Earlier in this decade, with North Carolina’s economy broken but on the brink of resurgence and its population swelling, fewer young people wanted to be classroom teachers. Fewer mid-career adults thought it prudent to switch jobs and become teachers. Fewer educators stuck it out — for less money than their peers in most other states — in a career with heavy burdens and even greater stakes.

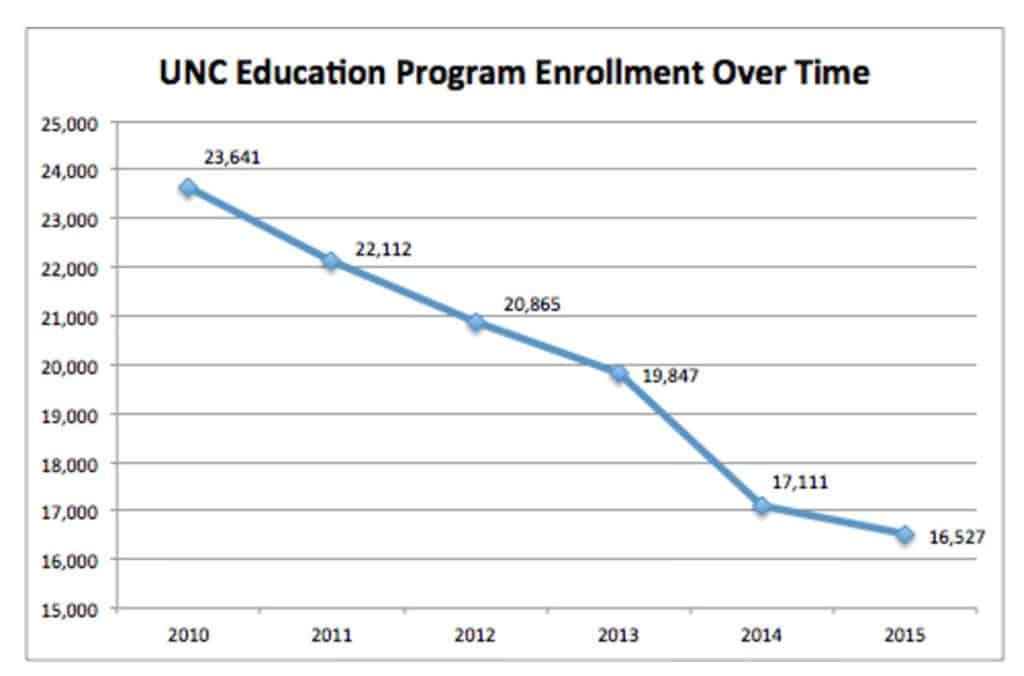

By 2015, enrollment in the state’s public university teacher training programs was down 30 percent from just five years prior. At the same time, teacher attrition rates climbed into double digits. North Carolina school districts struggled to find enough qualified teachers to fill vacancies and keep up with enrollment growth.

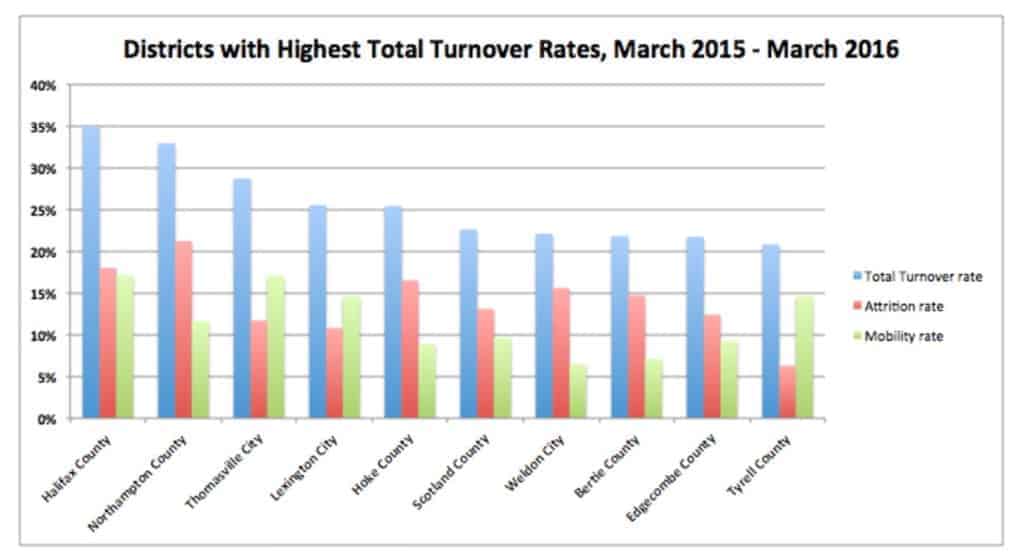

Those shortages were not uniform. Rural communities worked to keep their heads above water as turnover created more vacancies than districts could fill. Larger, urban districts leaned on quality of life amenities to lure educators to city life, but then struggled to fill jobs at low-performing campuses.

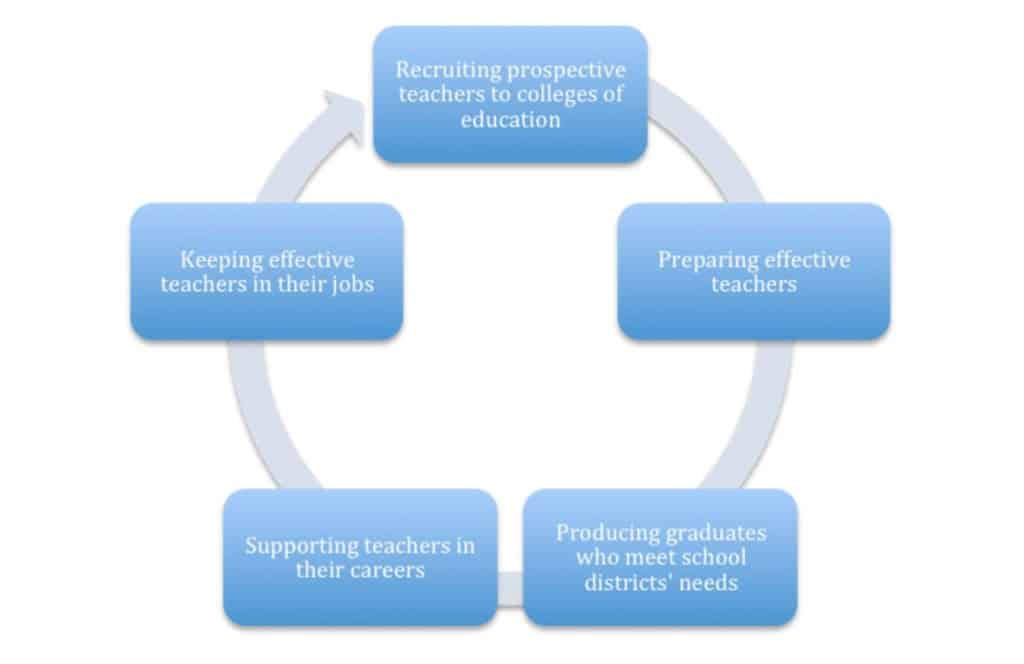

The teacher pipeline is less of an arrow and more of a loop, a cycle whose health depends on a variety of factors, says Alisa Chapman, a fellow at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Global Research Institute. Before starting at Carolina this past spring, Chapman spent nearly two decades closely studying public education, and the teacher pipeline in particular, for the University of North Carolina system.

Chapman often breaks the challenge into five big buckets: Successfully recruiting enough prospective teachers to colleges of education; preparing them to be effective; producing graduates who meet school districts’ needs; supporting teachers, particularly in the early stages of their careers; and keeping effective educators in their jobs.

“We have had — historically in North Carolina, and I believe it still to be true — as much of an issue with supply and demand as we do with distribution of teachers, geographically, across our state,” says Chapman.

The state’s teacher shortage is the result of a confluence of factors beyond education — politics, economics, and a widening urban-rural divide — that together create a cycle worthy of intervention by policymakers, educators, individuals, and systems in different regions throughout North Carolina.

“The challenges in Wake County are very different than the challenges in Watauga County,” says Terry Stoops who studies education policy at the John Locke Foundation in Raleigh. “We may have to be a little more sensitive to solutions that are focused on regional conditions rather than on some big, wide solution. I strongly oppose those who think there’s a one-size-fits-all answer.”

![]()

The problems, this time around, started to show up in 2010.

That fall, 23,641 people enrolled in undergraduate and graduate-level education programs at schools in the University of North Carolina system, according to UNC system data. Bachelor’s degree student enrollment outpaced master’s enrollment by roughly a two-to-one margin.

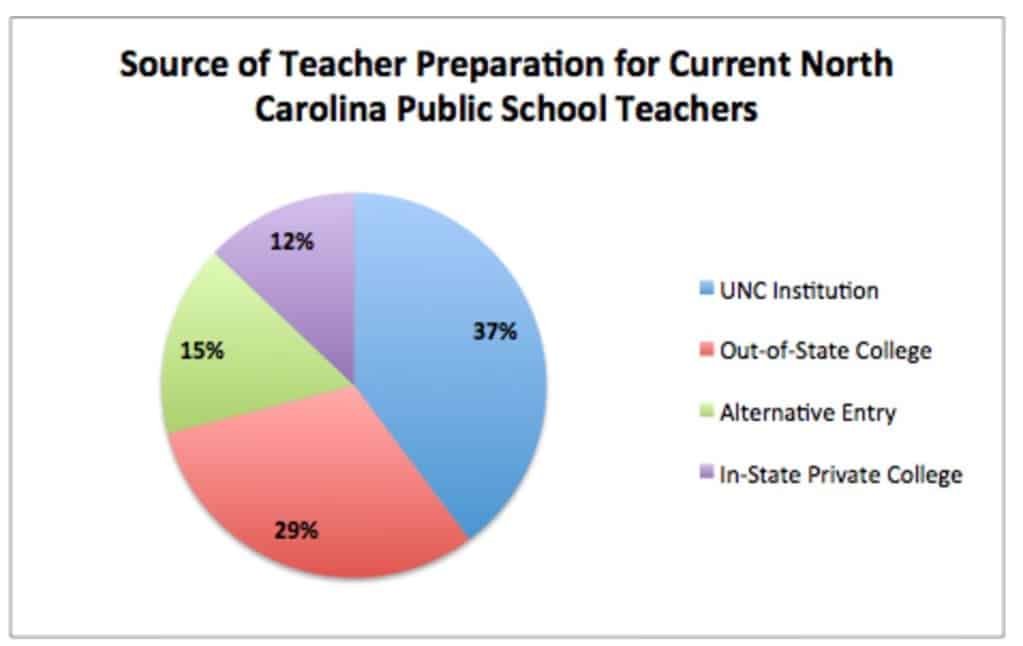

But applications for the following year were down, and projections for future classes looked bleak. By 2015, enrollment had dipped to 16,527 — a 30 percent drop in five years. “The University of North Carolina is the single largest supply source of teachers for our public schools so the work we do in terms of producing educators for our workforce and the quality of that preparation is critically important to our state,” Chapman says.

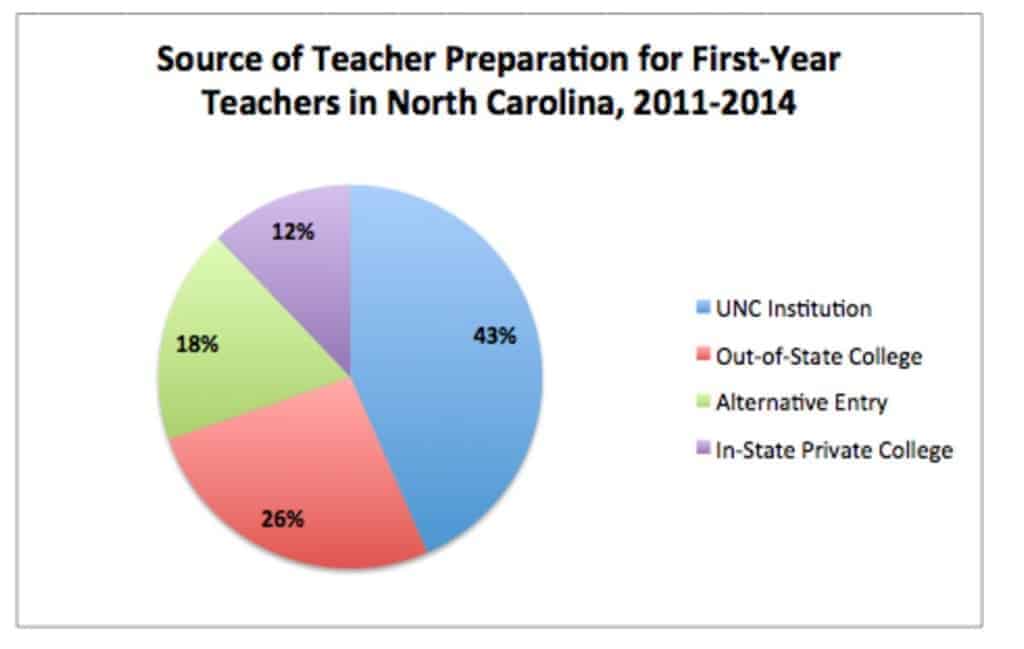

About 37 percent of all current North Carolina public school teachers came out of a degree program at a UNC system institution. Another 29 percent came from out-of-state colleges, 15 percent switched careers and became alternative entry teachers, and about 12 percent graduated from in-state private schools.

Roughly 44 percent of first year teachers in North Carolina graduated from UNC system schools, up a bit from the chart below.

So when those colleges experience a dramatic drop in enrollments — such as the 34 percent plunge in enrollment at Appalachian State University from 2010 to 2015 — the effect on school districts, who depend on the UNC system to fill teaching vacancies, is real. Layer on top of that an increase in teachers who leave the state or the profession altogether, currently about 9 percent of teachers annually, and you have the outline of North Carolina’s supply and demand challenge.

Before 2016, the turnover rate accounted for teachers shifting between schools, districts, and positions. Now, the attrition rate tracks only teachers who are no longer employed by North Carolina public schools. While the state has changed the way it calculates attrition, or the loss of teachers, and mobility, or transfers from one district to another, experts generally agree that North Carolina lost public school teachers at a greater rate this decade.

“We know that churn of teacher turnover is not healthy,” Chapman says. “It brings instability to our schools.”

![]()

This is not the first teacher shortage North Carolina has had, nor is ours the only state in America struggling with such a challenge.

“It’s never one issue,” Chapman says. “I do think there are links to the economy, there are links to structures of leadership at all levels, but it’s never just one issue. These are complex problems.”

Indeed, other states, particularly in the South, have struggled with similar challenges with teacher supply. Stoops says Georgia has been effective in cobbling together remedies to address its teacher shortage — though its policy solutions might not be a helpful analogue.

“I always caution folks not to look at models that exist in other states,” he says. “We really need to think about what would work best here in North Carolina. We have a different dynamic with our community, with our urban and suburban cores, our rural areas.”

A report released last September by the Learning Policy Institute highlighted a 35 percent drop in education program enrollment nationally during the same period as North Carolina’s most recent shortage.

The study’s authors estimate American schools need to hire about 260,000 teachers a year — largely to replace those who have quit — but only have a supply of 196,000, a shortage of 64,000 teachers. But the demand for teachers is growing, thanks to an increase of school-age children, the reinstatement of pre-recession programs and class sizes, and an 8 percent attrition rate. The LPI study suggests the national teacher shortage could jump to 112,000 by 2018. “The teaching workforce continues to be a leaky bucket,” the authors say.

They noted that “high-achieving jurisdictions” such as Finland and Singapore, often cited as countries with excellent teachers, have an attrition rate of between 3 and 4 percent. “Changing attrition,” the report says, “would reduce the projected shortages more than any other single factor.”

“They accomplish this virtuous cycle of selecting teachers well, preparing them well, inducting them well, supporting them well,” says Leslie Winner, a retired state legislator and former head of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, speaking of Finland and Singapore. “So they have very little turnover and that feeds their ability to selectively invest in preparing them and invest in supporting them.”

She says the state’s inability to support existing teachers — through pay but also through professional development and opportunities for career growth — fuels attrition rates that exacerbate the scarcity at the beginning of the cycle. The state is at such a deficit that it can’t afford to be selective.

“We don’t retain them well, so we need a lot of new teachers every year compared to them. Therefore, we’re not selective in selecting them, we can’t invest in preparing them.”

A calling

Carlen Burch considered education as a possible career as she headed off to college, but she was not certain.

“Teachers are lifelong learners,” she says, “and I could see the passion in all of the teachers I had in school.”

Burch, who grew up in Chapel Hill, enrolled at Coastal Carolina University in South Carolina but the program wasn’t a good fit, so she transferred to UNC Wilmington. The teacher preparation curriculum resonated with her, and she began to be drawn to a career teaching students whose native language isn’t English.

This month, she starts her final semester at Wilmington. She’ll finish her student teaching in a local elementary school, and then be ready to enter the profession full-time. “I’m nervous but I do feel ready,” she says.

That has not always been the case.

Throughout her time in college, Burch says, family, friends, and strangers have attempted to dissuade her from becoming a teacher, citing a host of reasons — pay, prestige, working conditions. “I definitely did doubt myself,” she says. “But I realized that salary isn’t the most important thing, and I truly think my passion speaks louder than their opinions.”

“We find that when we go into the schools and talk to young people about teaching, we still find a lot of young people still want to be teachers,” UNC Charlotte College of Education Dean Ellen McIntyre told EdNC last year. “It’s really heartening.”

“But,” notes McIntyre, “some of them will say their families, their parents, discourage them from going into teaching. Public perception of teaching is often more negative than actually what teaching is really like.”

Anecdotally, the refrain from many prospective and beginning teachers is similar:

They feel a calling to the profession that supersedes other motivations.

“For as long as I can remember,” says Keaton Huffman, a North Carolina middle school teacher, “my siblings and I would play school.”

“I grew up wanting to be a teacher,” says Abby Rich, an elementary education major. “I would teach to my pretend class on a small dry erase easel in my playroom.”

“I had always wanted to change lives, to help kids,” says Nathan McDaniel, who wants to be a middle school teacher.

All three — Huffman, Rich, and McDaniel — enrolled at Appalachian State University with the help of scholarships provided through a $1.76 million grant from the State Employees’ Credit Union. They relayed their individual stories in an effort to thank local SECU advisory boards for supporting the scholarship grants.

Understanding their desire, developing it, and eliciting it from others appears critical to solving at least a piece North Carolina’s teacher shortage. “I can promise you I didn’t choose teacher education for the financial compensation or even because of my love for reading and writing,” says Huffman, the middle school teacher. “I sincerely chose education for the students.”

![]()

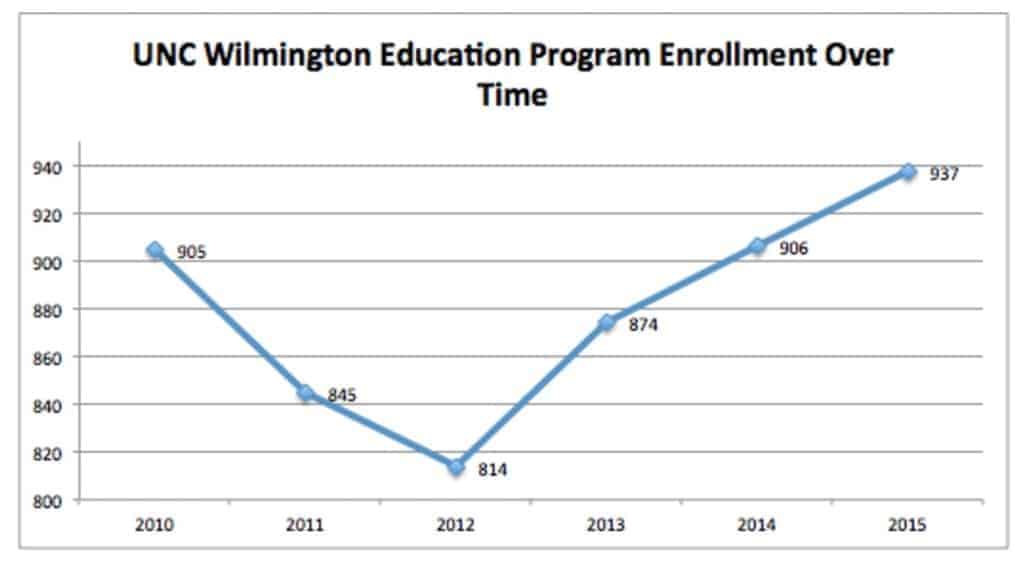

Although enrollment in education degree programs at North Carolina’s public universities was down roughly 30 percent over the past five years, the worst of the enrollment slide appears to be over.

The UNC System saw a 16 percent increase in those seeking an education degree last year, reports WUNC.

Chapman says it is too early to determine exactly the factors in the enrollment trends. But there are some lessons to learn from UNC Wilmington, which bucked the trend. Its enrollment drop was not as precipitous, and it began to see a rise in the number of prospective teachers signing up for classes sooner.

“We take recruitment seriously,” says Van Dempsey, dean of the UNC Wilmington College of Education. “We work hard at it. We try to build our knowledge base about recruitment and our capacity to do it.”

Dempsey is a native North Carolinian — he grew up in Halifax County and early in his career taught high school social studies in Fayetteville and Pittsboro — and says staffing schools is far more complicated today than it was 30 years ago.

UNC Wilmington battled its education enrollment decline with a mix of remedies, everything from a marketing campaign that highlighted positive stories about educators to financial grants for early childhood education majors. The college boosted its distance education and scholarship packages, too.

Even still, the pool of young people who have always wanted to be teachers simply is not big enough to keep up with demand for public school educators in this state, creating a sense of desperation in some communities. Principals joke about needing “warm bodies” in their classrooms when classes start this month.

“What we want is to have some degree of selectivity,” Dempsey says. “Not everyone is destined to be a teacher and we have to be willing to say that confidently: Teaching is a profession that does not suit everyone.”

That is why Dempsey is still concerned about the teacher pipeline, even though UNC Wilmington’s enrollment numbers are climbing.

“We don’t solve solve this problem and then get to take a break for two or three years,” he says. “It’s steady work.”

![]()

One of the debates in North Carolina — because it’s been difficult to attract traditional college students to teaching in the last decade — is how best to bring non-traditional educators to the classroom.

“As a state we need to consider the implementation of high quality alternative pathways,” says Stoops at the John Locke Foundation. He says the state can do more “to make sure that transition is as smooth as possible and is respectful of the fact that these individuals have knowledge that can be leveraged.”

Stoops says the state needs to figure out how to lure potential educators in specific fields. “I don’t know that we have done enough to incentivize students in math, science and special education to go into careers in education and further incentivize them to teach in a North Carolina public school, particularly those high-need or low-income communities.”

The General Assembly this session passed Senate Bill 599: Excellent Educators for Every Classroom, that allows external groups —including private, for-profit organizations — to operate teacher preparation programs in North Carolina. The measure also creates a Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission which would evaluate those programs and make recommendations to the State Board of Education.

Dempsey says although North Carolina is in need of teachers, the state ought to be careful about how it goes about finding and training them.

“For some amount of time, children are going to have teachers that are going to come through routes that don’t look traditional, they don’t look like the routes that existed when I became a teacher,” he says. “But the remedy is not to remove rigor in other places, open the flood gates and let anybody in. The challenge is to shore up the rigor.”

Like Stoops, he suggests the state invest in scholarships or forgivable loans to help underwrite the college education for prospective teachers who commit to North Carolina public schools.

North Carolina’s nationally-known Teaching Fellows program subsidized the cost of prospective teachers’ college education, with a requirement of service in the state’s public schools after graduation. Critics said the program was not as effective as it should have been, and the legislature dismantled it beginning in 2011. In the years since, lawmakers have introduced similar scholarship programs, and this session they passed a new teaching fellows program focused on STEM and special education. The legislature has also funneled money to Teach for America, which now provides about 2 percent of the state’s new teachers each year, in a select number of districts.

“The reward system, the salary, the incentives that we put into the teaching profession,” Dempsey says, “are not sufficient to be able to draw the sheer number of people we need in the profession.”

Much has been made about North Carolina’s low teacher salary rankings over the past decade, and the General Assembly’s attempts to boost those numbers, especially for beginning teachers.

“We have a long way to go, I think, in terms of pay and the other kinds of support that’s necessary to retain teachers,” says Winner, the former head of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation and a retired state legislator. “But it’s not just all money. It’s a combination of money, social life and environment, and some sense of the difficulty versus reward of teaching in particular places.”

Stoops agrees, although he is quick to note the balance state legislators must achieve between teacher salaries and other taxpayer-funded priorities. “Teacher compensation matters, but taxes, jobs, and infrastructure matter, too,” he says. “It’s one part of the equation, but we have to remember teachers are not just teaching. They’re living. And they’re often living with a significant other…a family.”

This year, the General Assembly passed a biennial budget that included an average teacher pay raise of 9.6 percent, though the actual increase an educator will see varies dramatically. Teachers with 17 to 24 years of experience will get the biggest raise. Beginning teachers, who were the focus of previous legislative salary bumps, did not earn more under the state budget.

To underscore that point, Carlen Burch says she is not sure where she will end up teaching when she graduates from UNC Wilmington at the end of this semester. It will depend on where she gets a job offer; the characteristics of the community, school district, and campus; the salary; and some sense of whether she can make a difference for the ESL students she hopes to serve.

“I’m not ruling North Carolina out, but who knows if that’s where I’ll be,” she says.

Raising the bar

They arrive, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed or hungover and in sweatpants, and unpack their bags. Laptops out, notebooks open. They are ambitious and uncertain, scared and convicted. In many ways, they are still children themselves.

A year from now, some will be teaching public school students across North Carolina.

Although the University of North Carolina system is the state’s leading producer of beginning teachers — 44 percent of all new teachers, according to the most recent data — public universities can’t sustain the demand of a growing school-age population and leaky teacher workforce pipeline.

“In many other states, particularly those states that North Carolina draws teachers from, they have a declining K-12 student population,” says Chapman who studies the teacher workforce at UNC-Chapel Hill. “That’s not the case for us.” In other words, the decline in education college enrollments in other states may be, in part, a natural correction for a shrinking population.

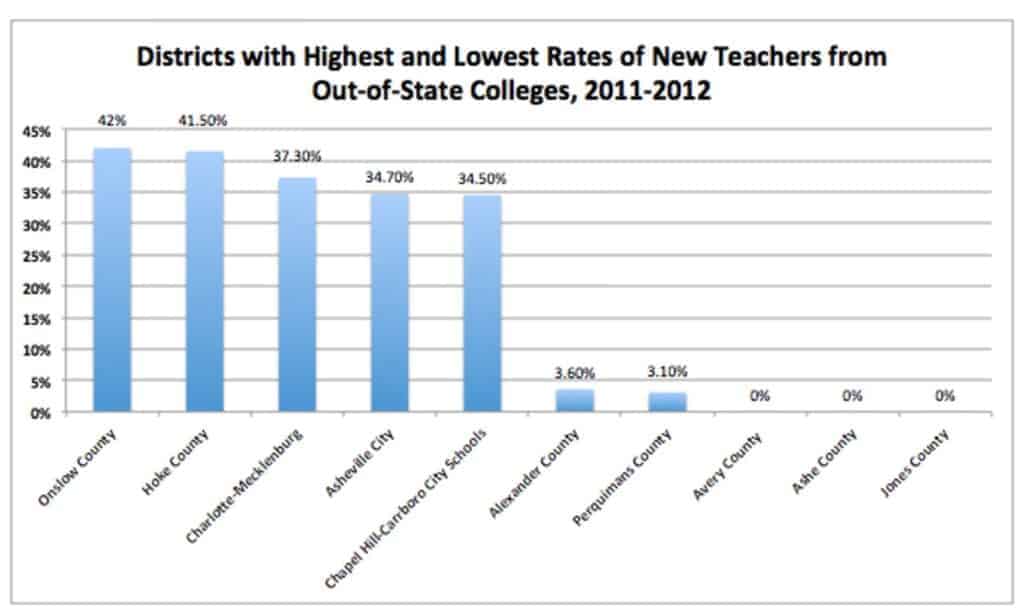

A glut of new teachers in other states, together with attractive amenities and plentiful job vacancies in North Carolina, inevitably draws out-of-state educators here.

“The very best and brightest teachers in those states — this is our theory — get jobs, and the other teachers look for employment elsewhere,” Chapman says. “Some of those individuals wind up in North Carolina. Teachers educated in other states make up 25 percent of North Carolina’s beginning teachers, and 29 percent of the overall teaching workforce here.

Teachers prepared out-of-state are more heavily concentrated in North Carolina elementary schools, Chapman says, and that’s where their performance is most challenged. “We need to lessen our state’s dependency on those supply sources that don’t meet the expectations that we have for our public schools.

“In a sense, North Carolina is a farm team for teachers prepared out-of-state.”

![]()

When first-year students arrive at UNC Charlotte’s education school, they do something teacher educators would not have imagined a decade ago — they go into the classroom.

“Gone are the days of teacher preparation programs having student teaching as their field experience at the end of the program,” Ellen McIntyre, the school’s dean, told EdNC last year. Indeed, the UNC system is taking a hard look at what is known as “clinical practice,” or the hands-on experience prospective teachers get through student teaching, internships, and job shadowing. “That’s a big change for a lot of institutions,” McIntyre said. She said the school is especially focused on more effective coaching for student teachers so they can get more out of their clinical practices.

Such a partnership is emerging between UNC Charlotte and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. In August, 55 CMS freshmen enrolled in the five-year program aimed at prospective teachers. The idea is similar to existing early colleges across the state for other professions, typically those in STEM fields; a partnership between UNC Charlotte and CMS already exists for prospective engineers.

The Charlotte Teacher Cadet Early College is the first of its kind in North Carolina — but it likely won’t be the only one. John Farrelly, who at the time was Edgecombe County Schools superintendent, says his eyes widened when his counterpart in Charlotte, Ann Clark, filled him in on the early college plan. “She told me what she was doing and I said, ‘Ann, I’m gonna run back to Tarboro and put the wheels in motion on this.’”

Several weeks later, Edgecombe County staff had a plan to launch a similar program there.

![]()

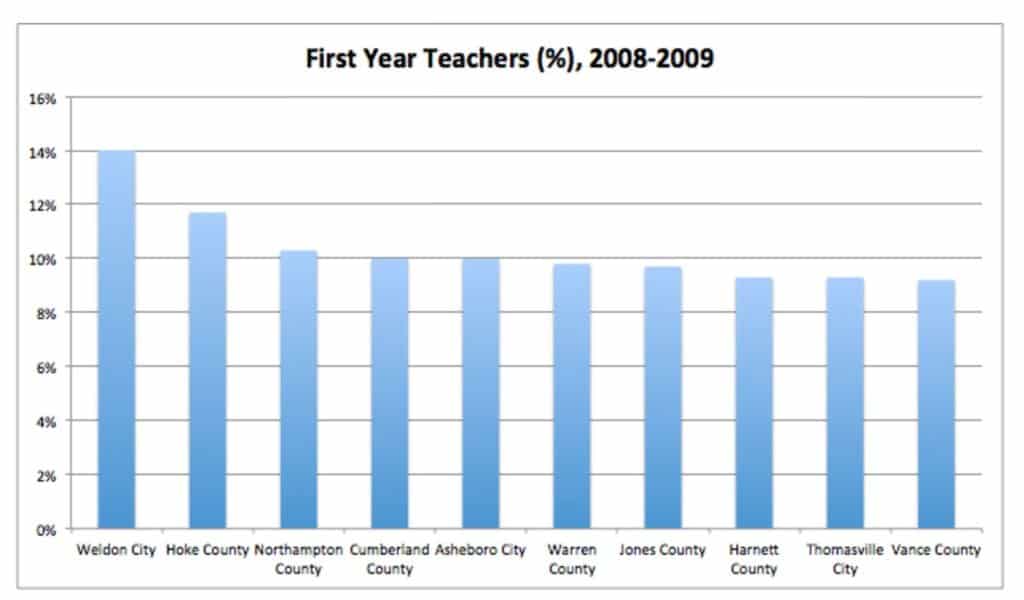

Training teachers to be effective from their first day in the classroom is critical because so many current educators are beginning teachers.

In 1987, American teachers stayed on the job about 15 years. Today, it is one year nationally and about 1.5 years in North Carolina. About 7 percent of all teachers in North Carolina are in their first year of teaching, according to UNC system data, higher than any other year of experience. Roughly a quarter are in their first five years in the profession.

“We have a greening workforce in our state,” Chapman says, and those trends are exacerbated in rural school districts and those that serve poor and minority students. “Our hard to staff schools are rural. Not always, but often.”

“First year teachers are disproportionately reflected in our state’s lowest performing schools.”

Critics say the North Carolina’s public universities have not done a good job preparing college students to become educators, and that failure has contributed to the state’s teacher pipeline squeeze.

“Our schools of education at North Carolina colleges need to do a better job of preparing teachers for the classroom,” said Senate Majority Leader Phil Berger in a 2015 speech to Best NC, a business coalition that advocates for education reform. “The truth is, we either need to fix our schools of education in North Carolina or scrap them in favor of new and different approaches to teacher preparation. It doesn’t make sense to do both.”

UNC System President Margaret Spellings does not go quite that far — but she does support the addition of privately-run teacher preparation programs in North Carolina. “Given our demand and our needs, we need to find new and better ways,” she said at a gathering of education and business leaders earlier this month. “Other providers are certainly welcome and needed.”

Spellings said she is excited about the possibility of new teacher preparation programs entering the state and that the university system would be a “a strong participant, as many others will be, in the creation of these new pathways to teaching.”

Evaluations of North Carolina’s teacher prep programs indicate mixed results.

“There is room for improvement in our schools of education,” says Stoops at the John Locke Foundation. “But I don’t know that I would lean on the criticism that they are the reason why we’re having such a difficult time staffing schools in certain areas.” Stoops says there are inconsistencies across campuses. And he says that, in the aggregate, colleges of education might not be producing teachers in the fields North Carolina public schools need the most.

In late 2016, the National Council on Teacher Quality released a report evaluating 875 undergraduate elementary teacher preparation programs, including 26 in North Carolina. Among those universities, the top three performers were private schools: Elon University, High Point University, and Meredith College. All three scored at or above the 90th percentile. The next three programs were those at public universities. UNC-Chapel Hill’s program scored a 66, UNC-Charlotte received a 60, and Appalachian State earned a 52.

The state institutions did receive high marks in some areas — UNC-Charlotte, for example, received an A+ ranking for its reading instruction preparation—but did not score well in math instruction or student teaching.

Nationally, only 5 percent of teacher preparation programs reviewed by NCTQ incorporated “elements of a quality program” into their student teaching experiences. “There is no data point out there that shows teacher prep functioning as well as it should be,” says Kate Walsh, the council’s president.

UNC educators admit their programs can do better.

“I do think we need to own some of that criticism,” Chapman says. “There is absolutely room for improvement in UNC educator preparation programs.”

She says the UNC system has put in place a number of evaluation tools, including an “educator quality dashboard” that tracks teacher performance. “This lets us know with far greater precision where our teacher preparation programs need to hone in and work on improving their programs,” she says. “We want to address program improvement and we want to do it with valid, reliable research and data.”

College deans agree.

“What we do is critically important and right now I think as a field we aren’t doing well enough,” McIntyre, the UNC Charlotte education dean, told EdNC. But she said not all of the criticism leveled at colleges of education is warranted. “We’ve heard it said by people maybe who, we think, have never set foot in one or talked to any of us… People really don’t know what it is we do and just how hard it is to prepare teachers.”

But even public school superintendents say there’s more that the higher education system can do to prepare teachers for the classroom.

“We need to do a better job of sharing what we’re seeing in graduates and what we’re not,” says Farrelly, the eastern North Carolina superintendent. “We see a lot of teachers come out with the technology skills necessary to inspire and motivate children with. But the ability to raise the bar significantly with literacy…that is kind of like the pink elephant in the room.”

No stone unturned

Jessica, an experienced middle school educator in Charlotte, loved to teach. She stayed late, applied for a “teacher leader” position, traveled to out-of-state professional development conferences. She hung her students’ artwork on her fridge at home. But, in her early 30s, she realized she couldn’t afford to rent an apartment in Charlotte’s urban core by herself.

She started to update her resume.

Teachers leave North Carolina classrooms for all sorts of reasons.

Some, like Jessica, get fed up with the pay or the working conditions or the bureaucracy and quit. Others get promoted. A few move to charter or private schools. They have children of their own. They retire.

The state reported a 9 percent attrition rate in the 2015-16 school year — but the important point is that teachers are leaving. Much of the teacher pipeline conversation in North Carolina centers on the flow of prospective teachers into the profession: How do we recruit them? How to we train them?

The state must also stem the tide of teachers leaving the state or the profession altogether. “Just addressing the overall supply side is not going to be an adequate solution for our state,” says Chapman. “We have to look at both ends of the spectrum.”

Chapman says the UNC system has done some “back of the envelope calculations” that illustrate this point. If North Carolina retained half-a-percent of all new teachers annually for the next five years, Chapman says, it would need about 2,300 fewer beginning teachers. “The more that we can do to support beginning teachers and retain them,” Chapman says, “the much greater benefit there is for our public schools.”

![]()

One way to keep people in any profession is to compensate them well. The General Assembly has boosted salaries, especially for beginning teachers, in recent sessions. An average North Carolina teacher will receive a 3.3 percent raise in the first year of the biennial budget lawmakers passed during this year’s session, although raises are spread unevenly — beginning teachers receive no pay bump, while veteran teachers who have not had substantial raises for years see a larger increase. But the state pay scale is only part of the equation.

The local supplement — how much counties tack on to the base salary provided by the state — makes a difference in how much teachers actually take home. Because of their bigger tax base, urban areas can pump extra money into teacher salaries to make their positions more attractive to prospective teachers.

“In Edgecombe County, a teacher can get in the car and drive an hour and five minutes to Raleigh and increase their supplement from 7 to 20 percent,” says John Farrelly, who served as Edgecombe County superintendent until earlier this year when he took the same job in Dare County. “That’s probably the difference between $5,000 and $15,000. Legitimately, that’s the difference between whether I’ve got to go out and get a second job or not.”

He suggests lawmakers consider the idea of a statewide supplement that would help rural and exurban school districts be more competitive with urban and suburban ones. In the meantime, Edgecombe County commissioners have voted to increase the local supplement from 4 percent to 7 percent, and could go up to 11 percent within the next biennium. “The reality is folks have gotta put food on the table,” Farrelly says.

Edgecombe County historically has had one of the highest teacher turnover rates in the state — somewhere in the 25 percent range, Farrelly says, when he started as superintendent five years ago. The rate is falling and could dip below 20 percent this year. Farrelly credits a mixed bag of programs, partnerships, and outside-the-box thinking that converge to aggressively fight teacher attrition.

A similar tactic, he says, is necessary in most rural counties. “There’s not one silver bullet out there,” he says. “It has to be a no stone unturned approach.”

Most experts who study the teacher workforce agree that long-term career options — opportunities for growth and development, instead of feeling stuck in the same classroom — are critical to retaining the best educators. “Teachers respond and grow when they get consistent feedback that is specific and tailored to their needs,” Farrelly says.

The UNC system has started a support program for beginning teachers, the North Carolina Beginning Teacher Network, which is designed to do just that. “Our early outcomes are very promising,” Chapman says. “Teachers served by this program are retained at higher rates and we’re seeing some positive effects on student achievement, particularly in math and English language arts.”

But the program’s scope is narrow, and its budget is small, leaving plenty of teachers across the state without the support and professional development they crave. Less effective educators do not improve, and good ones do not flourish. Teachers begin to feel stuck.

Edgecombe County joined in a State Board of Education-led teacher compensation pilot program, one of only six districts in the state to be included; partnered with N.C. State University to provide a year-long training and internship program for prospective administrators; and launched Public Impact’s Opportunity Culture program, in which teachers are paid substantially more to take on additional leadership and mentoring responsibilities.

The district will start implementing Opportunity Culture in three of its schools, then expand to the remaining 11. The hope is that the cocktail of programs, coupled with a low cost of living, will make Edgecombe County not just tolerable but desirable for teachers.

![]()

Edgecombe County’s situation is emblematic of North Carolina’s widening urban-rural divide, and of the fallacy of thinking about a one-size-fits-all solution to the teacher pipeline squeeze in this state.

Filling teacher vacancies is often difficult in rural areas for a host of reasons — lower supplements, fewer cultural amenities, widespread poverty — but for years, teacher recruitment and retention strategies were typically homogenous across the state, blind to geography.

“It’s very hard for the rural areas to keep young teachers,” says Winner, the former state legislator who studied the teacher pipeline during her time leading the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation. “They may start out in a district that’s 100 miles from Raleigh or Durham or Charlotte. But when they can, they’ll move in.”

Chapman has watched this happen, in the aggregate, across North Carolina for years. “You might imagine how you might watch a football play, you know, with the X’s and O’s moving around,” she says.

After the most recent recession, large, urban school districts such as Charlotte-Mecklenburg, started recruiting teachers from rural parts of the state. Two years ago, then-CMS Superintendent Ann Clark said she was “deeply conflicted” about using Charlotte’s sports teams, cultural amenities, and quality of life to “steal teachers away” from the state’s rural school districts in order to fill vacancies in her own district.

Large districts face a different kind of staffing struggle: Teachers moving from high poverty schools where conditions can be tough, to affluent schools in suburban areas that are perceived to be easier assignments. “Of course we can’t tie them down,” Winner says. “If you say they can’t transfer, then they leave. You can incent people to stay, but you can’t force them to stay.”

This is why the distribution of teachers — and not just the supply — matters in North Carolina. The state’s colleges could be producing enough math teachers, for example, to fill the number of vacancies that exist. But if those teachers concentrate in urban school districts, suddenly rural communities have a shortage of math teachers because the qualified teachers aren’t evenly distributed across the state.

Van Dempsey, who leads the UNC Wilmington College of Education, says the school has strong partnerships with rural school districts in eastern North Carolina. They try to work together on “grow your own” models of teacher recruitment and preparation — in other words, ways to convince people to return to their hometowns and teach.

“People are predisposed to want to live in particular areas,” Dempsey says. “How do we facilitate people who want to be teachers seeing those options — going to a place like Bertie County or Halifax County or Lenior?”

None of the people interviewed for this series could comfortably give an example of a school district in North Carolina that is successfully combatting its staffing shortages in a way that could be applicable to other districts across the state. “We have different conditions here in North Carolina,” Stoops says. “We have a different dynamic with our community, with our urban and suburban cores, our rural areas. It’s tough to generalize given the size of North Carolina, the different conditions that each of our regions have, the different challenges the schools in those areas face.”

Farrelly says discussions about the teacher pipeline are riddles for politicians and bureaucrats and academics to ponder. He is reminded of that every day as he sees classrooms with effective teachers and happy students. And he is reminded of it every year when he has to replace dozens of teachers who leave for myriad reasons.

“I tell my staff it’s not for everyone, but certainly teachers make the difference. They impact student lives every day,” he says. “We feel like we’re open to taking some chances for the right reasons.”

North Carolina Insight Education Vol. 25 No. 1