Despite facing some of the most pronounced economic challenges of anywhere in the Mid-Atlantic region, Danville, Virginia has a significant competitive advantage. The Danville Regional Foundation (“DRF”), set up in 2005 at the sale of the Danville Regional Medical Center, is a driving force in Danville and the surrounding region. The Foundation takes an active role in supporting economic development and using philanthropy to fill-in gaps left by the public and private sectors. DRF is distinctive in the way that its leadership uncovers the cutting edge around community and economic development, both through grants to the community and through thought leadership across the country.

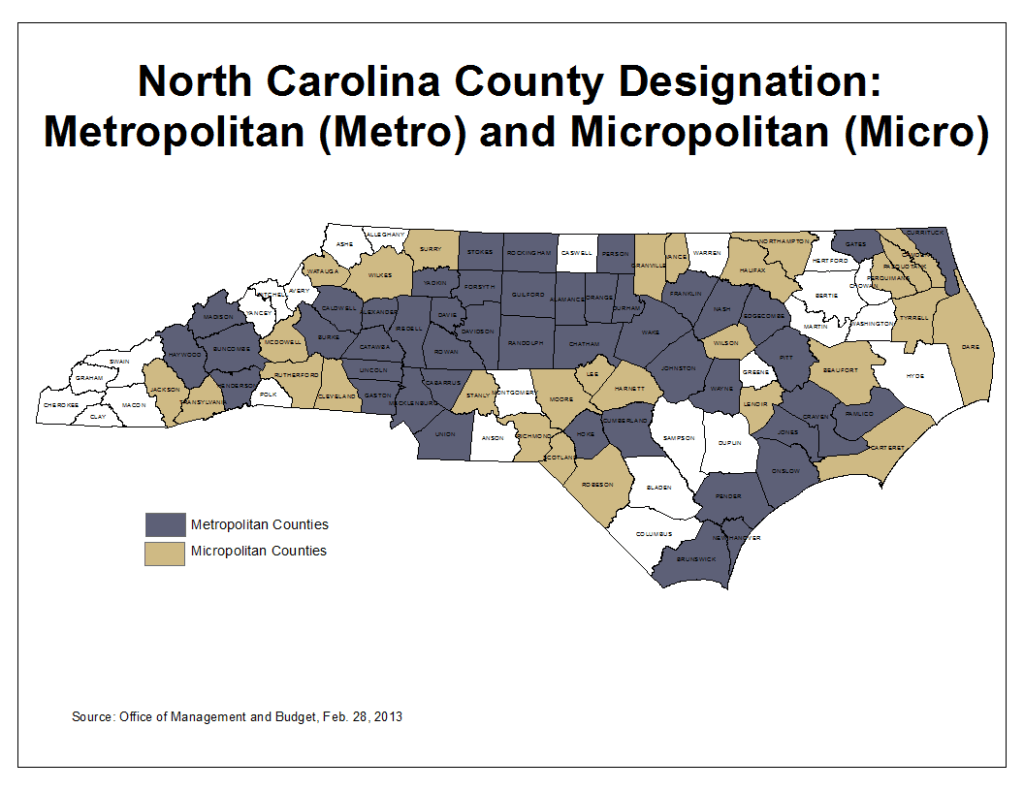

DRF recently hosted the “Home of Future Thinking” conference geared around small cities that are outside the orbit of larger metropolitan areas. The U.S. Census Bureau calls these micropolitans, and there are 551 of them in the United States.

DRF, whose micropolitan region includes Caswell County, North Carolina, convened the event focusing on two types of participants. First, they invited representatives from nine different micropolitans across the U.S. The second group was a broad cohort of policy types from a variety of places and areas of expertise. The goal was to give the government representatives a chance to learn from each other and connect with the policy folks with hope of sharing information and solutions about common issues.

Danville region individuals were not the only representatives from North Carolina; participants came from Hickory and Wilson as well. Added to the mix were delegations from Appleton, Wisconsin; Cedar Rapids, Iowa; Macon, Georgia; Michigan City, Indiana; Portsmouth, Ohio (representing the southern Ohio region); and Tupelo, Mississippi.

The conference was designed to stimulate discussion by focusing on guided conversations instead of speeches, with lots of room for questions and answers. It concluded with a full half-day of focused, group work on different issues. There was a lot to process, but here are five ideas/takeaways:

1. Differences are as pronounced as similarities

At the end of the first day, representatives from the different communities talked about what was challenging and what was going well for them. I expected to hear a lot of common themes but was surprised by how different the areas are in place and time.

For example, I expected to hear that declining population was a theme. In reality, it was only an issue for half of the participants. Most communities were not growing fast, but at least half were growing. Some of those that were not growing were not necessarily seeking growth.

In addition, I expected to hear “jobs” was the chief challenge. It was a common refrain but in different ways. In several communities, including Wilson, NC, the challenge was less the number of jobs than the disconnect between the jobs and the employees in the area. On the other hand, in natural resource rich southern Ohio, the concern was not having enough suitable sites available for those interested in taking advantage of the natural resources. In Appleton and Cedar Rapids, they have high levels of employment but are concerned what will happen in five to 10 years when much of their skilled workforce retires.

2. Millennials ≠ lattes & sriracha

At several points in the conference, there was a sense that economic development language is bogged down by the term, “millennial.” There was a sense that the idea has become burdened with side meanings, particularly around elitism and populism.

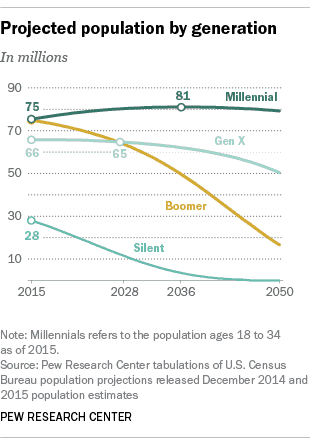

Keynote presenter Alan Mallach of the Center for Community Progress noted that in many media contexts “millennial” is now a descriptor for the 30 to 40 percent of 18 to 40 year olds that have a higher education, particularly when it is used in relation to social and cultural data points. As Mallach quipped, the true generation is much broader than the “sriracha and latte” culture and, as a whole, includes many people whose goals and preferences do not resemble the popular portrayal.

Personally, I have witnessed 30-year olds cringe when someone from an older generation identifies them as millennials. They do not know what is coming, but they brace for some assertion about them that is based on narrow cultural factors.

In reality, the last of the millennial generation cohort will be voting in the next couple of years. Millennials are now a plurality of American adults. While the technology and culture of their era has evolved quickly, as a generation they are unlikely to be drastically different than other generations. While demographers and sociologists should track and call them what they will, it may be time for others to simply call them fellow adults.

(Postscript: this piece by Elizabeth King at CityLab interviews author Malcolm Harris and makes a similar point.)

3. Innovation versus community

Bill Bishop, another of the keynote speakers and author of the Big Sort, observed a tension between cities that are good at building community and those that are good at building innovation. Bishop suggested that, by nature, communities are rarely good at both because what drives people to create and invent things is a focus on the individual, whereas what drives strong communities is a commitment to self-sacrifice for the benefit of the whole.

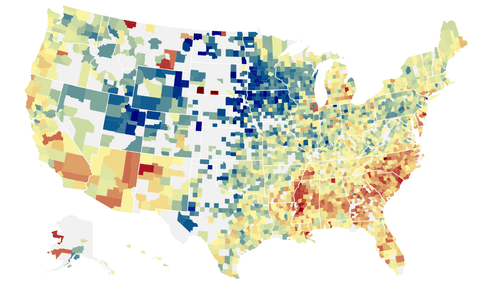

To illustrate his point, he narrowed the definition of community-building as the ability to educate children from poverty. He then applied the research of economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren (here and here), who have examined decades of income tax data. The statistic that Bishop used looked at counties’ ability to positively affect poor children’s income. Put another way: what percentage of poor children in a county improve their standing compared to other counties? In metropolitan counties, Bishop recalled that 25 percent of children improved their standing. The number rose to two-thirds in micropolitan counties and three-fourths in rural counties.

(In 2015, the New York Times “Upshot Blog” did an in-depth overview of the data set Bishop referenced. It is complete with summary articles and interactive maps showing where specific areas fall in relation to national averages. In North Carolina, the trends appear even more pronounced, with the most populous metro areas being among the country’s worst for upward income mobility and the micropolitan and rural counties being clearly stronger.)

It is a provocative way to think about education and community building.

4. “The cat rarely brands itself”

Some of the most informative sessions of the conference were ones involving Andy Levine, CEO of Development Counsellors International (DCI), a place-marketing company. Like any good marketing expert, Levine was full of digestible frames and practical advice. One of the best the ideas was that smaller communities need to focus more on developing third-party endorsers to tout their strengths rather than expending resources on self-promotion. Successful companies and political candidates know this, but too many communities are slow to realize it. Specifically, Levine proposed relying three endorsers: (1) corporate leaders, (2) people who have moved to an area and are happy, and (3) the media to tell the story.

5. Bring back your sons and daughters

Three of the nine community leaders who represented their micropolitan community at the conference were 30-somethings who had spent time away from their community and returned home. That observation, as well as several of the discussions with community leaders, reinforced some research that I did 10 years ago: in many communities, the solution lies with these absent sons and daughters who left home in their twenties. Every micropolitan community has leaders who can tell stories about their daughters in New York or their sons in Charlotte. In some cases these expatriates are considering a return home, but in all cases we can learn about what factors keep them elsewhere and what communities can do to improve the odds of them returning.

Stay tuned for some links to conference material as well as to some video clips of the more formal sessions.

Weekly Insight Demographics Economic Development Rural