Opening in 1856, Dorothea Dix Hospital was in continuous operation until its controversial closing in 2010.

The following excerpt is part of a larger study originally published in a special North Carolina Insight report on the History of Mental Health Reform in North Carolina in March 2009. You can read the full report here

“Historical knowledge can deepen the way in which we think about contemporary issues and problems. It can also sensitize us to the dangers of simplistic solutions.”—Gerald N. Grob, Ph.D.

Despite the efforts of several North Carolina governors in the 1820s and 1830s to make care of the mentally ill a legislative priority, North Carolina was next to last among the original 13 colonies (the last was Delaware) to enact legislation for the establishment of a state asylum.24 In an oft-repeated pattern, the early governors’ efforts to address the needs of the mentally ill simply resulted in an abundance of studies with few tangible results.

“Whereof what’s past is prologue, what to come In yours and my discharge.” — William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Initially, an 1825 resolution called upon two members in the legislature to collect information and report a plan for the creation of “a lunatic asylum.”25 In 1827, a joint legislative committee reviewed the resulting report and recommended another report.26 While recognizing that it would “add luster to a government . . . to protect and cherish the unfortunate individual who by the visitation of God has been deprived of his reason,” the joint committee feared that the costs of constructing an asylum would be too high and sought a study of the feasibility of establishing a penitentiary and asylum as one institution.27 No other action was taken for the next 10 years until the closing month of the 1838-39 legislative session when another resolution was passed, in connection with a resolution seeking information about a penitentiary and an orphans’ home, seeking information on the number of insane in North Carolina, whether they were “‘at large or in confinement and where and how long confined.’”28

“Health organization and policy never arise anew. They evolve from prior culture and understandings, health care arrangements, health professional organizations, and political and economic processes.”—David Mechanic, Ph.D.

Five years later, in 1844, in response to Governor John Motley Morehead’s recommendation that North Carolina establish asylums for the insane, blind, and deaf, the legislature appointed yet another special committee which subsequently recommended that money from the Internal Improvements Fund be used to establish the asylums.29 The report noted that there were “801 insane persons and idiots in North Carolina in 1840” and urged the legislature to remove them from their “cold and noisome cells where they had been shut up ‘to drag out the miserable remnant of their days, without fire to warm their benumbed limbs . . . and without friends . . . to soothe and calm the tempest raging within their distempered imaginations.’”30 No legislation passed, however, because the legislature was unwilling to tamper with the Internal Improvements Fund and incur the wrath of the voting public by imposing a tax to raise the necessary funds.31

Another five years passed before North Carolina finally enacted a law for the establishment of an insane asylum at the urging of Dorothea Dix, a crusader for the humane treatment of the mentally ill and ardent advocate of the asylum system.32 In November 1848, Dix presented a “Memorial Soliciting a State Hospital for the Protection and Cure of the Insane” to the North Carolina General Assembly asking for “an adequate appropriation for the construction of a Hospital for the remedial treatment of the Insane in the State of North Carolina.”33 In this Memorial, Dix provided a county by county assessment of the often inhumane treatment of the mentally ill. As Dix noted,

At present there are practiced in the State of North Carolina, four methods of disposing of her more than one thousand insane, epileptic, and idiot citizens, viz: In the cells and dungeons of the County jails, in comfortless rooms and cages in the county poor-houses, in the dwellings of private families, and by sending the patients to distant hospitals, more seasonably established in sister States. I ask to represent some of the very serious evils and disadvantages of each and all these methods of disposing of the insane, whether belonging to the poor or to the opulent classes of citizens.

It may be here stated that by far the larger portion of the insane epileptics, and idiots, are detained in or near private families, few by comparison, being sent to Northern or Southern State hospitals, and yet fewer detained in prisons and poor-houses, yet so many in these last, and so melancholy their condition, that were the survey taken of these cases alone, no stronger arguments would be needed to incite energetic measures for establishing an institution in North Carolina adapted to their necessities, and to the wants of the continually recurring cases, which each year swell the record of unalleviated unmitigated miseries.34

Dix appealed to the hearts, minds, and pocketbooks of the state legislature noting that the costs of treating, and in many instances curing, the mentally ill in state hospitals was 32 times less expensive to the state or local coffers than leaving them untreated in either poorhouses, jails, or other unsuitable environments.35

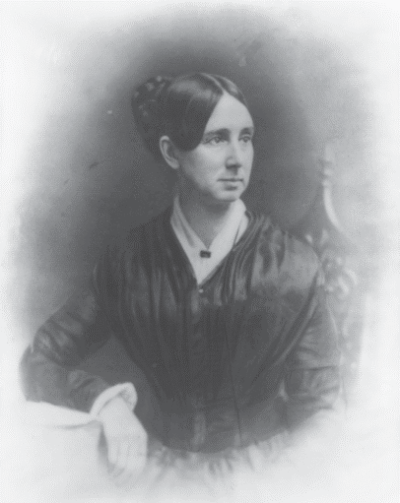

Dorothea DixDorothea Dix, born April 4, 1802, was a teacher, nurse, and famous advocate for the mentally ill in the United States. After a childhood spent with her grandmother in Worchester and Boston, Massachusetts, she opened and taught at two schools from age 14 through 19 before she went abroad in 1836 to improve her tubercular medical condition. Her passion for teaching continued when she returned two years later. In 1841, she began her research and advocacy for the improved treatment of the mentally ill in asylums. Dix taught a Sunday school lesson for some women inmates in the Cambridge, Massachusetts jail. She insisted on touring the facility, where she witnessed “miserable, wild and stuporous men and women chained to walls and locked into pens-naked, filthy, brutalized, underfed, given no heat, sleeping on stone floors. It was this visit that started Dorothea on her life’s work to improve conditions for the mentally ill.” Dix proceeded to travel around the country, as well as to other countries, to research the conditions of the mentally ill, report them to the various levels of government, and push for legislation based on what she found. In the late 1840s, the state of North Carolina had done very little in the way of creating hospitals or other space for those who needed services for chronic mental illness, despite recommendations from several state officials in the 1820s and 1830s. Dorothea Dix made her historic trip to North Carolina in 1848, where she “followed her established pattern of gathering information about local conditions which she then incorporated into a ‘memorial’ to the General Assembly.” She described the situation for people with mental illness: “In Lincoln County, near a public road… is a log cabin strongly built and about 10 feet square, and about seven or eight feet high; no windows to admit light… no chimney indicates that a fire can be kindled within, and the small low door is securely locked and barred… You need not ask to what uses it is appropriated. The shrill cries of an incarcerated maniac will arrest you on the way… Examine the interior of this prison [and] you will see a ferocious, filthy, unshorn half-clad creature, wallowing in foul, noisome straw. The horrors of this place can hardly be imagined; the state of the maniac is revolting in the extreme….” In Raleigh, she found emotionally disturbed persons locked in jails or living on the streets. She faced a tough audience with the legislators who did not wish to spend large sums of funding on the mentally ill. By coincidence, in the midst of negotiations on the failed bill, Dix went to the aid of a fellow guest at the Mansion House Hotel in Raleigh, Mrs. James Dobbins, and nursed her through her final illness. Mrs. Dobbins’ husband was a leading Democrat in the House of Commons, and her dying request of him was to support Dix’s bill. James Dobbins returned to the House and made an impassioned speech calling for the reconsideration of the bill.” The General Assembly reconsidered the bill, and the legislation became law. After 100 years of operation, the name of the original 1856 hospital resulting from Dix’s legislative efforts was changed from the Dix Hill Asylum to the Dorothea Dix Hospital. sources: http://www.dhhs.state.nc.us/mhddsas/DIX/dorothea.html; http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/jan2006/index.html |

In an impassioned speech delivered in the North Carolina House of Commons in December 1848, Kenneth Rayner of Hertford, articulated the moral treatment view- point with respect to the state’s responsibility for caring for her mentally ill citizens:

The object of government is to take care of all. And the Representative of a confiding and generous people can perform no more welcome task, than that of providing for a mitigation of one of the most awful calamities visited upon our race. . . . Until within the period of the existence of our own government, young as it is, the old plan of the dark ages . . . of treating the insane as outcasts, was the only one known. The dark and noisome cell, the chain and the hand cuff, the bar and the bolt, lash and the torture, the scanty meal and the time-worn vesture, were, for ages, the portion of these victims of misfortune. This cruel system, and the false idea upon which it rested, are now, and it is hoped, forever rejected, as unwise, unfeeling, unchristian. . . . [In properly treating the mentally ill], you must resort to comparatively isolated locations; you must obtain the services of those who devote their lives exclusively to this noble and praise worthy vocation, you must congregate those unfortunate victims, where time, opportunity, knowledge, and experience can all be commanded in ministering to their wants. 36

Although nearly defeated “amid political and financial brawls,” the legislation passed on a reconsideration vote on January 29, 1849, after James C. Dobbin, a political leader and member of the legislature “brought up an amendment to the original bill and in a great emotional speech united Whigs and Democrats to obtain passage of the measure.”37 Dobbins’ wife, who had been visited and cheered by visits from Dix as she lay dying, had urged her husband on her deathbed to support the legislation.38 The Raleigh Register described Dobbin’s speech as “one of the most touchingly beautiful efforts that we have ever heard.”39

Construction of the North Carolina Insane Asylum in Raleigh was finally completed at a site, named Dix Hill in honor of Dix’s father, in 1856.40 Before the turn of the century, two additional psychiatric facilities had been approved and built in North Carolina. Broughton Hospital in Morganton, which serves the 27 westernmost counties, admitted its first patient in 1883.41 Goldsboro’s Cherry Hospital was named the “Asylum for the Colored Insane” when it opened in August 1880. Until the implementation of the Civil Rights Act 85 years later, this hospital served the entire black population of the State of North Carolina. It served 33 eastern North Carolina counties until its closing.42

See the full PDF of the report here