On July 6, North Carolinians had a first look at the future of North Carolina’s Achievement School District, a controversial education reform with the goal of turning around the state’s lowest performing schools.

At the State Board of Education meeting, Dr. Eric Hall, the newly appointed superintendent of the Achievement School District, gave his first presentation, detailing his vision for the upcoming district. Modeled after similar districts with mixed results in Tennessee and Louisiana, legislation creating the Achievement School District was passed during the 2016 General Assembly short session.

The Achievement School District measure created two changes.

First, it created a separate “district,” now called the Innovative School District, comprised of no more than five low-performing schools from across the state. The State Board of Education selects operators to run the five ISD schools, including charter operators. These operators will be required to meet the same requirements as charter schools which differ in their regulations from traditional public schools. They have no curricular requirements, class size restrictions, can modify their calendar, and only 50 percent of teachers are required to be licensed.

Secondly, the bill gave districts that have at least one school in the ISD the option of creating an innovation zone in their district for up to three additional low performing schools. These schools are operated by the local district but are given the same flexibilities and exemptions from state and local policies as charter schools.

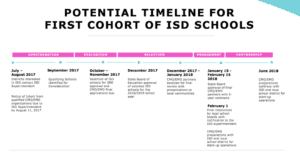

According to Dr. Hall’s presentation timeline, the first cohort of ISD schools could be identified in September and approved by the Board in December. If one of their schools is selected for the ISD, districts could begin planning for an innovation zone as early as this fall.

The idea of innovation zones is not new but is gaining momentum in the wake of backlash against state and charter takeover of failing schools. The city of Memphis has succeeded in their turnaround efforts under a locally controlled Innovation Zone, proving that local school districts can turn around their own schools, using their own staff, teachers, and principals. The Memphis experience offers guidance for North Carolina’s efforts.

Memphis’ Innovation Zone: Background

The Memphis’ Innovation Zone (iZone) was created in 2012 in response to Tennessee’s efforts to turn around the bottom five percent of schools in the state. Memphis hosted 69 of 85 schools in the bottom five percent of schools.

The Memphis school district – Shelby County Schools – created a turnaround initiative to avoid state takeover under the newly created Achievement School District. Starting with 16 schools in 2012, the iZone expanded to include 21 schools in 2017 educating more than 10,000 students in Memphis. The goal of the iZone is to move schools from the bottom five percent in the state to the top 25 percent in five years.

The iZone operates as a mini-district within Shelby County Schools. It is led by Chief of Schools Sharon Griffin and supported by a dedicated team of coaches within the district.

iZone principals are given more autonomy over staffing and curriculum than in traditional public schools, and all iZone schools have an extended school day. Teachers receive additional compensation for the extra hour and can receive performance bonuses, allowing principals to recruit the best teachers. If a principal does not feel like a teacher is a good fit for the school, she can remove that teacher at any point during the year – a process which would take much longer in a non-iZone school.

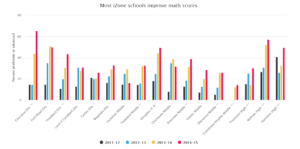

The iZone gained national attention after researchers at Vanderbilt University published a study in 2015 concluding that iZone schools were outpacing the state’s Achievement School District in test score growth.

The study found that while students in ASD schools were performing relatively the same as their peers in non-ASD schools, students in iZone schools in Memphis were significantly outperforming their peers in reading, math, and science.

Since its inception in 2012, seven schools have improved enough to be removed from the state’s priority list (bottom five percent) with 11 others making double-digit test score gains.

Lessons Learned

My graduate school colleague Jake Taylor and I visited the iZone in January 2017 and interviewed more than 25 principals, teachers, and Shelby County Schools administrators, including Dr. Griffin.

Our findings show reasons for the iZone success:

- Human capital is the most important factor in turning schools around

- Staffing and budgeting autonomy allows principals to meet student needs

- Dedicated support staff are crucial to success of the iZone

- A clear accountability system keeps teachers, principals, and district staff aligned towards benchmarks

1. Human capital is the most important factor in turning schools around

“Without high quality teachers, an iZone school can’t be successful.” – iZone principal

The biggest takeaway from visiting the Memphis iZone is that it takes exceptional leaders and teachers to turn around the lowest performing schools. When a school is turned over to the iZone, Dr. Griffin conducts a thorough interview process to select the principal for each school. The principals then choose their entire staff. Teachers who worked at the school previously may reapply for their jobs, but only those teachers who have a teacher rating of 4 or 5 (the highest ratings) may work in an iZone school.

Dr. Griffin described human capital development as the biggest lever of change but also the most challenging.

Administrators and principals alike said not everyone is equipped to be an iZone school leader or teacher. Principals and teachers have more autonomy in the iZone to make their own choices, but not everyone is capable to embrace that autonomy fully. “With empowerment comes great responsibility,” Dr. Griffin said. “I have to make sure my principals are ready to choose what they need.”

2. Staffing and budgeting autonomy allows principals to meet student needs

“I have the people with the same vision and mindset that I was looking for. I made the hiring based on the needs that I was seeing in the building.” – iZone principal

Principals cited staffing and budgetary autonomy as the two most important added flexibilities in the iZone to increase student achievement. Without these, they did not feel they could meet students’ needs as effectively.

Because great teachers are so essential to turning around under-performing schools like those in the iZone, the ability for principals to hire their own staff is crucial to their success. Staffing autonomy allows school leaders to create a teaching team best fit for their specific students.

iZone principals may remove a tenured teacher based on fit, ensuring that every teacher on staff shares the school’s mission to significantly increase student learning. The collective bargaining power of teachers in Tennessee is limited, but it can take several years to remove an under-performing tenured teacher from a traditional public school. Furthermore, it is not possible to fire a tenured teacher if they are negatively affecting school culture.

iZone principals and teachers all agreed that teaching at their schools is “not for everyone,” and in order to be successful, it is critical that every teacher be equally invested in the school’s mission. School leaders unanimously cited the ability to make staffing decisions based on instructional quality, student needs, and mission alignment as the most important autonomy they had.

Budgetary autonomy goes hand in hand with staffing autonomy. If schools are able to allocate their resources as they see fit, they can better meet student needs.

In the iZone, the main source of budget autonomy is through the federal School Improvement Grants (SIGs). All iZone schools can apply for SIGs, and selected schools receive an average of $450,000 per year, varying according to the number of students and needs of the school.

Most principals said they used their SIG money primarily to pay teachers for the extended school day, and if they had any leftover funds, they used those to hire additional teachers and coaches, invest in technology, or purchase curriculum. Other than the leftover SIG funding, however, iZone principals have limited control over their budget and would benefit from more control over how resources are allocated in their schools.

3. Dedicated support staff are crucial to success of the iZone

“We have iZone coaches who go into the schools and determine where support is needed, and they really give heavy support to those schools of need. They may even go in and help teach.” – iZone principal

iZone schools have teams of coaches, instructional leaders, and Dr. Griffin available daily to provide support, analyze data, and work with them to make sure their students are learning. This support includes weekly principal meetings, coaching for both principals and teachers, and providing teachers with instructional resources.

The iZone also works with school leaders on how to use their staffing and curriculum autonomy more effectively. For example, one first-year iZone principal described how he was paired with a veteran iZone principal to help him think about staffing needs and school culture during his first year in the iZone.

This model of intensive support is not necessary for all schools. Ford Road Elementary, an iZone school in its fifth year, receives much less direct support and coaching because of the large gains their students have made. Schools receive support based on their need, and so far this model has proven successful – although expensive.

As Dr. Griffin described, hiring coaches is one of the biggest expenses of the iZone, but she believes it is one of the most effective strategies to help struggling schools. Most iZone teachers and principals agreed.

4. A clear accountability system keeps teachers, principals, and district aligned

“Our expectations had to be different for this environment – no excuses for excellence. You have to have that grit to do this type of work. You have to know that what you’re doing makes a difference.” – iZone principal

The iZone was created to improve student achievement, not maintain the status quo. For this to happen, students need to make dramatic gains every year.

Dr. Griffin and her team work with school leaders to create benchmarks for each school, and then provide support throughout the year in analyzing data and improving teaching to reach those benchmarks. Multiple principals described how Dr. Griffin and her team knew their data inside and out and would check in weekly on students’ progress.

If schools fail to make gains, Dr. Griffin is not afraid to replace principals or work with principals to replace teachers. Since the start of the iZone in 2012, Dr. Griffin has replaced five principals due to performance.

Teachers know that they must show up every day ready to teach and help students learn. As one principal said, “iZone teachers operate with an urgency because they know they need to get results.”

Dr. Griffin described her philosophy of accountability as one of tiered empowerment; principals have more autonomy, but they are held accountable for results. So far, this model seems to be working.

Limitations of the iZone Model

While the iZone has been hailed as a successful alternative to state takeover of under-performing schools, there are a few limitations to this model.

The first is the cost. Extending the school day by an hour, paying for teacher bonuses, and paying for the iZone support staff is not without cost. Much of the money for the extended day has come from federal School Improvement Grants, but those only last for three years. For iZone schools that started in 2012, the funding ran out last year, and the district has been paying for the extra hour since then despite budget shortfalls. Dr. Griffin has been able to raise outside support, but it is uncertain how long that will last.

In response to the prohibitive cost, the district launched the Empowerment Zone last year with five schools. The model is similar to the iZone but without the extended school day.

The second limitation is the loss of high quality teachers in the rest of the district that results from the best teachers moving to the iZone. Dr. Griffin recognized this as a limitation and said that they are working on how to develop more talent in their teacher population. However, she was unapologetic about the fact that the lowest performing schools need the best teachers.

Conclusion

As North Carolina moves forward with the Innovative School District, districts should take advantage of the opportunity to create their own innovation zones. While they may not have the resources and district support staff to implement as extensive a model as the Memphis Innovation Zone, they can learn from its success and use it as an example of what is possible when districts invest in under-performing schools.

Weekly Insight