The election results are clear. People across North Carolina feel othered across any number of dividing lines. And we need them to feel tethered to a state they are proud to call home. Lesson learned.

In the weeks leading up to the election, in speeches to groups like Teach for America’s Rural School Leaders Academy, I asked audiences to forget. Forget what you think you know about the election and our state. Forget the headlines. Forget the polls. Forget the campaign ads.

It is easier to understand the election if you forget first, and then think about what you know about North Carolina’s people, our communities, and the issues facing both — and more importantly, the differences emerging across our great state.

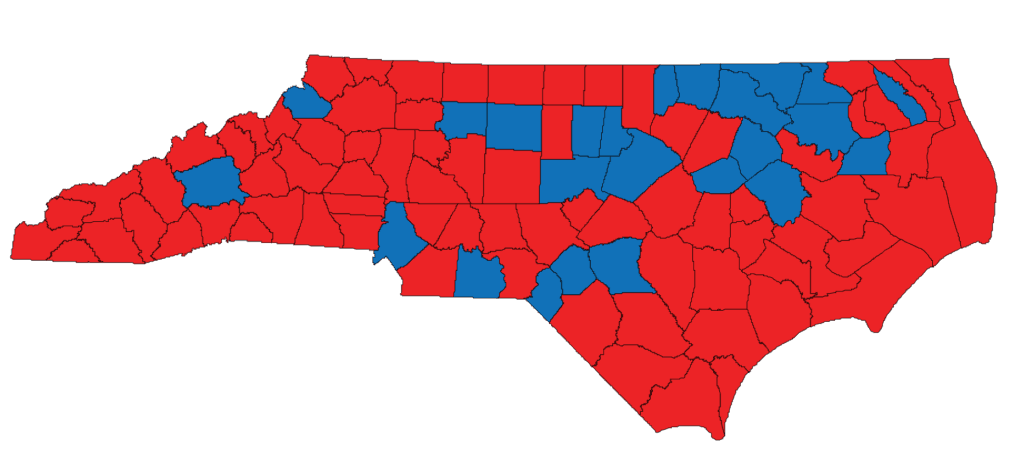

This is the map of the unofficial general election presidential results in 2016.

On election day, Rob Christensen with The News & Observer, based on an interview with Andrew Taylor, a political scientist at N.C. State, wrote, “Taylor said it’s unlikely that North Carolina will morph into either a strongly Democratic or Republican state in the foreseeable future, but will remain a strong purple.”

John Hood, the chair of the John Locke Foundation, has subdivided purple states into violet, fuchsia, magenta, and rose, putting North Carolina in the magenta category as a GOP-leaning state with some recent Democratic victories for president, U.S. Senate, governor, or legislative chambers. The nuance is important, he argues, encouraging those on the left and right to drill down and look at regional patterns.

In North Carolina, President-Elect Donald Trump won 76 of our 100 counties. In 23 counties, he won more than 70 percent of the vote: Alexander, Alleghany, Ashe, Avery, Caldwell, Camden, Carteret, Cherokee, Clay, Currituck, Davidson, Davie, Graham, Lincoln, McDowell, Mitchell, Randolph, Rutherford, Stanly, Stokes, Surry, Wilkes, and Yadkin. In two counties, he won more than 78 percent of the vote.

Most of these counties are west of our blue crescent running from Charlotte to Raleigh. Of the 24 counties Hillary Clinton won, she won only two with more than 70 percent of the vote — Durham and Orange.

Back in 1994, when Republicans won 92 of the 170 seats in the legislature, I asked whether the wins were reactionary — anti-Democrat, anti-tax, anti-big government; revolutionary — a changing of the guard from Democrats who governed for most of the 20th century to Republicans who were hoping to govern for much of the 21st century; or evolutionary — a single step towards becoming a competitive, two-party state. The elections in 2016 and 2020 will become an important part of our state’s story about the evolution of party politics.

The 2020 election will be another 10-year election, and the party that wins the majority will be able to draw the redistricting maps, build momentum, and raise lots of money.

Both parties are incented, based on these election results, to build cross-racial working class coalitions that focus on jobs. Increasingly, different regional strategies will be needed for politics, policy, and grantmaking across North Carolina.

The echo chamber

If you listened to the media, you expected a Clinton win. You believed Trump didn’t have a ground game. You thought that the Republican party would be the one recreating itself after the election.

Two business principles are at play in politics, policy, and the media nationally and in North Carolina — availability and confirmation bias. People base their perceptions on information that is easiest to come by — that’s availability. But availability is complicated by confirmation bias. People seek and consume information that confirms what they want to believe.

The decline in rural journalism — which often has its pulse on local trends — compounded the echo chamber effect.

Post election day, Republicans control the White House, the U.S. Senate, and the U.S. House for the first time since 1928.

So forget what you think you know.

A surprising election?

Instead of relying on polling, I have long thought a better predictor of the mood of voters and the outcome of elections is to just talk to people in different communities. Here are some takeaways from my travels during this election season.

As a nation, we are headed toward an event horizon in 2044 when minorities will collectively become the majority. Increasingly, poor, rural, White America is feeling othered. This trend screams off the pages of J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, a memoir about his journey from rural Appalachia to Yale Law School.

“It was Greater Appalachia’s political reorientation from Democrat to Republican that redefined American politics after Nixon,” Vance writes. “And it is in Greater Appalachia where the fortunes of working-class whites seem dimmest. From low social mobility to poverty to divorce and drug addiction, my home is a hub of misery.”

In the weeks leading up to the election, Trump/Pence signs were everywhere in the counties that voted red across North Carolina, begging the question: If Trump didn’t have a ground game, how did he get so many signs out so early? I always take note of how many homemade signs there are too.

As I traveled our most rural nooks and crannies, like Jake’s Mountain Road in Watauga County, I couldn’t help but wonder if the polling was capturing these Trump supporters or if they were off our political radar. Nate Silver told us the election would be unpredictable, and on election day gave Trump 29 percent odds of winning the electoral college.

Analysts thought the presidential election was about candidates and not issues. But for the people voting for Trump it was about one issue. Jobs.

Remember when now-U.S. Senator Thom Tillis wore and handed out wristbands that said, “Think JOBS,” in his statewide campaign to help Republicans win the state house in 2010.

We learn a couple of important lessons when we look at the way Tillis (who was not running in this election) and Lt. Governor Dan Forest campaign. They visit all 100 counties, making a point to talk to real people in schools and churches, not just influencers, and they pay attention to the issues their voters care most about.

Watching early voting and turnout trends will be important as we move toward 2020. Clinton won early voting in North Carolina, but Trump garnered 1,375,185 early votes compared to 1,153,723 in Mitt Romney’s bid in 2012. And, even though Clinton won the popular vote nationally, I am not convinced that concerts with rock stars are the best way to actually get out the vote.

Our magenta hue

In North Carolina on election day, there were 2,733,188 Democrats; 2,086,942 Republicans; 32,333 Libertarians; and 2,065,687 unaffiliated registered voters.

Democrats should win statewide races, but many of our voters have been splitting tickets for decades, voting comfortably in past elections for Republican Senator Jesse Helms and Democratic Governor Jim Hunt. We like to vote for incumbents and name recognition matters, but going forward we need to dig deeper to understand how North Carolina voters are splitting tickets.

Democrat Roy Cooper may hold on to his lead in the gubernatorial race, and Josh Stein, Beth Wood, and Elaine Marshall will sit on our Council of State as Attorney General, Auditor, and Secretary of State respectively. In a big win for Democrats, Mike Morgan won his nonpartisan race for a seat on the N.C. Supreme Court with 54 percent of the vote.

Deborah Ross’s U.S. Senate campaign took a page from the Tillis/Forest playbook visiting almost all of our 100 counties, and but for Trump’s win, that race almost certainly would have been closer.

First Vote NC

EdNC worked with First Vote NC, the Department of Public Instruction, and the NC Civic Education Consortium, to build a platform for high school students across the state to participate in a mock election.

Our next generation of voters also seems comfortable splitting tickets, with students choosing Hillary Clinton (D) for president, Richard Burr (R) for U.S. Senate, Roy Cooper (D) for Governor, Dan Forest (R) for Lt. Governor, Cherie Berry (R) for Commissioner of Labor, with Democrats picking up the other Council of State offices.

Governing

Governing requires a whole different skill set for politicians than campaigning, and from the White House to the school house, those just elected on both sides of the aisle have to figure out how to connect politics and policy to the lived realities of voters.

Vance, who grew up in the Rust Belt, writes:

“I want people to know what it feels like to nearly give up on yourself and why you might do it. I want people to understand what happens in the lives of the poor and the psychological impact that spiritual and material poverty has on their children. I want people to understand the American Dream as my family and I encountered it. I want people to understand how upward mobility really feels. And I want people to understand something I learned only recently: that for those of us lucky enough to live the American Dream, the demons of the life we left behind continue to chase us.”

Dominique Stone, a teacher in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, writes;

As a Black male educator, I feel the pain of my brothers and sisters who are living in fear, I know the pain of my Black male scholars whose future lies in the hands of those who have no clue what it is like to be Black in America, and I empathize with the pain of those who know what true freedom looks like but are stricken to the cycle of poverty.

We need leaders that will build an economy and a state that works for white rural voters and black urban voters and everyone in between.

The dividing lines that played so prominently in this election — race and ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, rich and poor, urban and rural, conservative and liberal — can’t be ignored or leaders will continue to see protests in our streets and our voting booths. Lives lived in fear or misery don’t usually serve as springboards to life times of opportunity. Othering just doesn’t work.

As Obama reminded the country the day after the election, we are Americans first.

And we are all North Carolinians.

Mebane Rash is the CEO of Education NC and the NC Center for Public Policy Research

Mebane Rash is the CEO of Education NC and the NC Center for Public Policy Research