The scales of Lady Justice always have required the balancing of competing interests.

This week, the long-awaited and much-anticipated report by WestEd in collaboration with the Learning Policy Institute and the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation was released to the public (thanks to the reporting of EdNC’s Alex Granados). It’s 287 pages, and there are 12 supplemental research reports (note that a 13th report on early childhood is published within the report itself as Appendix E). Molly Osborne and Carol Bono on the EdNC team quickly produced this table of findings and recommendations.

“The future of the state hangs in the balance,” says the report. And later, “Children of North Carolina deserve better.”

North Carolina Constitution, Article I, Section 15. Education. The people have a right to the privilege of education, and it is the duty of the State to guard and maintain that right.

So here we are, North Carolina. The WestEd report and forthcoming consent decree (or decrees) give us a way to structure our conversations and debate about education as we head into 2020, balancing our past and our future, our costs and our return on investment, evidenced-based strategies and innovation.

Our past and our future

“Imagine going to school and having classes in the hallway, the cafeteria, or even a closet. The lighting is inadequate, making it difficult for you to see your textbook. The plaster walls that define your learning space are cracked, and the paint on them is peeling. Overhead, you can see some rusting pipes, and sometimes the roof leaks when it rains. In your science classroom, there aren’t enough microscopes much less the measuring devices, sinks, and safety equipment needed for experiments. Many of your textbooks are outdated, and sometimes you have to share your workbook because there aren’t enough to go around.

On the other hand, imagine going to school in a newer facility with dependable heating and air conditioning. Lots of courses are offered: calculus, advanced biology, chemistry, and physics, several foreign languages, journalism, as well as creative writing. There are plenty of desks, blackboards, and textbooks, plus many state-of-the-art computers that can be checked out overnight. The media center has audiovisual equipment that you can use to produce your own videos for special projects; the chemistry lab has many high-tech instruments, including digital read-out balances; the library has more than 26,000 volumes; the art department has a kiln, a press, and extensive art supplies; there is a publishing center — complete with an up-to-date graphics department where the school newspaper is printed. Classes are smaller, so your teachers have more time to help you.

Although it is hard to imagine that schools could be so different, these schools are not hypothetical. They are composite descriptions of schools across North Carolina.”

I wrote that back in 1996 based on my own visits to schools across the state and the affidavits of Purnell Swett, superintendent of the Public Schools of Robeson County; Willie Gilchrist, superintendent of Halifax County Schools; A. Craig Phillips, superintendent of Vance County Schools; Bill Harrison, superintendent of Hoke County Schools; and John Griffin, Jr., superintendent of Cumberland County Schools. The affidavits had been filed on Sept. 26, 1994 as part of the plaintiffs’ amended complaint in Leandro v. State.

As I scanned the WestEd report for the first time, these paragraphs on pages 11-12 did more than catch my attention — and not just because Gov. Jim Hunt happened to be sitting across the room from me:

“As was true throughout the nation, the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the 1965 Elementary and Secondary School Act together had a major impact on public education in North Carolina, leading to the racial integration of the schools and a major increase in federal involvement and funding for improving schools. The 1960s and 1970s also witnessed in North Carolina the advent of universal kindergarten, the 180-day school year, regional education support agencies, statewide testing, the requirement to provide appropriate educational opportunities for students with disabilities, the establishment of the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, the expansion of the UNC system, and many other policies and programs that formed a strong foundation for continued progress of the state’s system of public education.

That progress continued during the 1980s and 1990s when, with leadership from Governor James B. Hunt, Superintendent Bob Etheridge, and members of the General Assembly, North Carolina moved its education system forward in many ways. These advancements included establishing a new system of curriculum standards and assessments, strengthening the teaching profession, increasing funding for education, and implementing other initiatives that led to substantial increases in students’ achievement from the early 1990s through the mid-2000s. As a result, North Carolina became widely recognized nationally as a leading state for educational innovation and effectiveness.”

But near the height of the perception of our state as a national leader in education as described in the WestEd report, Leandro was filed in 1994 after almost 100 years of Democratic leadership. The unanimous N.C. Supreme Court decision establishing a constitutional right to a sound, basic education was handed down in 1997.

It has always been difficult — both historically and in the present day — to reconcile the perceptions of North Carolina’s education system and its realities.

What is clear to me from visiting schools then and now is that the challenges we face in providing a sound, basic education as our state constitution requires or the 21st century education our economy of tomorrow requires didn’t begin with the Great Recession or the political shifts of 2010.

Our system of education wasn’t good enough in the 1990s. It isn’t good enough now.

And though our challenges are not new, we do need a new way forward. The WestEd report is titled, “Sound Basic Education for All: An Action Plan for North Carolina.” Let’s start there. With all.

A colleague asked me the night the report was issued why a bipartisan approach matters.

Here’s one. Jeremy Anderson, president of Education Commission of the States, says in states where leaps and bounds are being made, leaders have found ways to work across difference. “It’s a simple litmus test,” he says. “Can the people who can move this policy meet for coffee even if they disagree and talk through some of these differences?”

Here’s another. We need solutions for all of our students, all of our teachers, in all of our schools, in all of our districts — and that means in our 23 counties that voted 70% or more for President Trump, in our urban blue crescent, and in the rest of our very purple counties.

North Carolinians, in my experience, don’t like things done to them. The more people included in the process of considering what it will mean for us to finally provide a sound, basic education to all, the better.

Our costs and our return on investment

As the conversation and debate unfolds about the WestEd report, it will be interesting to see if there is agreement across lines of difference around the findings and recommendations, especially the need for well-qualified teachers in every classroom and principals in every school.

The biggest sticking point may end up being the price tag. What are we willing to invest in education, North Carolina?

North Carolina Constitution, Article IX, Section 2 (1). General and uniform system; term. The General Assembly shall provide by taxation and otherwise for a general and uniform system of free public schools, which shall be maintained at least nine months in every year, and wherein equal opportunities shall be provided for all students.

North Carolina Constitution, Article IX, Section 2 (2). Local responsibility. The General Assembly may assign to the units of local government such responsibility for the financial support of the free public schools as it may deem appropriate.

I hope everyone will read the section of the WestEd report on finance and resource allocation, which starts on page 34. There are short-term suggestions and long-term suggestions. Here are some considerations as you consider the report’s $860 million per year recommendation in Exhibit 33 on additional funding beyond current state spending.

In North Carolina in 2018-19, 57.5% of the state’s general purpose revenue went to education, 22.4% to health and human services, 11.7% to justice and public safety, 3.8% to state reserves, debt service, and capital, 2.5% to agriculture, natural and economic resources, 2.1% to general government and information technology.

According to the Fiscal Research Division, the cumulative impact of enacted tax changes from 2013-18 based on the estimated fiscal impacts at the time of enactment are $0.3 billion saved for FY14, $0.9 billion for FY15, $1.3 billion for FY16, $1.9 billion for FY17, $2.4 billion in FY18, $3.1 billion in FY19, $3.7 billion in FY20, and $3.8 billion in FY21.

Under different political leadership additional tax revenue might even be an option.

The WestEd report notes, “resources committed to education decreased during the Great Recession.” So how does the next recession figure in? Jeff Chapman is the director of the state fiscal health initiative for Pew Charitable Trusts. In July when our paths crossed, I asked him to crystal ball the timing of the next recession. Whether it’s in six months (less likely) or 12 to 18 months (more likely) or even further in the future (a certainty), Chapman says the time is now to start talking about what to do when the next recession does hit.

North Carolina’s current rainy day fund has $1.25 billion in it. This Fiscal Survey of the States in spring 2019 by the National Association of State Budget Officers will help you assess the health of our fund relative to other states and to think about whether you’d be willing to spend any of it for investments in Leandro. A recent article by Chapman’s team suggests factors to be considered when it comes to rainy day funds, including spending increases in programs funded annually, like “debt service and state retirement system contributions, as well as federal-state safety net programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.”

Maryland has a Commission on Innovation and Excellence in Education chaired by Dr. Brit Kirwan. Maryland’s legislature convenes on Jan. 8, 2020, and it will take up the “Blueprint for Maryland’s Future.” Here is a recent return on investment analysis of the Kirwan Commission’s recommendations. Do you think we need an ROI analysis to assess the options?

“If our students were better prepared for college, careers, and the responsibilities of citizenship, North Carolina would reap tremendous benefits, wrote John Hood, president of the Pope Foundation back in 2016, noting broad agreement on that point. “If we improved the performance of our students to that of the highest-achieving state in our region, that would translate into an increase in gross domestic product of nearly $600 billion by 2095 — a 9 percent gain in real terms. If we improved the performance of our students to that of the highest-achieving state in the country, our GDP would rise by $2.1 trillion above the baseline, or 34 percent. And what if we focused on low-performing students rather than average scores? If North Carolina raised all of our students to at least a ‘basic’ level of competence in reading and math, the study found, our economy would be nearly $800 billion larger by 2095 than the baseline, an increase of 12 percent.”

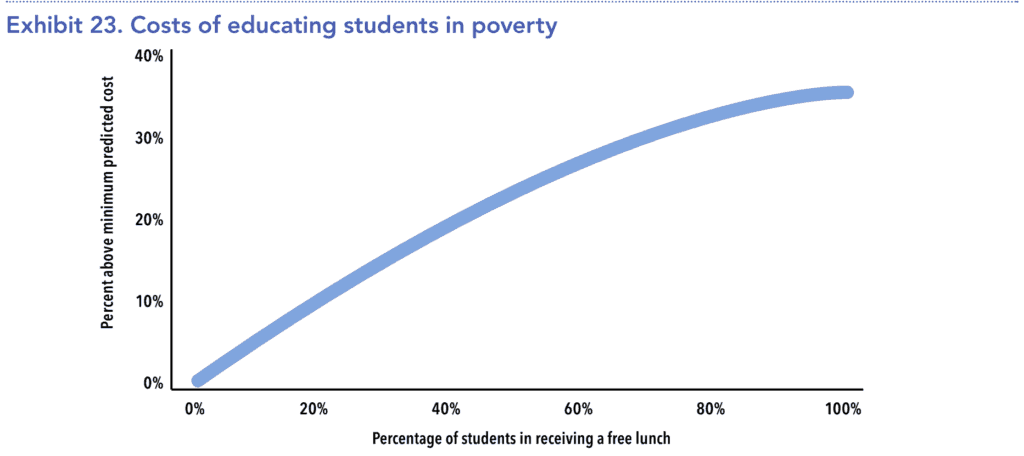

As she read through the WestEd report, Liz Bell, a reporter on the EdNC team, said based on her coverage of the Governor’s Commission on a Sound, Basic Education (she’ll be reporting on the similarities and differences in the Commission’s report and the WestEd report) and coverage of early childhood in communities across North Carolina, for her it all comes down to this graphic on page 36:

“The high per-pupil costs associated with serving high concentrations of economically disadvantaged students affects a substantial proportion of North Carolina schools; approximately 31% of schools in the state are serving student populations in which more than 90% of students are economically disadvantaged,” finds the WestEd report.

Serving student populations with greater needs and in higher concentrations is just one of several factors assessed and discussed in the WestEd report when it comes to the dollars and cents of providing a sound, basic education. Other cost drivers include regional variations, size of the district, local funding, local flexibility, and the state budget timeline.

Evidence-based practices AND innovation

“We need to build on established practices by giving teachers and school leaders the time and support to innovate,” says Rep. Graig Meyer, D-Orange. “Learning environments need to keep up with 21st century students and our evolving economy. We can’t do that if all we do is perpetuate an outdated system.”

The WestEd report finds, “In fact, the state now faces greater challenges than ever in meeting its constitutional requirement to provide every student with the opportunity to obtain a sound basic education. In large part, the increased challenges are driven by the major ongoing technological, social, and economic changes in our society.”

Singapore is the country many consider to be the best when it comes to education. The only natural resource in Singapore is people, and so they built their economy on educating the work force.

In Singapore, they believe schools should and will be designed — from the physical space, to the process of learning, and the role of the teacher — to encourage students to be the creators of knowledge. The creators of knowledge instead of the consumers of knowledge.

Our classrooms and our schools and our system of education need to be agile, nimble, iterative, future forward.

One of the great privileges of my job is to see innovation taking hold in districts across our state. Innovation that doesn’t wait for permission.

And I see the challenges of scaling the innovations.

Many of us got our first look at the WestEd report while we were attending the DRIVE summit, a historic gathering that promises to move us “towards a new landscape in recruiting, developing, supporting, and retaining educators of color.” As one of the only white women to attend the Million Man March in October 1995 — right around the time I was visiting schools for my research on Leandro — I don’t think I ever imagined seeing so many educators of color in one place in my state. Eric Davis, chair of the State Board of Education, took the hope of the DRIVE summit even further, declaring that North Carolina aspires to be “first in the nation in a diversified workforce in a high-achieving public school system.”

I’ve always loved it when North Carolina aspires to be the best, especially when it comes to education.

I remember when I first realized there was no federal constitutional right to education. It made our state’s constitutional right bigger to me, more important and more powerful — even though the court defined it to be sound and basic.

Turns out sound and basic is hard and complicated, and getting only harder and more complicated in the future, according to the report.

But the WestEd report also finds, “North Carolina’s public education system receives a substantially higher proportion of its funding from the state [62% v. 47% national average]. Consequently, North Carolina wields a particularly high level of influence in directing education funds toward where resources are most needed.”

That suggests we can do something.

Our constitution says it is the duty of the state to guard and maintain the right to education.

That suggests we must do something.

The question is how. The WestEd report suggests “an expert panel to assist the Court in monitoring state policies, plans, programs, and progress.” There is a lot of conversation that needs to be had about whether that’s the best way to move forward, what role the governor’s commission will play, and I sure would love a way other than a lawsuit for our elected leaders in the General Assembly to weigh in.

Even before that, people want to know how to submit corrections to the report and how to weigh in on the consent decree process.

Most days, I feel like the schoolmarm of North Carolina. Some of you love the new judge. Some of you miss the old judge. Some of you have long been worried about judicial overreach.

Some of you like WestEd but really wish they hadn’t partnered with LPI. Others of you love Linda Darling-Hammond and wish she had done the whole study. I can’t count how many of you have told me you don’t like that the report was done by “outsiders,” who some of you refer to as “not-from-heres.”

Some of you are worried about particular data points in the report.

Teach for America, where I serve on the board of directors for the eastern North Carolina region, weighed in with this statement:

Every child in North Carolina deserves an effective teacher. While we do have some questions about the age and accuracy of the teacher retention data in the report, we welcome the conversation that it is sparking. Today, over 64% of our alumni continue to work in education and are positively impacting thousands of students across the state as teachers, school leaders, and system leaders. As the recent DRIVE Summit highlighted, research shows that all students, and particularly students of color, are more successful when they have diverse and representative teachers leading their classrooms. We are proud that 49% of our teaching corps identify as people of color and 30% were the first in their families to go to college. Our diverse and talented corps members and alumni are expanding educational opportunities for students in classrooms across the state and proving what is possible in places like Edgecombe County. We are inspired by their collective impact and are excited to be part of the larger conversations and efforts across our state focused on what it will take to ensure that every student in North Carolina has the opportunity to attain an excellent education.

Some of you don’t like the politics of the case. Some of you wish the governor had waited on the commission until after the court had ruled. Some of you worry about separation of powers and don’t want the court to order the General Assembly to spend money. Some of you don’t like the consent decree process.

Some of you worry this report, like others before it, will sit on our shelves. Others hope we will remember it much like we remember “A Nation at Risk.”

A lot of you really wanted the WestEd report made public. Now it is. Read it. Talk about it. Call your legislator. Call the governor. Vote.

It’s our duty to guard and maintain the right too.

Weekly Insight Education