The impact of teachers on educational attainment is well-researched, and policy discussions often focus on recruiting, preparing, and retaining effective teachers in the classroom. “When it comes to student performance on reading and math tests, a teacher is estimated to have two to three times the impact of any other school factor, including services, facilities, and even leadership,” reads a RAND briefing on the impact of teachers.

Teachers matter. And a new working paper out of Harvard suggests that effective school counselors matter just as much as teachers — if not more — when it comes to educational attainment. The paper, written by Christine Mulhern, provides the first quantitative evidence of counselors’ effects on a variety of outcomes, including high school graduation, college attendance, selectivity, and persistence.

As North Carolina works towards its postsecondary attainment goal set by myFutureNC — 2 million 25- to 44-year-olds with a high-quality credential or college degree by 2030 — this research provides a case for improving access to effective counselors.

What’s the role of school counselors?

Think back to your high school experience. Who helped you navigate decisions like which courses to take or which electives to explore? Who shared information with you about how to navigate postsecondary education and career opportunities after graduation day? These and other decisions facing high school students are complex — and that’s where school counselors come in to play.

High school counselors wear many hats, from providing assistance on course scheduling to college and career advising to other general support for students. Mulhern identifies four main ways that counselors are likely to influence students’ educational attainment: cognitive skills (placing them in or removing them from certain classrooms), non-cognitive skills (behavior and mental health counseling), information (about postsecondary education and career options), and direct assistance (providing things like accommodations, SAT fee waivers, letters of recommendation, and more).

Depending on the availability of school psychologists and college counselors, school counselors may have varied roles across school and districts. During a presentation to North Carolina’s House Select Committee on School Safety in 2018, representatives from the North Carolina School Counselor Association described counselors as being on the “front lines of mental health issues in schools” and discussed their impacts on socio-emotional skills, cognitive skills, and career and college readiness.

A closer look at the study

In some Massachusetts high schools, students are assigned to school counselors based on the first letter of their last name, and those assignments may change over time and across schools based on the number of counselors available and the distribution of student names. Using this as a framework, Mulhern estimates the impact of a student’s first assigned counselor on his or her outcomes after controlling for a variety of factors, including the first letter of the student’s last name, year, school, demographics, and eighth grade test score.

Here are some of the key findings from the paper.

Finding 1: Counselors vary significantly in their influence on high school graduation, college enrollment, selectivity, and persistence.

Within schools, counselors vary significantly in how much they affect educational attainment. The standard deviation of counselor effects on college persistence is 1.1 percentage points — meaning that students assigned to a counselor who is one standard deviation above average on this metric are 1.1 percentage points more likely to persist in college. The standard deviation of counselor effects on high school graduation and four-year college attendance are roughly 2 percentage points.

Counselors also impact student experiences while still in high school. For example, assignment to a counselor who is one standard deviation better increases a student’s probability of taking the SAT by roughly 4 percentage points, and counselors also influence AP test taking. On the other hand, students assigned to a counselor who is one standard deviation below average are almost 3 percentage points more likely to be suspended than students assigned to the average counselor.

Mulhern also finds that counselors influence the types of colleges that students attend, including whether a student attends a selective college, the graduation rate at the college a student attends, and whether the student majors in a STEM field. And, ninth grade counselors have a larger effect on high school graduation than counselors in later grades, while 12th grade counselors have the largest effects on four-year college enrollment and the graduation rate of the college a student attends.

Finding 2: Counselors matter most for low-achieving and low-income students.

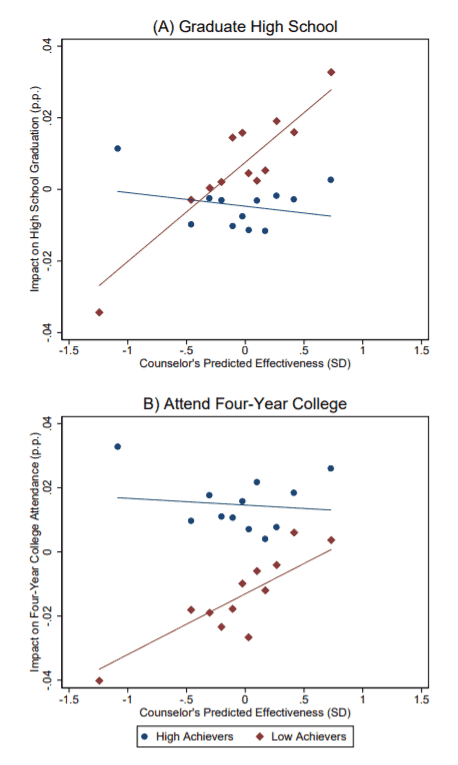

Mulhern finds that counselor effectiveness is more predictive of low-achieving student outcomes than those for high-achieving students. A one standard deviation better counselor increases high school graduation for low-achieving students by 3.4 percentage points and college attendance by 2.5 percentage points. And, low-achieving students see an 8% increase in four-year college attendance and a 6% increase in persistence from a more effective counselor. In contract, counselors have no significant effects on these outcomes for higher achieving students.

Similarly, counselor effectiveness matters more for low-income students (determined by free- and reduced-price lunch status) than for their peers. Low-income students with a counselor that is one standard deviation better are 3.4 percentage points more likely to graduate high school than students assigned to an average counselor, and they are 8% more likely to attend a four-year college.

Low-achieving and low-income students are often on “the margin of completing high school and attending college” and are less likely to have access to social networks with college information, making counselors’ large effects on them that much more important. Mulhern writes: “These results indicate that counselors may be an important resource for closing socioeconomic gaps in education.”

Finding 3: Counselors’ effects on attainment are driven by the information and assistance they provide to students, rather than improving their cognitive or non-cognitive skills.

The positive impact that counselors have on attainment is driven primarily by counselors connecting students to information and providing direct assistance that increases college readiness and selectivity, emphasizing the important role counselors play in access to opportunities. For example, counselors might have a large impact on students taking the SAT by providing information about test dates or obtaining fee waivers for students. In contrast, Mulhern finds little variation in the effect of counselors on students’ cognitive skills, such as GPA or 10th grade test scores.

Finding 4: Students benefit from being matched to a counselor of the same race and from having a counselor who attended a local college.

Students who were assigned to a counselor of the same race are about 2 percentage points more likely to graduate high school, attend college, and persist than those who were assigned to a counselor of a different race. When only considering non-white students, these effects increase to 3.8 percentage points. “Minority counselors may know more about the unique hurdles faced by minority students in college access and the types of colleges which are likely to be the best fit,” Mulhern writes. This finding is in keeping with research on the benefits students receive when matched with a teacher of the same race, except Mulhern finds that white students also benefit from same-race matches with counselors.

When it comes to education, the college a counselor attended is predictive of whether and where his or her students attend college. Students assigned to counselors who received a bachelor’s degree in Massachusetts were 2.5 percentage points more likely to graduate high school than those assigned to a counselor with an out-of-state degree. Mulhern writes that “these counselors may have a better understanding of the local college options, the needs of local students, or state graduation requirements than counselors educated elsewhere.”

Finding 5: Reducing the caseload of counselors is unlikely to yield larger benefits than improving access to effective counselors.

After controlling for student or school characteristics, the negative association between larger student caseloads and students outcomes disappears. Mulhern finds that hiring an additional counselor in every Massachusetts high school would increase high school graduation and four-year college attendance by roughly half as much as increasing counselor effectiveness by one standard deviation.

Mulhern continues by discussing the fact that the magnitude of counselor effects on attainment are in the same range as teachers’ effects, pointing out that teachers are not the only important educators and that counselors can have similar long-term effects as teachers.

“Given the significant attention and resources devoted to teachers and improving teaching, additional attention may be warranted for counselors. Furthermore, improving the effectiveness of one counselor can impact many more students than improving the effectiveness of one teacher because counselors serve many students,” Mulhern writes.

North Carolina context

As of 2018, the ratio of school counselors to students in North Carolina was 1 to 386. The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 1 to 250, lower than the ratio in most states. According to the North Carolina School Counselor Association, having one full-time school counselor in every North Carolina public school would move the state closer to the recommended ratio of 1 to 250.

House Bill 75, which was signed into law during the 2019 legislative session, requires the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) to study and report on school psychologist and school counselor positions. The study will include things like:

- The number of school counselor positions in the state and in each district;

- The allocation of school counselors among schools in each district;

- The way that districts determine the allocation of school counselors;

- The geographic density of school counselors;

- The number, percentage, and average salary of school counselor positions funded with state and non-state dollars;

- The extent to which districts provide school counselors with local salary supplements and the amount of those supplements;

- And the job descriptions posted for school counselors compared to the actual duties of school counselors.

DPI has to report the results of the study to the Joint Legislative Education Oversight Committee and the Fiscal Research Division no later than April 1, 2020.

One bright spot when it comes to school counseling in North Carolina is Carolina College Advising Corps, a program that places recent college graduates as college advisors in high schools across the state to help low-income, under-represented, and first-generation college students apply and enroll in college. On average, corps partner schools had an average 10-11% increase in college enrollment within the first year of the partnership. And, roughly 74% of corps students who enrolled in college return for their second year, which is higher than the national average of 69% for low-income students.

Weekly Insight Education