching

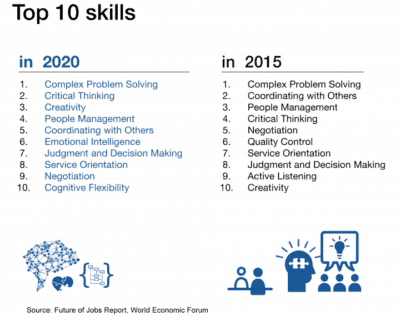

High school students are bored because what they are learning has very little connection to what they will be required to do in college or a future job. Cook-Deegan notes that to do well in high school, students need to be able to memorize and regurgitate information, work well on their own, be competitive, and work on many different things at the same time. On the contrary, to be successful in today’s job market, students need to be able to work well with others, be adaptable, and be creative.

The graphic below shows the top 10 skills workers will need in 2020, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Future of Jobs Report. Complex problem solving, creativity, and coordinating with others all fall within the top five skills, yet our current high school model does not teach these.

The Future of Jobs Report also states that 65 percent of today’s primary school students will have jobs that do not yet exist. How do we prepare students for jobs that do not exist?

Many experts, including Cook-Deegan and Lenz, argue that instead of solely teaching content, schools should also teach certain traits, such as problem solving, creativity, empathy, and collaboration. To do this, however, requires radically rethinking the traditional high school experience.

Cook-Deegan and Lenz have different solutions to the question of how we redesign high schools to prepare students for 21st century jobs. However, both are focused on making learning relevant to students and building student capacity to solve complex problems in the world around them.

Creating a sense of purpose in high school

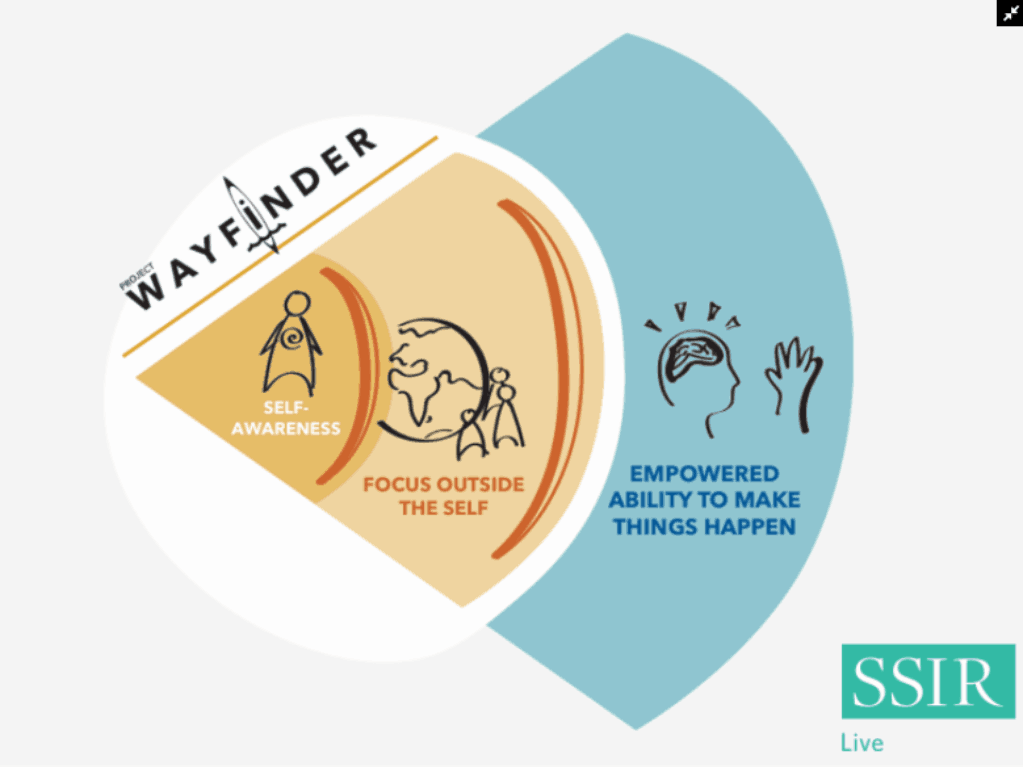

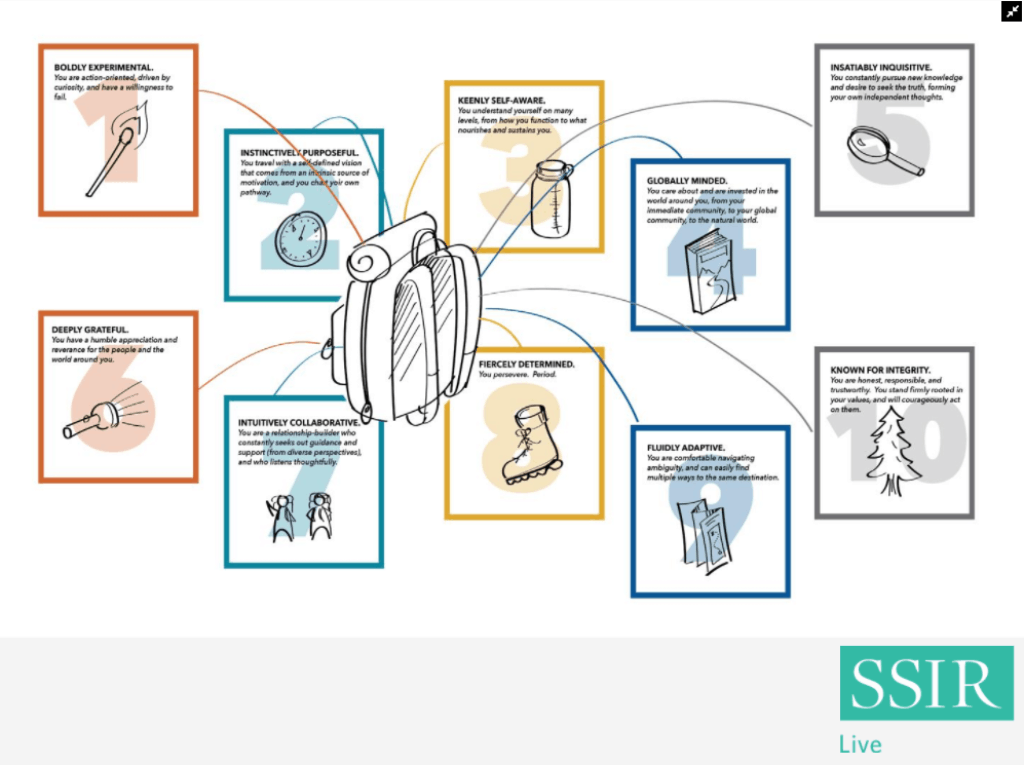

After teaching in high schools for years, Cook-Deegan founded Project Wayfinder, an organization dedicated to helping students create a sense of purpose in their lives. They created a curriculum that takes students through three stages from self awareness to focus outside of self to empowered ability to make things happen.

The goal of this curriculum is for students to understand their own identities and then understand the needs of their communities. Cook-Deegan believes that keeping high school students inside the walls of a school for 90 percent of the year does not prepare students to be involved in their communities once they leave. Project Wayfinder seeks to get students out in the world exploring their communities before they graduate high school.

To enable students to move through the third part of the curriculum, an empowered ability to make things happen, Project Wayfinder encourages students to learn by doing. Part of that includes learning through failure, which Cook-Deegan argues is a crucial skill that is not being taught currently. Instead, most high school students feel like one bad grade or one mistake can ruin their lives. Being fluidly adaptive is one of Project Wayfinder’s top 10 traits because students need to learn to take risks and not fear failure in order to succeed in college and careers.

Ultimately, Project Wayfinder wants to change high school students from “linear pathtakers” with a series of requirements to “self-reliant wayfinders” who move through a series of projects and opportunities with a defined sense of purpose.

Redesigning the high school experience with project-based learning

Bob Lenz believes project-based learning is key to equipping students for the 21st century. The problem, he says, is that the world has changed but high schools have not:

“The world is connected. It’s complex, it’s becoming automated, it’s project-based, it’s collaborative, and schools are not. Consequently, too many students, especially those furthest from opportunity, are unprepared to meet those challenges.”

Lenz began experimenting with project-based learning in the 1990’s as a high school teacher in Marin County, California. Teachers and leaders at his school decided to redesign their curriculum to focus on integrated project-based learning. Due to their success with this approach, his school was named a New American High School in 1999. They received substantial media attention and visitors who wanted to learn about project-based learning.

Because the student population at his school was middle-class and white, many visitors walked away saying that they could never do project-based learning with “their kids.” As Lenz describes, “their kids” usually meant low-income, minority students. To counter this belief, Lenz and others launched Envision Schools, where they used project-based learning to redesign high schools and prove that all kids could succeed with this approach.

What is project-based learning?

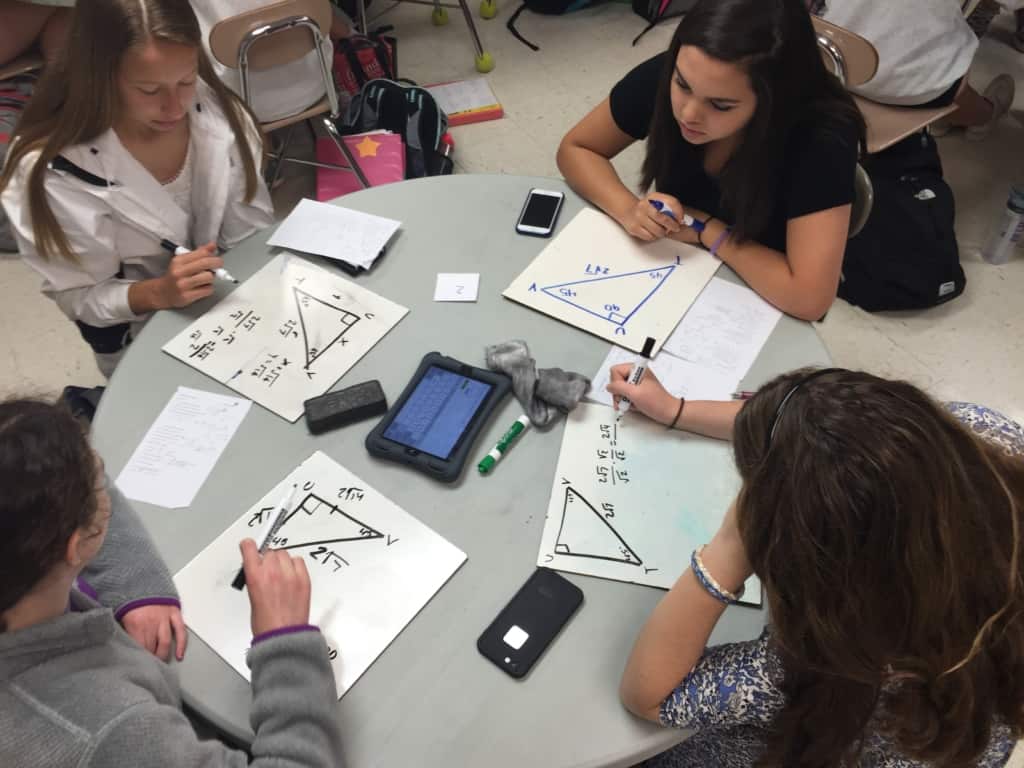

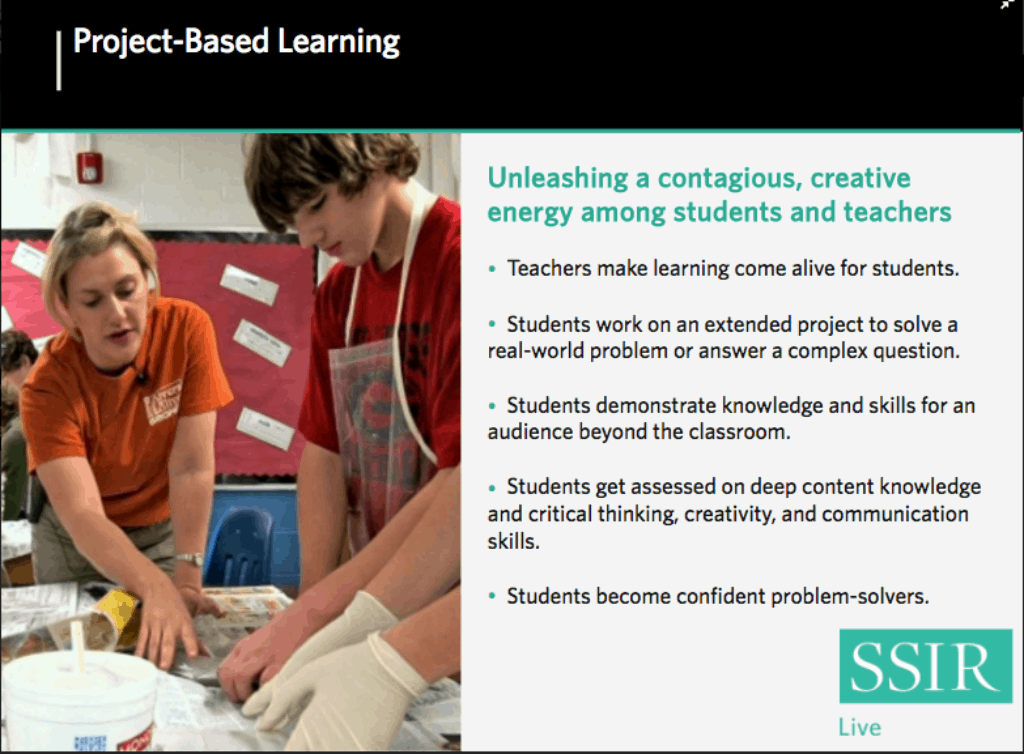

Project-based learning is not new, but too few high schools use it today. The slide below captures the core tenets of project-based learning according to Lenz.

Just as with Project Wayfinder’s curriculum, project-based learning teaches students to solve complex, real-world problems. In addition to knowing the required content, students are also required to collaborate with their peers, mimicking the reality of most 21st century jobs. Working on these projects teaches students many of the top 10 skills for future jobs listed above.

How can schools adopt project-based learning?

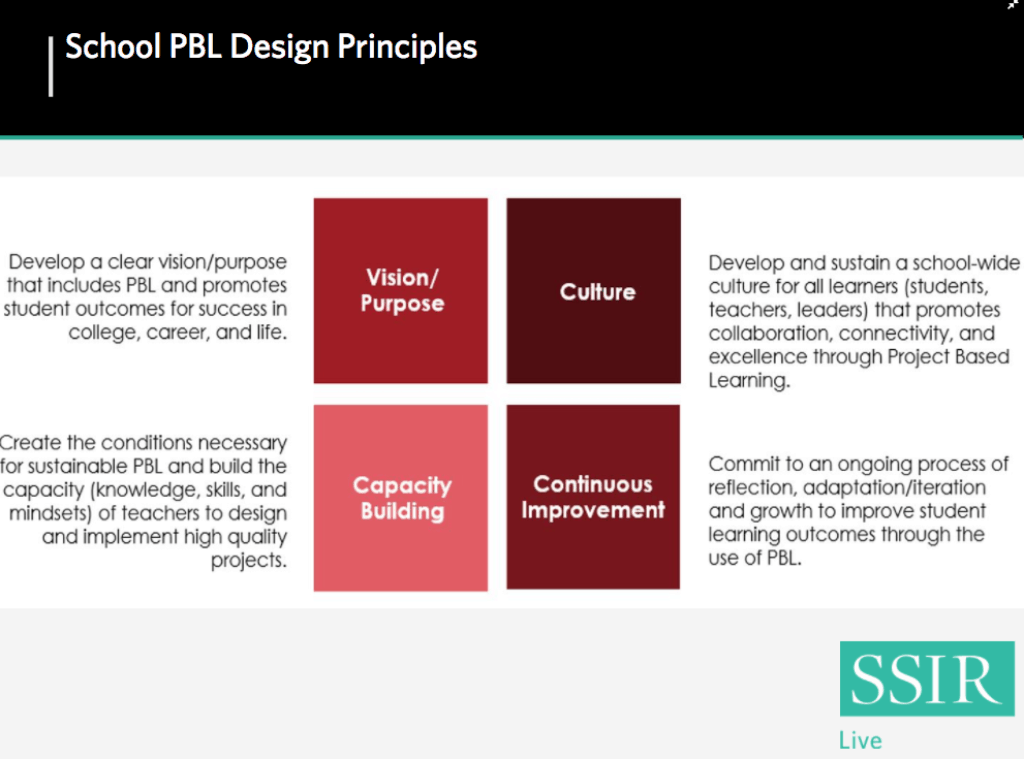

Simply redesigning the structure of high school classrooms is not going to create successful project-based learning. Lenz describes how building teacher capacity is critical to introducing project-based learning in any school; Teachers who have been trained to “stand and deliver” cannot be expected to know how to successfully integrate project-based learning in their classrooms.

Additionally, school and district leaders need to create the right conditions for project-based learning. When Lenz works with school leaders to implement project-based learning, he uses the following principles and encourages school leaders not to abandon project-based learning if they are not seeing results immediately. He estimates that it takes five to seven years to successfully redesign a school around project-based learning.

Evidence of success

The Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (SCOPE) studied four Envision Schools and found higher rates of student engagement, high school graduation, college acceptance, and college persistence at schools where 70 percent of students were low-income. One school, City Arts and Technology High School, had a 95 percent college persistence rate (the percentage of students who return to college for a second year). The national average college persistence rate for students starting college in 2015 is 61 percent.

These results demonstrate that project-based learning is not just for white, middle-class students but can be successful at any school. As we look to the future of education in North Carolina, purpose learning and project-based learning need to be included in the conversation.

Thanks to the Stanford Social Innovation Review, you can view the slides below and register for the webinar on their website.