Our approach to higher education must adapt in order to meet the needs of students in the face of a changing job market.

As outlined in the first chapter, our state’s demographics are in a constant state of change. Minority populations are growing and baby boomers are retiring en masse, all at a time when our economy is shifting to one based on high-skill jobs that require a credential beyond high school. Our approach to higher education must adapt in order to meet the needs of students in the face of a changing job market. The higher education structure must establish new, and retool existing, mechanisms to ensure that enrolled students graduate on time and with a relevant degree. The structure must also work to enroll and graduate more students not currently in the system.

A particular focus must be placed on at-risk populations whose attainment rates tend to suffer more than their counterparts.

This can be due to many underlying factors; for example, geography, socioeconomic status, access to broadband, and family and community culture. These are certainly barriers, but they are not insurmountable. When an entire demographic group is consistently underrepresented in our educational system and, subsequently, in the high-skilled workforce, this can have far-reaching, negative economic consequences such as high unemployment rates, increased spending on social service programs, and a decrease in state and local revenues. Numerous programs statewide have seen a great deal of success in increasing attainment for at-risk students.

The previous chapter highlighted several initiatives geared toward increasing educational attainment across all three higher education systems in our state, many of which focus specifically on engaging minority and nontraditional students. A sound education is the ultimate equalizer. However, the most disadvantaged groups in our state face the greatest challenges to receiving a quality education capable of providing them with a lifetime of upward mobility.

In this chapter, educational institutions targeting and assisting underserved populations such as African Americans, Hispanic students, first-generation college students, nontraditional students and students from rural counties will be highlighted. These institutions are doing so in collaborative ways, often using a mix of mechanisms including distance education and the creation of a comprehensive support network to give students the best chance of success. This chapter is dedicated to detailing more of these critical programs and the successes and challenges they have faced as they work to increase attainment levels among some of our state’s most underserved populations. Many common elements can be identified among these programs, which, in turn, will serve to inform the replication and scaling of the most promising programs statewide and beyond.

Groups Constituting the At-Risk Student Population

Nationally, the average four-year college graduation rate for African American students is almost 20 percentage points below that of white students. The graduation rate for African American students from private colleges is 55 percent while the rate for white students is 73 percent. The graduation rates in public universities show a similarly wide gap, with 43 percent of African Americans graduating in six years compared to 60 percent of white students.1 While the achievement gap and graduation gap is closing for minority students, African American students often graduate high school with a weaker performance than their white peers.2 So it can be argued that the challenge lies in improving academic performance for minority students within secondary education. However, research has shown that strategies used in higher education to enroll, retain, and graduate minority students can have a significant impact on improving their attainment levels, despite the disparity in earlier educational experiences.3

Similarly, Hispanic students, on average, have significantly lower graduation rates than white students. This is due, in part, to lower enrollment numbers, but also to the lack of a tailored support network within higher education to ensure successful degree completion. This is evidenced by the fact that less than half of Hispanics who enroll in college graduate within six years, compared to 60 percent of their white peers.4 Hispanics are expected to comprise one-third of the workforce in the United States by the year 2050. However, they are currently the least academically prepared to succeed in the changing economy. Only 13 percent of Hispanics have earned a bachelor’s degree, compared to 39 percent of whites and 21 percent of African Americans.5 While private colleges tend to graduate higher proportions of Hispanic students (65.7 percent compared to 47.6 percent at public institutions), most Hispanic students, about 80 percent, attend public universities where 60 percent graduate less than half of enrolled Hispanic students within six years.6

In 2012, about 39 percent of American Indian students who enrolled in a four-year institution graduated (compared to about 60 percent of white students).7 It is often more likely for American Indian students to be first-generation students. In 2011, about 19 percent of young adult American Indians had a parent with a bachelor’s degree, compared to about 48 percent of white young adults.8 In addition, American Indian students tend to come from low-income families and from rural communities, both of which present significant barriers to access and success in higher educational pursuits.

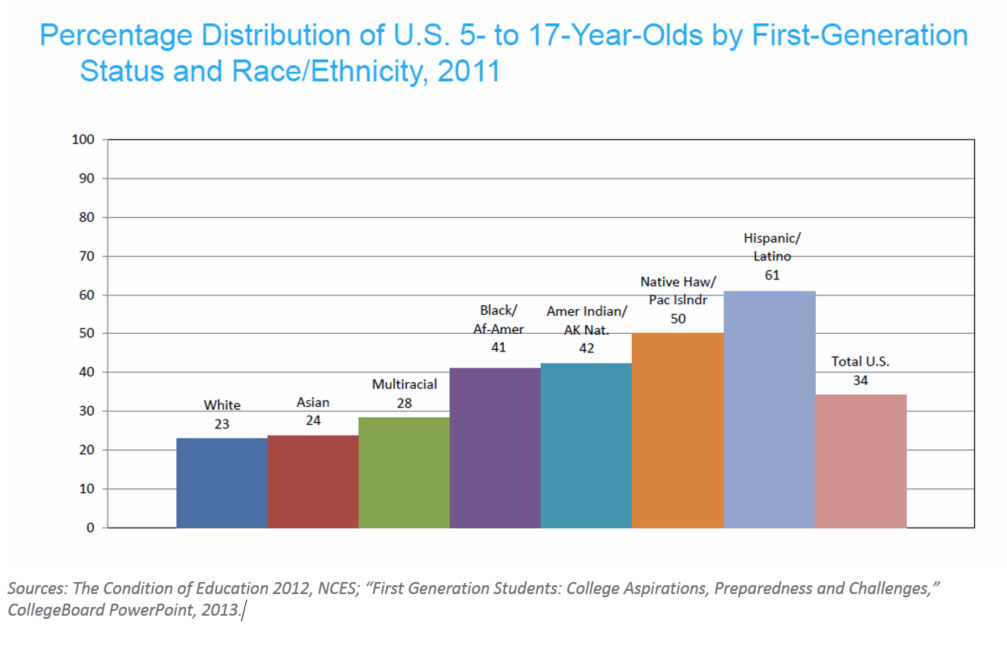

First-generation college students are significantly underrepresented among the college student population and even more so among those who have earned a degree. This is due in large part to the fact that first-generation students are less likely to perform well academically and persist throughout the educational pipeline. Of all non-first-generation students graduating from high school, 82 percent enroll in college, compared to 54 percent of students whose parents had only completed high school and only 36 percent of students with parents holding less than a high school diploma.9 In terms of persistence, first-generation students are less likely to be enrolled continuously and earn a degree at their initial post-secondary institution than students whose parents had completed college.10 First-generation students are more likely to require remedial coursework, delay entry into college and stop out before completion, making them among the most critically high-risk student group. Furthermore, traditionally underserved minority groups make up the overwhelming majority of first-generation students.

Adult learners, also referred to as nontraditional students, are constituting an increasingly large percentage of the college student population. It is estimated that roughly half of the student population enrolled in colleges and universities nationwide is over 25 years old, which prompts the question of whether these students are, in fact, more traditional than their name implies.11 According to the National Center for Education Statistics, students over age 24 have traditionally been defined as nontraditional. In addition, they must meet one of seven criteria: 1.) delayed enrollment, 2.) having dependents, 3.) being a single parent, 4.) being employed full-time, 5.) being financially independent, 6.) attending part-time, or 7.) not having a traditional high school diploma.12 This encompasses a large cohort of the total student population. The overarching focus in providing educational opportunities for nontraditional students is providing tailored support and flexibility to address the varied challenges they might face as they balance work, family, and academic responsibilities.

Many underserved students from different demographic groups live in rural areas. In fact, many rural towns in the South and Southwest regions of the United States have high numbers of low-income, minority residents. Coming from rural areas can present additional hurdles to degree completion. Only 17 percent of adults (25 years old or older) from rural areas have earned a college degree, which is about half the percentage of adults from urban areas.13 Furthermore, only 31 percent of rural college-age adults (age 18-24) were enrolled in higher education in 2009, compared to an average of 44 percent in urban and suburban areas.14

This is particularly troubling given that roughly a quarter of all public school children are from rural areas.15

This means that the educational pipeline is breaking down at much higher rates beyond city limits. This is the case for a variety of reasons For example, the expectation that students will attend a higher education institution is typically not a cultural norm in rural areas, residents are less likely to live near an institution, and students are less likely to have family members who attended college.16 With rural educational resources lacking, distance education is held up as a realistic means for increasing educational attainment in rural areas. However, access to reliable high speed internet remains a significant impediment to a sound education in rural communities. Certainly, increasing overall attainment levels cannot happen without increasing access to education in rural areas.

If effective support programs are put in place, graduation gaps among students from different at-risk groups are not inevitable. One student can fall into several different at-risk groups, so many of the successful programs in place target and support a host of underrepresented groups. There are numerous institutions—public and private universities and community colleges–that have very small graduation gaps among at-risk groups. Some excellent examples exist here in North Carolina. Next, we will highlight some of those institutions and attempt to extrapolate some important common elements found among these strategies in the hopes of scaling or replicating these efforts statewide.

Introduction Part One Part Two Part Three

Promising Programs Statewide: Fayetteville State University

Promising Programs Statewide: Elizabeth City State University

Promising Programs Statewide: College of The Albemarle

Promising Programs Statewide: Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College

Promising Programs Statewide: Bladen Community College

Snapshot: Veteran and Military Students

Promising Programs Statewide: UNC-Greensboro

Promising Programs Statewide: Bennett College

Promising Programs Statewide: University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Promising Programs Statewide: University of North Carolina at Pembroke

Michelle Goryn is a writer and public policy consultant in Raleigh, NC.

Paige C. Worsham is Senior Policy Counsel with the North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research and conducted the interviews and convenings for this project.

The N.C. Center for Public Policy Research is grateful to numerous, generous supporters. Major funding for this project is provided by the Lumina Foundation for Education, with additional funding from the James G. Hanes Memorial Fund, and the Hillsdale Fund.

- Mamie Lynch and Jennifer Engle, “Big Gaps, Small Gaps: Some Colleges and Universities Do Better Than Others in Graduating African-American Students,” The Education Trust, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED511866.pdf ↩

- “The State of Education for African American Students,” The Education Trust, June 2014, http://edtrust.org/resource/the-state-of-education-for-african-american-students/. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- National Indian Education Association, http://www.niea.org/Research/Statistics.aspx#HigherEd. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “First Generation Students: College Aspirations, Preparedness and Challenges,” CollegeBoard PowerPoint, 2013, https://research.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/publications/2013/8/presentation-apac-2013-first-generation-college-aspirations-preparedness-challenges.pdf. ↩

- Bridging the Gap: Academic Preparation and Postsecondary Success of First-Generation Students, National Center for Education Statistics, 2001, nces.ed.gov/pubs2001/2001153.pdf. ↩

- Success for Adult Students, Stephen G. Pelleter, American Association of State Colleges and Universities, 2010, www.aascu.org/uploadedFiles/AASCU/Content/Root/MediaAndPublications/PublicPurposeMagazines/Issue/10fall_adultstudents.pdf. ↩

- “Definitions and Data,” National Center for Education Statistics, http://nces.ed.gov/pubs/web/97578e.asp. ↩

- Sarah Beasley and Neal Holly, “To Improve Completion, Remember the Countryside,” The Chronicle of Higher Education; May 13, 2013, http://chronicle.com/article/To-Improve-Completion/139183/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩