Education can and must assume the role as the ultimate equalizer, in addition to its role as an economic engine.

Over the past few decades, post-secondary education and training have become increasingly crucial to the American economy. In 1973, workers with a post-secondary education held only 28 percent of jobs; by comparison, they held 59 percent of jobs in 2010 and will hold 65 percent of jobs in 2020. 1 At the current rate of production, the United States will fall short by 5 million workers with post-secondary education by 2020. 2 While opinions vary on how to increase educational attainment, the overwhelming agreement is that more workers than ever before will require some post-secondary credential to ensure our economic vitality into the future.

There is something of a “chicken and egg” phenomenon happening in terms of the link between educational attainment and economic strength.

The exponential growth of jobs requiring post-secondary credentials has created a lag effect in the workforce. Changing policies and practices within education that will get more students into the pipeline at any stage have traditionally been a slower process and, as a result, the production of a highly educated citizenry to effectively compete for these jobs has not kept pace with demand. Not surprisingly, those who suffer the most because of this challenge tend to be either low-income, minorities, or from more rural areas, if not all three. Addressing the need to increase educational attainment will not only boost our national and state economy but, if a particular focus is placed on traditionally disadvantaged groups, this effort will begin to address some of the social inequities that persist in society. Education can and must assume the role as the ultimate equalizer, in addition to its role as an economic engine.

There is something of a “chicken and egg” phenomenon happening in terms of the link between educational attainment and economic strength. Not only will highly educated people be better prepared to compete for high-paying, high-skill jobs, but post-secondary education and training for the workforce is key to creating and attracting high-paying and high-skill jobs. Companies tend to relocate or open new locations in areas where there is a highly trained workforce from which they can easily pull to meet their needs. In turn, companies with a skilled labor force tend to grow and expand, creating new jobs to be filled. This trend is part of the reason why areas with a highly trained workforce tend to have a stronger economy, a higher quality of life, and are less impacted by economic volatility like recessions.

Over the course of many years, we have seen our economy change. Once powered by low-skill, low-wage jobs—jobs held by those with a high school diploma or less that could provide a secure spot in the middle class—our economy has seen a sharp shift to a knowledge and service base. This trend has had a profound impact on the value we place on education. The link between education and a thriving economy is now more apparent and crucial than ever in our history. The fastest growing sectors with the highest predicted job growth will require increasingly higher levels of educational attainment to fill these jobs. Recent data show that education, healthcare and professional and business services will grow fastest, with over 80 percent of workers requiring post-secondary education and training. 3 This trend was exacerbated by the recent recession when the economy lost 5.6 million jobs for Americans with a high school diploma or less. What is especially noteworthy is that while jobs in every other educational category fell, jobs for those with a bachelor’s degree actually increased during the recession, albeit slowly, by 187,000. 4

It is estimated that 65 percent of all jobs in the economy by the year 2020 will require at least some post-secondary education. 5 That is only five years away. This percentage can be further broken down to show that 35 percent of jobs in 2020 will require at least a bachelor’s degree, 30 percent will require some college or at least an associate’s degree, and 36 percent will not require any credential beyond high school. 6 Not only will more jobs be available for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, but obtaining a post-secondary credential ensures higher earnings over a lifetime with few exceptions. In fact, the earnings gap over a lifetime between individuals with a post-secondary degree and those without continues to grow. In 2002, a bachelor’s degree-holder could expect to earn 75 percent more over a lifetime than someone with only a high school diploma. Today, that divide is closer 84 percent/ 7

In North Carolina, the trend is no different. As our state’s economy has shifted from traditional manufacturing to a knowledge-based economy, it is expected that by 2018, 59 percent of jobs in the state will require education beyond high school. 8 According to 2013 Census data, “39.7 percent of North Carolina’s 5.2 million working-age adults (25-64 year-olds) hold a two- or four-year college degree.” 9 However, our state’s college attainment rate is increasing, albeit slowly. According to the Lumina Foundation, one indicator for future college attainment rates can be found by looking at rates among young adults (between the ages of 25 and 34). Census data in 2013 put the North Carolina attainment rate for young adults at 40.1 percent, about the same as the entire adult population and below the national rate of 41.6 percent. 10

Dr. Jason Desousa, Fayetteville State University’s Assistant Vice Chancellor for Student Retention (pictured above) talks with Center Senior Policy Counsel Paige C. Worsham about minority male mentoring programs in this clip.

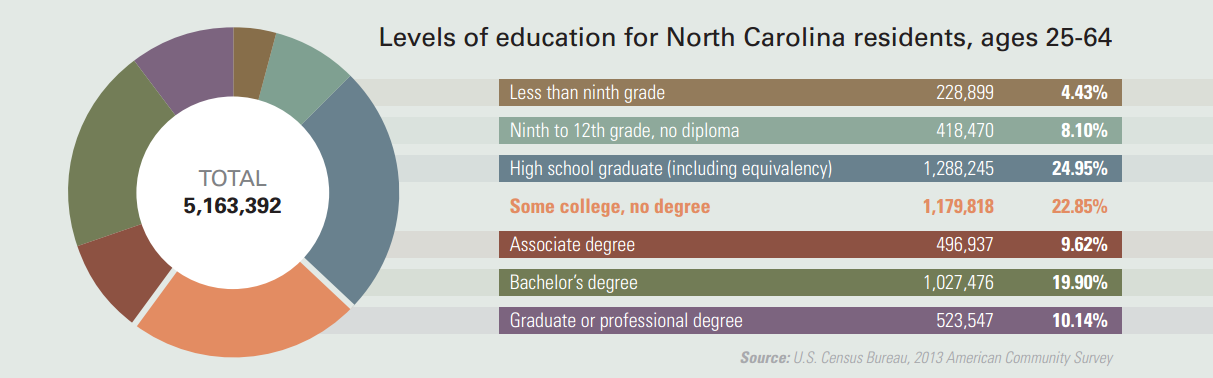

Education levels among North Carolinians vary widely, particularly when examining degrees and demographic groups. The largest percentage of adults (ages 25-64) in North Carolina hold at least a high school diploma or the equivalent at 24.95 percent of the population. The next largest percentage of adult North Carolinians have some college but no degree (22.85 percent of the population). This number could reflect a breakdown in the education pipeline that must be fixed if attainment rates are to increase in the state. Other leaks in the pipeline can be seen in the percentage of students dropping out by ninth grade (4.43 percent) and those dropping out in high school before receiving a diploma (8.10 percent). 11

Considerable statewide demographic change offers an important qualification that requires careful consideration when addressing the goal of increased attainment. The 2010 Census shows that North Carolina’s Hispanic population has doubled, our African American population has grown as well, and our state has become increasingly urbanized. In addition, we are experiencing a growing aging population (the Baby Boomers), many of whom entered the workforce when a high school degree was sufficient to earn a living wage. They now find themselves remaining in the workforce for financial reasons, but many are not adequately trained for the jobs of the changing economy.

Ensuring that all students graduate from college with relevant coursework or obtain an applicable credential is the only way North Carolina will develop a workforce that will meet the needs of the future job market, both in numbers and skills.

All of these demographic trends will have an impact on the best methods to increase college attainment rates among North Carolinians. Because our state is experiencing such extreme demographic changes, particularly given the rapidly growing minority population, it is without question that attainment rates will not reach necessary numbers without a particular focus on Hispanic and African American students. In fact, there simply are not enough qualified workers for the high-skill jobs of today, much less those jobs expected to exist in our economy in the decades to come. Ensuring that all students graduate from college with relevant coursework or obtain an applicable credential is the only way North Carolina will develop a workforce that will meet the needs of the future job market, both in numbers and skills. Without an educated minority population, our state will fall short of filling the number of expected high-skill jobs and, ultimately, this could mean significant and long-term economic instability.

According to the UNC System’s Compact with North Carolina, “Our Time, Our Future,” 26 percent of the state’s population holds a bachelor’s degree. The UNC system has set as its system-wide goal a 32 percent bachelor’s degree attainment rate by 2018 and 37 percent by 2025, putting North Carolina in the top ten best educated states in the country. 12 The North Carolina Community College System also has a broad effort in place to increase the percentage of students who transfer, complete credentials, or remain continuously enrolled, from a six-year baseline of 45 percent for the fall 2004 cohort to a six-year success rate of 59 percent for the fall 2014 cohort. Doing so will double the number of credential completers by 2020. 13 Given that the North Carolina Community College System increased statewide enrollment by 44 percent from 2000-2009, 14 they are on their way to achieving this goal.

The following installments will examine strategies to increase attainment rates among specific groups of students who are most vulnerable to falling short of their educational promise. This includes first-generation college students, students from rural parts of the state, and minority students. Without educational participation and achievement from North Carolina’s entire population, our state risks falling behind in our ability to compete in the global economy.

Introduction Part One Part Two Part Three Part Four

Promising Programs Statewide: Fayetteville State University

Promising Programs Statewide: Elizabeth City State University

Promising Programs Statewide: College of The Albemarle

Promising Programs Statewide: Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College

Promising Programs Statewide: Bladen Community College

Snapshot: Veteran and Military Students

Promising Programs Statewide: UNC-Greensboro

Promising Programs Statewide: Bennett College

Promising Programs Statewide: University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Promising Programs Statewide: University of North Carolina at Pembroke

Michelle Goryn is a writer and public policy consultant in Raleigh, NC.

Paige C. Worsham is Senior Policy Counsel with the North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research and conducted the interviews and convenings for this project.

The N.C. Center for Public Policy Research is grateful to numerous, generous supporters. Major funding for this project is provided by the Lumina Foundation for Education, with additional funding from the James G. Hanes Memorial Fund, and the Hillsdale Fund.

- “Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements through 2020,” June 2010, Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, Executive Summary,http://www9.georgetown.edu/grad/gppi/hpi/cew/pdfs/Recovery2020.ES.Web.pdf ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “A Stronger Nation through Higher Education,” Lumina Foundation Annual Report, 2013, http://www.issuelab.org/resource/stronger_nation_through_higher_education_visualizing_data_to_help_us_achieve_a_big_goal_for_college_attainment_a ↩

- “Recovery: Job Growth and Education Requirements through 2020,” June 2010, Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, Executive Summary, http://www9.georgetown.edu/grad/gppi/hpi/cew/pdfs/Recovery2020.ES.Web.pdf ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime earnings,” August 2011, Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, Executive Summary, http://www9.georgetown.edu/grad/gppi/hpi/cew/pdfs/collegepayoff-summary.pdf ↩

- “The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime earnings,” August 2011, Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, Executive Summary, http://www9.georgetown.edu/grad/gppi/hpi/cew/pdfs/collegepayoff-summary.pdf ↩

- “A Stronger Nation through Higher Education,” Lumina Foundation Annual Report, 2015, http://strongernation.luminafoundation.org/report/#north-carolina ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Our Time, Our Future,” The UNC Compact with North Carolina, Strategic Directions Initiative, 2013-2018, https://www.northcarolina.edu/?q=content/our-time-our-future ↩

- NCCCS, SuccessNC Initiative, http://www.successnc.org/guiding-goals. ↩

- “Education,” Institute for Emerging Issues http://iei.ncsu.edu/iei-issue-areas/education/. ↩