Improvement for North Carolina attainment numbers will require continued focus and support at the local, state, and federal levels in the coming years.

It is not surprising that all three higher educational systems in North Carolina—The University of North Carolina (UNC), the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS), and the North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities (NCICU)—have each made increased educational attainment a priority. There are numerous established programs, many of which are collaborative across systems, with the objective to raise overall numbers of the population with a credential beyond high school. Outlined in this chapter are some of the strategies being carried out across North Carolina’s systems of higher education. Improvement for North Carolina attainment numbers will require continued focus and support at the local, state, and federal levels in the coming years.

The University of North Carolina System

In 2013, UNC published a plan detailing its strategic directions for 2013-2018 entitled, “Our Time, Our Future.” This compact with the state identified the following five, broad-based goals, the first of which deals specifically with attainment:

In 2013, UNC published a plan detailing its strategic directions for 2013-2018 entitled, “Our Time, Our Future.” This compact with the state identified the following five, broad-based goals, the first of which deals specifically with attainment:

- Set degree attainment goals responsive to state needs

- Strengthen academic quality;

- Serve the people of North Carolina;

- Maximize efficiencies; and

- Ensure an accessible and financially stable university.1

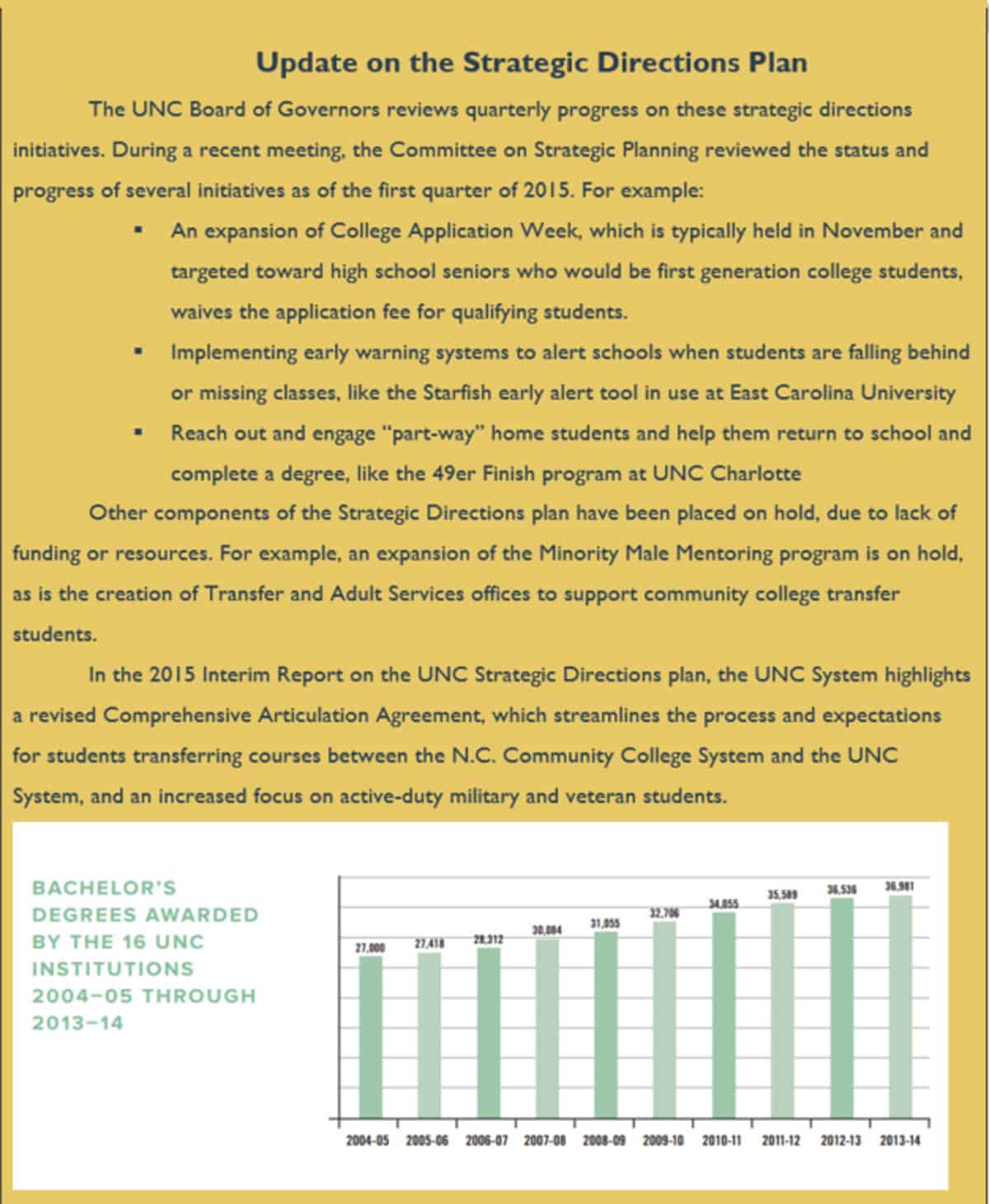

By setting its first goal, UNC has pledged to help the state reach a bachelor’s degree or higher attainment level of 32 percent by 2018 (the current rate is close to 27 percent). In addition, UNC is committed to ensuring that North Carolina becomes one of the top ten most educated states by 2025 by increasing the percentage of the population that holds a bachelor’s degree or higher to 37 percent.2

The compact outlines several strategies for increasing attainment levels and achieving the first goal. These strategies assume that they will be carried out in a way that takes into account the state’s varied demographics and also the need for flexibility in order to adapt to changing circumstances over time. The compact also assumes that UNC alone cannot account for reaching the proposed attainment levels and, therefore, the effort must be in close collaboration with both the community colleges and private institutions.

In order to increase attainment levels, UNC will target the following specific demographic groups:

- High school graduates

- Community college graduates and transfers

- “Part-way home” students (individuals with some college credit, but no degree)

- Military-affiliated students/veterans

- Adult and distance learners3

The number of graduates will increase not simply through increasing enrollment, but also by improving retention and graduation rates among current and future students.

The UNC system, through its compact, has outlined a variety of strategies and corresponding action steps to increase overall attainment rates. Because of the nature of tracking attainment, it will inevitably take two to six years to move students through degree completion. Therefore, degree attainment rates will not show immediate improvement but should instead rise steadily over time.

A Focus on Military-Affiliated Students

The development of a system-wide recruiting strategy for the military-affiliated student population, which includes custom academic pathways, academic success contracts, targeted materials, and other best practices is currently underway. This includes the establishment of system-level support and logistical assistance for UNC institutions that are recruiting, enrolling, and graduating military-affiliated students.4

The development of a system-wide recruiting strategy for the military-affiliated student population, which includes custom academic pathways, academic success contracts, targeted materials, and other best practices is currently underway. This includes the establishment of system-level support and logistical assistance for UNC institutions that are recruiting, enrolling, and graduating military-affiliated students.4

A process by which admission and transfer policies are streamlined for consistency in determining residency and value of credit is also nearing completion. Incentives for faculty to develop flexible online courses that can be taken outside the normal semester schedule to meet degree requirements is on-going.5

The North Carolina Community College System

SuccessNC

SuccessNC, a multi-year strategic planning process, began in October 2009 with the goal of increasing the access and success of students and improving the performance of programs across the N.C. Community College System (NCCCS).6 Through a listening tour of each community college campus across North Carolina, best practices as well as barriers to student success were identified. Following these conversations, a set of initiatives was developed that focused primarily on increasing student success rates from the first point of contact with a community college through program completion. Today, the refined mission of SuccessNC, after years of development, is to increase graduation rates of community college students in order to provide more North Carolina families with the ability to earn a sufficient and reliable income.7

The primary goal of SuccessNC has three components:

- To Improve Access so that a greater number of students can successfully enroll and complete their desired course of study.

- To Enhance Quality by providing programs and courses that not only meet the changing demands of the workforce, but that guarantee the rigor to allow graduates to excel in the workforce or in further higher education pursuits.

- To Increase Success by getting more students through to completion so that they graduate with a credential that will ensure their ability to find steady employment as well as provide the foundation for continued skill development over a lifetime.8

Completion by Design

North Carolina and the NCCCS was one of only four states selected in 2011 to participate in the pilot program of Completion by Design, which is designed by and funded through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The SuccessNC framework is modeled after the Completion by Design program, with the primary goal of implementing innovative strategies to increase student completion. A leadership group was formed to determine policy changes that would move the state’s 58 community colleges toward that goal. These policy priorities were organized into four main categories:

1.) Legislative,

2.) K-12 and higher education alignment,

3.) State Board of Community Colleges, and

4.) College policy levers.9

While the leadership group determined numerous innovative strategies, the following three were identified as having the highest priority:

- Revise the State Board of Community Colleges’ student placement and developmental pre-requisite policies: This change would allow students’ qualifications for admission to be determined by more qualitative research rather than a single test score. It would also allow students to enroll in courses even if they placed “near college-ready” so they can take both the developmental course and the supplemental course simultaneously. This would remove barriers to degree attainment by improving the quality of study the student receives and reducing the time to credential.

- Revise the NCCCS curriculum standards to facilitate highly structured programs of study at the college level: By clustering similar programs and stacking credential options to allow for multiple points of entry and exit, this change would create flexibility and increase opportunities for students as they pursue a course of study.

- Revise the Comprehensive Articulation Agreement between the North Carolina Community College System and The University of North Carolina’s 16 constituent college institutions to develop structured pathways to majors and reduce elective options: The revision would provide a more seamless transition between courses of study at community colleges and at UNC campuses across the state would promote attainment through course of study alignment and easier credit transfer.10

Comprehensive Articulation Agreement

The North Carolina Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (CAA), a statewide agreement facilitating the transfer of credits between NCCCS and UNC campuses, was recently revised to allow for a more streamlined and transparent transition of students from one system to the other on the path toward degree completion. A community college student may choose to earn an Associate’s degree in Arts or in Sciences, which will afford him or her junior status upon transfer to a four-year institution to earn a bachelor’s degree. The existence of the CAA, as approved by both the UNC Board of Governors and the NC State Board of Community Colleges, ensures the transfer of any community college student who has successfully earned an Associate’s degree in Arts or in Sciences. Further, the student is protected in that he or she may file a grievance if it is believed that the CAA has not been upheld.11

Reverse Credit Transfer Program

The Reverse Credit Transfer Program is a partnership between fifteen states, including North Carolina, and five major education foundations. The program allows community college students who transfer to four-year universities before earning an Associate’s degree to send their earned credits back to the community college they previously attended and obtain the degree they would have been awarded. There is no additional cost to the student. For many, this is merely a formality and requires no additional coursework since the student has already accumulated the credits to earn the Associate’s degree.

Receiving the Associate’s degree while at a four-year college can have several benefits. For example, it will: 1.) bolster future earning potential, 2.) strengthen psychological resolve to complete a Bachelor’s degree, and 3.) allow students to receive the full credentials they have earned. Furthermore, for the student who does not go on to complete a Bachelor’s degree, the Associate’s degree boosts their lifetime earning potential. Currently, the Reverse Credit Transfer Program is being piloted at eight UNC campuses and fifteen community colleges statewide. The pilot is on track to meet its goal for reverse transfer Associate’s degrees awarded and, therefore, the program is expected to begin scaling up across both systems.12

Career and College Promise

The Career and College Promise initiative is an innovative solution for plugging the educational pipeline between high school and college by providing overlapping credit accumulation. The program works by allowing high school students to earn credits while still in high school (at no cost) that count toward a post-secondary degree. High school juniors and seniors are eligible to participate; in some participating schools, high school freshman and sophomores may enroll to receive a high school degree and an Associate’s degree in a reduced timeframe. The initiative gives students a head start toward the degree of their choice in three ways:

- College credit is completely transferrable to all UNC campuses and many of North Carolina’s private institutions.

- A credential, certificate, or diploma in a technical career can be earned.

- A high school diploma and two years of college credit in four to five years through innovative cooperative high schools (limited availability) can be earned.13

Minority Male Mentoring Program

The goal of the Minority Male Mentoring Program (3MP), a student coaching program, is to increase the college completion rates and, in turn, the professional opportunities available specifically for minority males enrolled at North Carolina community colleges. Started in 2003 and supported by the N.C. General Assembly and federal grants through the U.S. Department of Education, 3MP has received sub-grants to operate in 46 of the 58 community colleges statewide. The focus of the 3MP is consistent: to complete required coursework, to return to school each semester and each year, to earn a degree, and/or to transfer to a four-year institution. Given the program’s success, the aspiration is to expand its presence to all 58 community colleges and to continue to provide innovative pathways to increased educational attainment for minority males, particularly given that they traditionally have the lowest levels of completion among any demographic group.14

North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities

College Access Challenge Grant

College Access Challenge Grant

The College Access Challenge Grant (CACG) is a federal grant through the U.S. Department of Education used to support programs that increase college enrollment and completion, particularly among underrepresented groups. The population of each state determines the amount of funds received through the grant. Each state has relative autonomy in determining how they use the funds to support programs and scholarships. Our state’s private colleges and universities rely on this funding stream to provide programs that increase the success rates of low-income, first generation, adult and/or minority students on their campuses.15

During the 2010-2011 grant year, a handful of private colleges implemented programs using CACG funds that enjoyed a good deal of success. For example, at Guilford College, the Getting Prepared for Success (GPS) program was established to prepare both traditional age (18) and non-traditional age (adult) first generation or at-risk students for success in college. GPS offered a summer retreat that focused on study skills and strategies. In addition to creating a supportive community, GPS provided participants with the background necessary to navigate the college experience successfully. Data show that, although the sample size was relatively small (only 18 participants), academic performance among participants of GPS was greater than performance of non-participants, particularly among adult learners. GPS was offered the following year and increased in participation by 50 percent. Success rates among participants continued to climb, establishing GPS as an effective effort to increase persistence and completion rates among underrepresented groups.16

During the 2011-2012 grant cycle, the number of private colleges offering programs for underrepresented groups grew and saw important successes in accomplishing their missions. For example, Chowan University established the “1st Flight” program that engaged thirteen at-risk students in a 5-day residential program to prepare students for the challenges of college life. The program was highly successful, as 100 percent of participants enrolled for the following fall semester and the cumulative GPA of participants was higher than that of the control group.17

At Duke University, “The IG Network: a Program for First Generation College Students” was established to ease the transition to college life for first generation students by helping them build and cultivate meaningful relationships with faculty. Consistently, 98 percent of participants indicated that the program helped them navigate the college environment successfully.18

Several private colleges, including Methodist University and Shaw University, established Summer Bridge Programs with the express intent of preparing at-risk students for college life. The programs at these two campuses produced data indicating a positive impact on student participants, including increased levels of academic achievement, persistence and re-enrollment.19

Introduction Part One Part Two Part Three Part Four

Promising Programs Statewide: Fayetteville State University

Promising Programs Statewide: Elizabeth City State University

Promising Programs Statewide: College of The Albemarle

Promising Programs Statewide: Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College

Promising Programs Statewide: Bladen Community College

Snapshot: Veteran and Military Students

Promising Programs Statewide: UNC-Greensboro

Promising Programs Statewide: Bennett College

Promising Programs Statewide: University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Promising Programs Statewide: University of North Carolina at Pembroke

Michelle Goryn is a writer and public policy consultant in Raleigh, NC.

Paige C. Worsham is Senior Policy Counsel with the North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research and conducted the interviews and convenings for this project.

The N.C. Center for Public Policy Research is grateful to numerous, generous supporters. Major funding for this project is provided by the Lumina Foundation for Education, with additional funding from the James G. Hanes Memorial Fund, and the Hillsdale Fund.

- UNC Strategic Directions 2013-2018: “Our Time, Our Future,” p. 4 ↩

- UNC Strategic Directions 2013-2018: “Our Time, Our Future,” p. 13 ↩

- UNC Strategic Directions 2013-2018: “Our Time, Our Future,” p. 19 ↩

- “Our Time, Our Future,” UNC General Administration, Interim Report 2015, http://www.northcarolina.edu/sites/default/files/documents/14-3741-gad-university_strategic_plan.pdf. ↩

- The University of North Carolina Partnership for National Security, UNC General Administration, http://uncserves.northcarolina.edu/. ↩

- “SuccessNC Final Report,” NC Community College System, 2013, http://www.successnc.org/sites/default/files/SuccessNC%20Report.pdf. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Completion by Design,” N.C. Community College System, http://www.successnc.org/initiatives/completion-design. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Comprehensive Articulation Agreement,” N.C. Community College System, http://son2.nccommunitycolleges.edu/programs/comprehensive_a_a.htm. ↩

- “Reverse Transfer Credit,” N.C. Community College System, http://www.successnc.org/initiatives/comprehensive-articulation-agreement-revision-reverse-transfer-credit-0. ↩

- “Career and College Promise,” N.C. Community College System, http://www.successnc.org/initiatives/career-college-promise-0. ↩

- “Minority Male Mentoring Program,” N.C. Community College System, http://www.successnc.org/initiatives/minority-male-mentoring-program. ↩

- “College Access Challenge Grant,” N.C. Independent Colleges and Universities, http://www.ncicu.org/student_collegeaccess.html. ↩

- Ibid. Follow program and accomplishments links. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩